"Seasons in the Mind" | Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Bill Kretzel, Ottawa, Canada | Date: 02.10.2011 |

"Seasons

in the Mind" (0:22). Filmed in: 35mm 4 perforations, 24 frames per

second. Principal photography in: Panavision. Presented on: The curved

screen in 70mm with 6-track magnetic stereo. Aspect ratio: 2,21:1. Country

of origin: Canada. Production year: 1971. World Premiere:

22.05.1971. German premiere: 09.10.2011 "Seasons

in the Mind" (0:22). Filmed in: 35mm 4 perforations, 24 frames per

second. Principal photography in: Panavision. Presented on: The curved

screen in 70mm with 6-track magnetic stereo. Aspect ratio: 2,21:1. Country

of origin: Canada. Production year: 1971. World Premiere:

22.05.1971. German premiere: 09.10.2011A Milne-Pearson Production. Produced and Directed by Michael Milne, Peter Pearson. Cinematography Tony Ianzelo. Editor Arla Saare. Post-Production Supervisor Ken Heeley-Ray. Music Larry Crosley. Talent Night Sequence. Mac Beattie. Sound Editor Jim Hopkins. Rerecording Clarke Daprato. Studio Sound Services Optical Effects. Film Technique Limited. Filmed in Panavision 35 through Cinevision, Canada. Colour by Technicolor. Production Assistants Diane Amsden, Rob Iveson, Stephen Patrick. A portrait film of Eastern Ontario directed by Peter Pearson who’s films include the award winner’s like “The Best Damn Fiddler from Calabogie to Kaladar" (1968) and the classic Canadian feature film, "Paperback Hero" (1973). "Seasons in the Mind" includes a talent show section set in Arnprior, Ontario. "Seasons in the Mind" - had a co-director credit: Michael Milne (who was Pearson's business partner and had been art director for Best Damned Fiddler...) | More in 70mm reading: Canadian 70mm Short Films Schauburg 2011 Festival Program The Lost Dominion 70mm Film Festival "Seasons", A Short Film in 70mm CINERAMA and large-frame motion picture exhibition in Canada 1954-1974 Internet link: Large format in Canada Lawrence Crosley |

Background | |

70mm

frame blow-up from "Seasons in the Mind". Color restoration by Schauburg

Kino 70mm

frame blow-up from "Seasons in the Mind". Color restoration by Schauburg

KinoCommissioned as one of four large-format short subject productions for Ontario Place, Toronto - a lakeside recreation and entertainment complex developed by the provincial government to showcase culture and tourism, where it premiered to the public on May 22, 1971 as part of the daily repertory screening schedule to September 6, 1971 (and also in the spring of 1972) in Cinesphere, an 800-capacity film venue designed for the first permanent IMAX installation. Michael Milne: ....we ended up shooting in 35mm Panavision format and blew up the film to 70mm. That gave us a lot of technical leeway for the special effects. We created the visual effects in Toronto. Then I spent two months at Technicolor, timing and finishing the 70 mm print. The score was recorded in 12 tracks at Todd A-O in Hollywood. We ended up with 6 sound tracks on the 70mm print and 6 more tracks running in synch on a 35mm magnetic tape. It was spectacular wrap around sound! Read full story | |

Newspaper / Magazine Articles (transcribed) | |

Ontario Place film more poem than documentary

| |

70mm

frame blow-up from "Seasons in the Mind". Color restoration by Schauburg

Kino 70mm

frame blow-up from "Seasons in the Mind". Color restoration by Schauburg

KinoWhatever the Ontario government had in mind when it commissioned "Seasons in the Mind" now running at the Cinesphere of Ontario Place, “documentary” hardly describes it. Poem, maybe Elegaic. Created by Michael Milne and Peter Pearson, the film is in 70 mm, running for 22 minutes, and uses a 12-track stereo system. The team’s previous production of "The Best Damn Fiddler from Calabogie to Kalladar" won the Canadian Film of the Year award in 1969. Following the cycle of the four seasons, the deep-rooted interdependence of life and nature, "Seasons in the Mind" is a mental image, a vague memory, something to haunt us in our asphalt and steel. It seeks to express the team’s respect for the land and people of Eastern Ontario. But first impressions are misleading. The vestigial, isolated quality of the amateur night in Arnprior sequence seems to lay an intense focus on the awkwardness of the participants, and we city-slickers may be tempted to laugh. But when a single snapping-turtle crossing the highway holds up an endless line of suburbanites on their compulsive drive to the cottage country, nature laughs at the city slickers. This portrait of the people of the region makes us feel the rootlessness of our own existence. It is a romantic view of the land, and parts of it, like the harvest sequence, suggest the muted force of a terrible nature very reminiscent of the landscapes of Thomas Hardy. As a poem, a haunting memory, the film works. | |

Magic film makers on a real low budget

| |

Kate Reid, so the story goes, 18 months ago was judging a beauty contest

with Ontario Place chief James Ramsay and, in her inimitable fashion, said

something like this: Kate Reid, so the story goes, 18 months ago was judging a beauty contest

with Ontario Place chief James Ramsay and, in her inimitable fashion, said

something like this:“If you guys at Ontario Place know what you’re doing, you’ll hire Mike Milne and Peter Pearson to make a movie, they’re terrific. Take it from me.” Ramsay did just that. Within several days, Milne and Pearson, Toronto movie makers who keep a low profile despite their considerable credits - including nine Canadian Film Awards in 1969, seven of them for "Best Damn Fiddler", a compelling National Film Board drama starring Kate Reid - were in Ramsay’s office negotiating a deal. Ramsay had a huge map of the province and he told the pair he was commissioning a series of “regional spectaculars” for showing in Cinesphere, the Ontario Place bubble, and would they pick an area. Eastern Ontario had been the setting for Best Damn Fiddler, the pair felt at home there and chose it. Their movie, completed on a $270,000 budget, the first here with a 12-track stereo sound system. It is being screened daily from this week on in Cinesphere. It is one of six to be shown in rotation until Ontario Place closing day Oct. 11, free of charge. “There was no sense,” Milne said yesterday, “in trying to duplicate Christopher Chapman’s feat, so we set out to make something that wasn’t just another travelogue. We tried to get at the area’s most important element, and we found that to be isolation... people are living mostly on farms separated from each other... even industry is spread out, all this except for Ottawa.” Their movie, "Seasons in the Mind", captures the four seasons in eastern Ontario and matches their central colors to human moods and the birth-to-death cycle. Originally, Ramsay told then to “go out and make the biggest movie in the world,” because then Cinesphere was to have shown movies projected on the wall and ceiling, but costs proved impractical and finally only one mammoth screen was installed. “The 20-minute film,” Pearson said, “is the hardest film form in the world. You have to show something of the land, something of the people, the seasons, a range of areas and activities and cram them all in 20 minutes. “It is the only film form indigenous to Canada. It is the ‘short’ documentary. It was really difficult to find a form of doing it that would make everything work. The film represents our attitudes over the past five years about the area.” There are technically tricky sequences - one involving figure skaters against a black background with no ice beneath them; simple ones - a huge turtle blocking a highway causing a traffic jam; and nostalgic ones - recollecting the area’s past in memories of the church and rural days. "Seasons in the Mind" is in the 70 mm process projected 75 feet wide by 35 feet high, leaving the Imax film "North of Superior" to be the biggest in the world. Milne and Pearson share one problem with the other Ontario Place film-makers. No credits are allowed at the end of their efforts. Ramsay personally has ordered them banned. “Ramsay decided,” according to one Ontario Place source, “that credits would take a minute each and that could go up to five minutes longer in clearing the theatre out for the next crowd. That kind of time would be valuable considering the crowds still expected.” Milne and Pearson don’t need that anonymity, now that their Ontario Place contract barring them from working on any other movie for a 12-month period has expired. “Tell the world that we’re unemployed,” grumbled Pearson. They are, but their company is breaking up with Millen returning to entirely sponsored film making and Pearson left to his plans of directing feature movies. The pair has screen rights to the Sinclair Ross novel, As for Me and My House, and an original script by Charles Israel. Now if Kate Reid would only tell the financiers that Milne and Pearson are terrific, take it from her, Pearson could get back to the promise of Best Damn Fiddler... | |

How Milne-Pearson Productions made film for Ontario’s Cinesphere

| |

No doubt it was once all comparatively simple. Movie screens came in one

size, films stocks in one speed, sound on one track. No doubt it was once all comparatively simple. Movie screens came in one

size, films stocks in one speed, sound on one track.But today the complexities and possibilities of film-making are infinite, and to explore them all demands not only art and imagination, but also knowledge of chemistry, mathematics and electronics. Certainly all are involved in making film for a theatre such as the Cinesphere. Glowing like a moon on the Toronto waterfront, the Cinesphere is the dome-shaped theatre of Ontario Place, where the provincial government is out to prove once again that Ontario remains a place to stand - and not just in line for unemployment benefits. Milne-Pearson Productions (Peter Pearson, Michael Milne) landed the contract to make one of the Cinesphere movies, and the story that follows is extracted from the producers’ own account of how they thought through the creative problems and, with the help of Toronto specialists, coped with the technical challenges. The Cinesphere itself is a startling theatre wired to play 24-track stereophonic sound, faced with an eighty-by-eighty foot screen, equipped to handle 16mm, 35mm, 70mm and IMAX. Unlike the one-movie pavilions of Expo 67, this is a permanent theatre with a changing program. The government asked Milne-Pearson to make a Cinesphere film about eastern Ontario, a triangle of seventeen counties embraced by the Ottawa and St. Lawrence rivers. Their first problem in the film’s conception was to develop a style compatible with both the most modern film theatre in the world and an area of Ontario that is more traditional than futuristic. They wanted to focus on specific people and events without locking the film into a documentary reality form: “to elevate certain sequences to the level of impression, memory, fantasy, or dream, without losing a sense of what in fact our subject matter was.” As they saw it, the challenge was to find a form that would link one isolated event to another, and move from one style to another. Eventually they settled on three devices to create a visual unity. The first was color. “In our shooting we emphasized the blue tones of winter, the green of spring, the red of summer, and the yellow of fall.” But color alone was not enough structural glue, so they followed the seasons in order which let them join sequences which otherwise had no natural edit. The they decided to relate the seasons to specific life experiences (birth, learning, work, old age, death). “It’s important to emphasize that we were more interested in the intrinsic nature of the event than its symbolic importance. We were looking for those specific moments which would best typify the lives of the people of eastern Ontario.” Sequences with spiritual affirmation (learning, for example) fitted together comfortably. Thus in the spring sequence it was easy to combine scenes of a young girl learning to ride her bicycle, a new-born colt learning to walk, and a young solider learning his drill routine. Four years earlier, while shooting "The Best Damn Fiddler from Calabogie to Kaladar", CBC’s big award-winner. The same film-makers had regularly dropped into the Renfrew Hotel for talent night. The memories of those evenings gave then the idea for filming a talent night in Arnprior. The isolation of the winter rural landscape led to a sequence of figure skaters alone on a lake. The dialects of the regions and the reminiscences of old people became the basis of a “nostalgia” sequence. Traditional values of family, church and state provided the basic ingredients for a sequence on the harvest. There was not enough money to make the movie in 65mm so they settled for Panavision anamorphic 35mm. This let them do all the lab and optical work in Canada, except for the final Cinesphere release prints - 70mm blow-ups by Technicolor in Hollywood. Optical effects became very important and account for fifty percent of the finished film. “We reserved effects chiefly for sequences which would evoke impressions, memories, fantasies, or dreams.” Effects include: super-imposition of high contrast images over continuous tone scenes; combinations of freeze-frames and live action; color changes within a scene; moving mattes; aerial zooms. | |

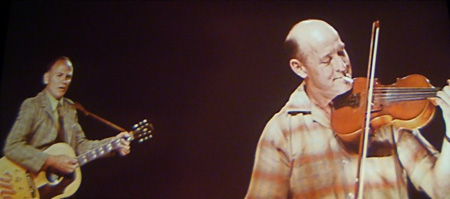

The Talent Night sequence in its final form, has various entertainers

appearing and disappearing against a black field. At one point there are

four sets of step dancers shown full figure in each corner of the frame,

with a girl in medium-close-up singing in the centre. Although each set of

dancers was filmed separately no frame lines can be seen. The Talent Night sequence in its final form, has various entertainers

appearing and disappearing against a black field. At one point there are

four sets of step dancers shown full figure in each corner of the frame,

with a girl in medium-close-up singing in the centre. Although each set of

dancers was filmed separately no frame lines can be seen.To achieve this effect, the original negative was over-exposed by 1˝ stops then processed normally. This increased the contrast ratios while, to the partners’ delight and contrary to expectations, not creating unacceptable grain. Each act was shot as a full-frame figure against a black velvet background. The editor then sat down with a film strip projector and drew frame-by-frame charts to plot the movements of each figure or group. She then prepared timing charts for the opticals to keep them in sync with the master three-track stereo recording of the sequence. Film Technique made specially timed interpositives of all the footage and then printed each frame according to the charts for a final color-balanced optical negative for producing release prints. A figure skating sequence starts out with an abstract forest effect achieved with nine black-and-white still photographs of trees against a blue field. The camera tracks through the tress and ends up discovering figure skaters in their leaps, lifts and spirals. At first the trees and figure skaters were conceived as two separate sequences but were put together in the editing room because the similar styles combined so easily. The forest photographs were taken to high contrast, and paper positives were made. The aerial tracking effect was created with the animation camera and a computer. Each tree was photographed separately and combined on the optical camera. To film the figure skaters, the partners built a skating rink in the middle of Lake Simcoe and shot on a an overcast day to eliminate the horizon. The skaters were dressed and made-up in black, and the action shot in slow-motion on black and white. The negative was underexposed 1˝ stops and overdeveloped by 2 stops. High contrast positives from the overly contrasty negatives cleaned up most of the minor flaws in the original material. The final composition included the misty blue background and the sun. “We tried several different background effects before finally deciding on a pick-up of a beautiful yellow autumn mist that cameraman Tony Ianzelo had shot one morning.” Film Technique color-corrected the interpositives from yellow to blue-green. “Because the mist negative was too short for the action, we did a series of dissolves on the negative and created a loop. Another shot, an undulating sun-star through the trees was an upside-down blow-up of the sun in still water. All the high-contrast components were then added on the optical camera and the sequence completed as one piece of film. Film Technique in Toronto handled all the optical work under the supervision of Brian Holmes. The sound track like the optical effects was designed to be more evocative than imitative. Larry Crosley wrote a score in four parts - one for each season. Jim Hopkins plotted and edited the sound effects on more than a hundred mono tracks. At Studio Sound, Clarke Daprato had to mix in four reels each with 25 mono effects tracks, a three-track sync for two sequences, plus the twelve tracks of Crosley’s original music. The result is an unusual and complicated sounds tracks that adds considerably to the Cinesphere experience. Six of the tracks are carried magnetically on the film and the other six on a 35mm magnetic dubber synchronized to the projector. The producers sum up: “Whether in fact the film expresses the spirit of eastern Ontario is a decision for the people of the region to make. The film has none of the landmarks of the region, no Parliament Buildings, no St. Lawrence River, no changing the guards at Fort Henry. But we hope it expresses our deep respect for the people of eastern Ontario, who have an enduring sense of their land, its seasons, and, most of all, of themselves.” | |

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 21-01-24 |