"A Place to Stand" | Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Bill Kretzel, Ottawa, Canada | Date: 02.10.2011 |

"A Place to Stand" (0:18). Filmed in: 35mm, 4

perforations, 24 frames per second. Principal photography in:

Anamorphic and flat *).

Presented on: The curved screen in 70mm with 6-track magnetic stereo.

Aspect

ratio: 2,21:1. Country of origin: Canada. Production year: 1966/7.

World

Premiere: 28.04.1967, Ontario Pavilion, Expo 67, Montreal, Canada. German

premiere: 09.10.2011 "A Place to Stand" (0:18). Filmed in: 35mm, 4

perforations, 24 frames per second. Principal photography in:

Anamorphic and flat *).

Presented on: The curved screen in 70mm with 6-track magnetic stereo.

Aspect

ratio: 2,21:1. Country of origin: Canada. Production year: 1966/7.

World

Premiere: 28.04.1967, Ontario Pavilion, Expo 67, Montreal, Canada. German

premiere: 09.10.2011The Ontario Government Department of Economics and Development, Presents "A Place to Stand", A TDF Production. Executive Producer David Mackay. Technical Production by Barry O. Gordon. Filmed and Edited by Christopher Chapman, C.S.C. Sound Kenneth Heeley-Ray. Composer Dolores Claman. Arranger Jerry Toth. Lyrics Richard Morris. Conductor Rudy Toth. Additional Cinematography by Joe Seckerish, C.S.C., Les George, C.S.C. Under the direction of David Mackay. Additional sound recording Bill Foster. Optical printing by Film Effects of Hollywood. Music Recording by Hallmark Studios and Film House-Toronto. Sound Mix by Todd AO. Colour by Technicolor. Producer-Director Christopher Chapman *) While there are some anamorphic shots in the film, most of the footage was shot 'flat' and then cropped to custom aspect ratios by the matte printing. |

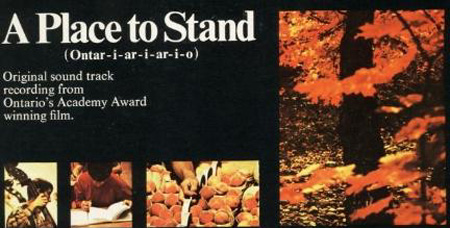

More in 70mm reading: Canadian 70mm Short Films Schauburg 2011 Festival Program The Lost Dominion 70mm Film Festival CINERAMA and large-frame motion picture exhibition in Canada 1954-1974 Internet link: Large format in Canada Christopher Chapman Making of A Place to Stand with Chris Chapman Expo 67 Canadian Film Encyclopedia Part 1 + Part 2 Music disc Christopher Chapman obituary |

Background | |

|

Commissioned as the feature attraction for the Ontario Pavilion at Expo 67 -

the Universal and International Exposition at Montreal, where it was

premiered to the public on April 28, 1967 and presented continuously daily

until October 29, 1967 in a 570-capacity cinema, and subsequently released

theatrically in 35mm anamorphic and 16mm letterbox versions. "A Place to Stand" was produced and directed by Christopher Chapman for the Ontario Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal. The film premiered on April 28, 1967 in a 70mm print by Technicolor, on a screen 66 feet wide by 30 feet high, with six-channel stereo surround sound. Using images, music and sound effects without spoken narration or titles, the film tells about life in Ontario, presenting about an hour-and-a-half of footage in its 18-minute running time. This is accomplished by what Chapman calls his multi-dynamic image technique, a groundbreaking multiple screen, variable picture presentation that allows viewers to see many images within different panels, up to 15 scenes simultaneously on one screen. Nearly every major Hollywood studio purchased prints of Chapman's film to screen for executives, producers and directors. Columbia Pictures distributed the film to movie theatres throughout the United States and Canada. "A Place to Stand" clearly influenced the composition of subsequent film images. An early prominent example of this influence was Norman Jewison's 1968 film "The Thomas Crown Affair", which featured Chapman's multi-dynamic image process in key scenes of the story. Jewison publicly acknowledged Chapman as creator of the technique. Christopher Chapman's "A Place to Stand" was nominated in two categories for an Academy Award, including Best Documentary Short Subject. The film won in the Best Live Action Short Subject category and Chapman accepted the Oscar on April 10, 1968, during the 40th annual Academy Awards presentation at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. George C. Konder |

Scrivener, Leslie Forty years on, a song retains its standing Star-Toronto / 22 April 2007 / page d4 Konder, George Christopher Chapman’s movie A Place to Stand 6 December 2004 |

Awards | |

|

1967 Oscar Win:

Best Live Action Short Subject 1967 Nominated Oscar: Best Documentary, Short Subjects 1968 Canadian Film Awards: Best Sound Editing (Non-Feature) Kenneth Heeley-Ray. Best Film of the Year Christopher Chapman |

|

Promotional Media Releaase Text (1967) (transcribed) | |

The Ontario Pavilion film presentation - A Place to Stand The Ontario Pavilion film presentation - A Place to StandExposition communication is becoming increasingly sophisticated. Among the many varieties of film techniques which have been developed, certain main types may be distinguished. There is multiple screen, where many different pictures are presented on a number of different screens. There is the variable picture, where a single picture may change its shape and size and move on a single screen. The subject of the Ontario Pavilion film presentation is the Province of Ontario itself. To do justice to a subject of such enormous scope and complexity, a combination of these techniques was employed, using the added technical advantage of a system that enables a multiple screen/variable picture to be assembled and projected through a single 65mm [sic] film. The screen on which our film is projected is 66 feet wide by 30 feet high - one of the largest in North America. To the best of our knowledge this is the first time that a combination of these techniques has been exhibited on such a complicated and extensive scale, creating a new dimension in film presentation, not limited by special conditions of an exposition, but allowing world theatrical distribution. | |

Once the technique had been chosen, it was a case of imagining the effect,

discovering the way to shoot for this new format, and working the entire

film out on specially devised editing charts. It was understood from the

beginning that because of shortage in time there would be no opportunity to

make changes in the film once it returned from the complex optical work.

This was a very sobering thought since almost all the rhythms which are

essential to the pace of any film had to be finalized on paper rather than

on the film itself. Once the technique had been chosen, it was a case of imagining the effect,

discovering the way to shoot for this new format, and working the entire

film out on specially devised editing charts. It was understood from the

beginning that because of shortage in time there would be no opportunity to

make changes in the film once it returned from the complex optical work.

This was a very sobering thought since almost all the rhythms which are

essential to the pace of any film had to be finalized on paper rather than

on the film itself.The production was begun by three people in the fall of 1965. The shooting was completed by July 15, 1966, except for an additional 75,000 feet shot by other cameramen. This work was done on a seven-day basis throughout. A total of 200,000 feet of 35mm film was shot out of which the Ontario Pavilion film presentation was to come. Four months after the commencement of editing, the last of the editing charts was completed and shipped to Film Effects where the optical work had to be done. This technique was as new to them as it was to us - on the scale we were doing it. On March 4, 1967, the last for the film returned from it optical work. This was the first time the edited film could be seen. Two days later it was returned for final optical revisions and color printing by Technicolor. The complex six dimensional sound tracks were by then being laid and were complete by March 15. From March 1 to March 16 the music was composed, a demonstration piece having been previously recorded. On March 18 the recording session was held in Toronto with a 45-piece orchestra and a chorus of 15 voices. The film effects track has been closely designed to the picture and new strides have been made in the area of sound to picture. Six track stereo sound accompanies the picture. The track is designed to individualize the screens [sic] where desired, and to create a total environment for the audience. The sound track consists of the sounds of Ontario, the special musical score, and the Ontario song written for the film. This is a new dimension in film which requires a new way to look at the subject, a new way to photograph, a new way to edit, and a new way in communication of the edited concept to the laboratories, and which also requires a new way to view the finished film. One might ask how you can “see” so many pictures all at once. It is not a case of “seeing” all these pictures, but sensing an environment of pictures around one dominant one. The film might be described as a rhythmic kaleidoscope of life in Ontario. In some way, perhaps subliminally, almost every aspect of Ontario appears. | |

Newspaper / Magazine Articles (transcribed) | |

The birth of A Place to Stand

| |

The film for the Ontario Government at Expo 67 is for me the culmination of

a desire I had some years ago to try a moving multiple screen technique. I

had never seen it done but I, myself, had experimented with panning a

projector over a very large screen and was fascinated by the viewer’s

relationship to a panning camera and a panning screen. The film for the Ontario Government at Expo 67 is for me the culmination of

a desire I had some years ago to try a moving multiple screen technique. I

had never seen it done but I, myself, had experimented with panning a

projector over a very large screen and was fascinated by the viewer’s

relationship to a panning camera and a panning screen.In the conventional film for example, when viewing a pan across a landscape we watch the landscape move across a static screen. As soon as that screen moves with the pan we are watching a static landscape being revealed by a moving screen or “window”. While I did not explore this to any great extent in the Ontario film it was the basis for my direction of thought. It was this idea plus a dynamic screen technique (that I had heard of but not seen) that led me to explore the idea when I was originally making a presentation for the Telephone Association Pavilion at Expo 67. The dynamic screen consists of a matte covering the whole picture but allowing one part of the picture to be revealed through a “window”. This “window” would increase or decrease in size. A phone call to a lab in Hollywood warned me against the dynamic screen technique as it had been a failure in its latest adoption. My concern was whether it was a failure due to technical difficulties or creative misuse. Later while already well into the Ontario film we saw a print of "A Door in the Wall", using the dynamic screen, and it was clear that its failure was creative not technical. When I was asked by David Mackay of TDF to produce and direct the Ontario film, there was no idea as to what the project involved. The only thing we knew was that we had to produce an unusual film in 18 months. My one desire then was to make a film that would give everyone as big boost and make them feel good, but it was not easy condensing Ontario - particularly a province that is so industrialized. There was no script. Time would have been required to develop a definite theme idea but time was extremely limited. Out of our discussion emerged the dynamic-multiple screen concept that I had long dreamed of. The key was a gigantic flat screen - a “mural” surface that one really could move upon and break up with multiple images. Barry Gordon, whom I had requested to be technical producer for the film, immediately set off for Hollywood to discover whether the required complicated processing could be done. Shooting on location was exploring completely new territory. An early mistake was making the shots I wanted to retain on the screen through a complete sequence of events, too short. The movement of the camera and the action within the frame had to be considered in a new way, which in documentary shooting is not always possible. I had to consider less interesting shots or deliberately make a shot less interesting. Such a shot might be an important element in a sequence but not the dominant one. A multiple of equally interesting shots might confuse the audience. Shots that I used to look at as normal academy frame proportions I now looked at with an eye to vertical frames and horizontal frames, odd frames, small frames and large frames. Since access to a 70 mm camera [sic] was impossible due to lack of time, another difficulty encountered was deciding, through consultation with Barry Gordon, whether a shot would retain its clarity when blown up to 70 mm. Blowing up 35 mm to such as screen as 66' x 30' which is the Pavilion screen, meant a very great stretch and not very many shots could stand it. This meant I would shoot a full screen landscape as 2 divided screens, which to me was unsatisfactory. Going to 3 or 4 composite screens was not the same problem as I used these as part of the design format. 180,000 feet of film were shot. Some additional footage of material I had not time to shoot myself was shot by David Mackay, using TDF cameramen. After completely familiarising myself with the footage, I worked out a storyboard of the entire film. Although it was theoretical, it did give me an impression of how the subject matter could be structured. I then had to devise my own charts as did Barry Gordon who translated my charts into his own lab charts in a language that the lab could comprehend. The lab was most impressed with the clarity of Barry Gordon’s technical instructions. | |

To edit the film I had a 2 picture head moviola which was the closest one

could get to visualising the results. One could only use it to compare

actions of any 2 shots at one time and designate the length of shots. In

normal film editing, one works with the actual footage and soon discovers

that frame or two on any shot can make a difference in rhythm. With the

Ontario film I could never “see” the film develop. The charts indicated the

movement of the shots. Because of the shortage in time their could be no

changes in structure in any of the sequences once they returned from the

lab. It was a tremendous discipline for me, for once I had made a creative

decision, I could not change my mind. The entire concept of development

therefore, was on paper in chart form. To edit the film I had a 2 picture head moviola which was the closest one

could get to visualising the results. One could only use it to compare

actions of any 2 shots at one time and designate the length of shots. In

normal film editing, one works with the actual footage and soon discovers

that frame or two on any shot can make a difference in rhythm. With the

Ontario film I could never “see” the film develop. The charts indicated the

movement of the shots. Because of the shortage in time their could be no

changes in structure in any of the sequences once they returned from the

lab. It was a tremendous discipline for me, for once I had made a creative

decision, I could not change my mind. The entire concept of development

therefore, was on paper in chart form.Ken Heely-Ray of ADS (formerly of the NFB) laid the extremely complicated 6 tracks of film effects and music. It took 6 days to mix the 6 tracks at Todd-A-O in Hollywood. When all the sequences of the film were finally assembled after 4 months of optical work, there were 2 days to assemble them, see the completed film for the first time and return it to the lab for final processing. This gave the composer Dolores Claman 2 weeks to write the musical score which was arranged by Jerry Toth. The basis of the song “A Place to Stand” was suggested by David Mackay from a quotation of Archimedes, and the lyrics were written by Richard Morris. I am very grateful to the Commissioner of the Ontario Pavilion, J.W. Ramsay who, although he must have been anxious at many turning points, particularly since we were delving into such an unknown area of film, never once interfered in content, direction or completion. David Mackay of TDF also allowed me complete freedom, leaving all decisions to me. I feel that great deal of the film’s success is due to this trust. The film was conceived as a mural or painting would be. Its development was very personal, consequently it has the bad and the good of a single concept. My own connection with the film now is only through the audience. Perhaps some day I will view it unattached. | |

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 21-01-24 |