Projection and Wide Film (1895-1930) |

Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Rick Mitchell Film Editor/ Film Director/ Film Historian. Work published posthumously | Date: 15.03.2014 |

|

In his first accounts of his work in developing motion pictures, W.K.L.

Dickson claimed to have initially projected a talking picture of himself on

the wall of his laboratory for Thomas Edison in October, 1889. Subsequent

research, particularly revelations about, and surviving examples of,

Dickson’s earliest work, have raised questions about whether this incident

occurred or would even have been possible using the equipment with which he

was working at the time ; Edison himself later denied it in court

proceedings . However, if Dickson’s original intent had been projection on a

screen, especially in a theatrical setting, it’s possible he might have

chosen a wider frame than 1.33:1. The precedence for projection had already been established. Earlier in the 19th Century, a number of devices had been developed to allow individual viewers to experience the persistence-of-vision phenomenon by flashing a series of images with elements in differing positions before their eyes in such a way as to make them appear to be in motion . Most of these involved sequential drawings and later posed sequential photographs such as those of Coleman Sellars, those from a sequential series of cameras as used by Eadward Muybridge in his motion studies, or Etienne Jacques Marey’s multiple lens “gun camera”. In 1853 Lieutenant Baron Franz von Uchatius of the Austrian army was the first to combine such a device with the “magic lantern” to project the “moving” images to a large audience. By 1877 two Frenchmen, Jean Louis Meissonier and M. Emile Reynaud, had developed a device called a Zoopraxiscope which involved the projection of the images from a rotating glass wheel through an opaque shutter disc revolving in the opposite direction. A program of such images was shown at the Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1893, in the specially built Zoopraxographical Hall. Ironically the Edison peepshow Kinetoscope debuted at this Exhibition, and the Zoopraxiscope presentation further stimulated a desire for the projection of the Kinetoscope motion pictures as well. Edison continued to resist requests from Dickson to develop a projector, soon a source of friction between them, feeling that presenting the films to large audiences at one time would dry up interest in them within a couple of years. Events quickly proved Edison wrong. Though not developed by them, the first motion picture projector and the first official use of a film stock and frame wider than 35mm grew out the Edison Company’s efforts to expand their library of films for the peepshow Kinetoscope by photographing as many appropriate novelties, famous personalities, and even bits of dramatic and comedic productions as they could cram into the @20 sec. running time of the 50 ft. films. Two young Virginians living in New York City, Grey and Otway Latham, thought the then very popular sport of boxing would provide appropriate Kinetoscope subjects, though the short running time was problematic. In 1894 they were able to make a deal with the Edison Company to do a prize fight film for presentation in special Kinetoscopes. A fellow Virginian, Enoch J. Rector, worked out a method of increasing the amount of film the camera could photograph to 150 ft. and developed the modified Kinetoscopes to handle it. Michael Leonard and Jack Cushing were photographed in six abbreviated rounds and the results were made available in a row of the six special Kinetoscopes, each containing one round of the fight. When the popularity of this film began to fade, the Latham brothers shot a specially staged fight between “Gentleman Jim” Corbett and Pete Courtenay. But the Latham brothers felt their fight films would be more successful if they could be presented to large audiences by projection onto a screen. They put the question to their father Woodville, a chemist, who, after checking out a Kinetoscope, stated there was no reason the films could not be projected and set up the Lambda Company with the brothers, Rector, and Eugene Lauste to build a machine that would do so; later in his career Lauste would be one of the first to experiment with recording sound on film . Otway Latham had also befriended W.K.L. Dickson, who, frustrated in his efforts to get Edison to allow him to develop a projector, became excited about the Latham project. One immediate problem: the Lambda partners were still following the practice of moving the film continuously past the lens and using a rotating shutter to flash the various frames onto the screen. Though acceptable for the peepshow Kinetoscope, this approach did not allow enough light to get through the film to get anything near an acceptably viewable image when projected. Woodville Latham suggested using a larger film, which would also help them evade Edison’s patents. They chose a 51mm width for reasons that have never been determined, and a wider aspect ratio, about 1.85:1, to better accommodate their chosen subject matter. Dickson had confided to Otway Latham the necessity of an intermittent movement in the camera to allow for proper exposure of the negative. Unfortunately, the jerking involved caused the huge roll of film to break. Rector solved this problem by adding a sprocket above the lens that fed the film into a loop from which it could be jerked down past the aperture. This important development would become known as the “Latham Loop.” On April 21, 1895, the Lambda company gave the press the first officially documented presentation of a motion picture projected onto a screen: some boys playing in a park while a man seated on a bench calmly puffs on a pipe. (According to some sources, the “actors” were Eugene Lauste and his sons.) The New York Sun immediately sought a comment from Edison, who poo-pooed the demonstration and the projector as inferior to work going on in his plant that would soon be revealed to the public . Undaunted, Otway Latham staged a fight between “Young Griffo” and “Battling (Charles) Barnett” on the roof of Madison Square Garden and on May 20, 1895 the four minute film was officially put on public exhibition. Though the results were still imperfect, the Lambda Company continued to make and market its projector, which they called the Pantoptikon, and the films made for it, for about the next two years. The major flaw was the continuous movement of the film past the lens in projection. Working independently Thomas Armat in the United States, Robert W. Paul in England, and the Lumiere brothers in France would discover that intermittent movement was also necessary for projection; in fact each individual frame needed to be held longer for this purpose than for photography. Armat and Paul had worked with Kinetoscope films in their experiments. Edison would buy out Armat’s patents and Armat would even supervise the debut of “Edison’s New Projecting Kinetoscope” at Koster & Bial’s Music Hall in New York on Apr. 23, 1896. However, Edison had shortsightedly seen no point in filing for patents outside the United States, so Paul was free to figure out how to make his own camera and begin making his own films using the format developed by Dickson. The Lumieres also went with this format but made two changes: two round perforations on either side of each frame, and a reduction of the filming speed from the Edison and Lambda rate of 40 frames per second to the 16 fps that would become the unofficial standard rate for silent films. In fact, both filming and projection rates varied according to the effects desired by cameramen and the whims of projectionists. As a result, what became the official sound speed of 24 fps derived from AT&T’s averaging of filming and projection speeds in 1925. Both Lee De Forest and Theodore W. Case did their experiments at different speeds with the latter settling on 24 fps for the sake of compatibility. The essentially standard picture format of 1896 made it possible to print films shot with the Lumiere’s camera-printer-projector Cinematographe onto stock that could be used in the Armat and Paul projectors and vice-versa. This was apparently also the reason why the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company chose the basically 1.33:1 aspect ratio even though they were using a 68mm negative stock. This stemmed from their efforts to not infringe on Edison’s patents, something to which they were particularly sensitive because one of their founders was W.K.L. Dickson, who’d been fired by Edison in 1895. The Biograph camera did not use perforations in the negative and it used an armature, rather than an intermittent sprocket, to jerk the film past the lens. The images were initially printed onto cards that were used in a peepshow device, but a projector was later developed for the wide film and subsequently the images were reduction printed to 35mm, for which Biograph would subsequently abandon the wide negative about the time of the rise of the nickelodeon. Enoch J. Rector, a partner in the Latham’s Lambda Company, was still fascinated by boxing films and had actually promoted a couple of fights so he could photograph them, most notably the Corbett-Fitzsimmons fight held in Carson City, NV on Mar. 17, 1897. Rector had this fight photographed with special cameras he’d developed using 63mm film with a 1.66:1 aspect ratio and a filming speed of 24 fps. This was the last commercial use of wide film in the United States for thirty years. Experimentation and occasional presentation with wider films continued in Europe through the turn of the 20th Century. In 1892, before there was any public record of Dickson’s work for Edison, Carl and Max Skladanowsky, working in Germany, slit in half the 89mm negative introduced in 1890 for the Kodak No. 2 still camera for use in a motion picture camera they’d developed. Their 30 x 40mm images were printed onto 54mm wide strips of eight pictures each spliced end-to-end with three grommets. They also perforated the edges of the print, but not the negative, and strengthened those perforations with grommets as well. In 1895, Skladanowsky designed another camera that used 63mm negatives slit from a 126mm original, which he used to take shots of Berlin and other places that were shown at the Berlin Wintergarten in Nov. 1895 . The frame was 40 X 50mm and had one 2.3mm perforation on each side of the frame line. It was printed onto 65mm stock with four perforations per frame . Toward the turn of the 20th Century, a number of French inventors, including the pioneering Lumieres, worked with film stock larger than 35mm, up to 75mm, but with one exception, maintaining the approximately square frame. For example: “Oscar B. De Pue, partner of Burton Holmes, in 1897, purchased a machine in Paris from Leon Gaumont for taking 60 mm. wide film then put up in one hundred foot lengths, unwinding and rewinding inside the camera on aluminum spools; not a daylight proposition, but a dark room model. This machine he took to Italy and the first motion picture turned out on the machine was of St. Peter's Cathedral with the fountain playing in the foreground and a flock of goats passing by the machine. He then took other pictures of Rome and from there visited Venice, where pictures of the canal and Doges Palace and the waterfront along the canal with views of feeding the pigeons at St. Marks with the great cathedral in the background. From there to Milan for a scene of the Plaza in front of the Milan Cathedral; thence to Paris where pictures of the Place de la Concord with its interesting traffic and horse drawn busses, fountains, obelisks, statues, bicycles, wagons, trucks and carriages were made. All the life of that day, after thirty two years, is in striking contrast to the present. “These negatives are still in his possession although the prints for them have long since been lost track of on account of our having changed from that size of picture to the standard size. “This Gaumont wide film camera was used for five years by Mr. De Pue and most of the negatives, many of which are of great historic value, are still in good condition, so that either full size or standard sized reduction prints can still be made from them.” The exception was Cinéorama, a forerunner of both Cinerama and Disney’s Circle-Vision 360, presented by Raoul Grimoin-Sanson in Paris in 1900. It involved photography from ten interlocked 70mm cameras arranged in a circle and suspended from a balloon flying over a number of scenic locations. The resulting hand colored prints were shown on a circular screen to an audience seated inside a simulated balloon basket and were reportedly quite effective. Unfortunately, the projection booth was beneath the audience and the arc lights heated it to over 100 degrees Fahrenheit. In light of a disastrous fire at a charity bizarre three years earlier that was traced to a projection machine and its flammable nitrate film, the police shut the show down after three days . Cinéorama was a forerunner of the use of motion pictures in expositions such as World’s Fairs and special venues designed to exploit experimental technologies. But the commercial development of motion pictures was taking off in a direction that was more receptive to the standardization of 35mm film and the 1.33:1 aspect ratio. |

More in 70mm reading: Introduction to Projection and Wide Film (1895-1930) Prologue to Projection and Wide Film (1895-1930) Who is Rick Mitchell? Rick Mitchell - A Rememberance Projection and Wide Film (1895-1930) 1930's Large Format Equipment at the USC Archive The Bat Whispers in 65mm The Bat Whispers Early Large Format Films Grandeur Magnifilm Natural Vision Realife Vitascope Internet link: |

An industry develops, especially in the United States | |

|

Although the Lathams had given the initial public showing of their

Pantoptikon films in a storefront in New York and the Lumieres had shown

theirs in the basement of a Paris cafe, most early screen presentations were

set up in the kind of amusement parlors that also used the Kinetoscope and

Mutoscope peepshow devices, and in vaudeville houses, especially after the

Edison Koster & Bial’s Music Hall presentation. As the popularity of motion

pictures spread, itinerant exhibitors would buy projectors and films and

travel around the country giving shows in stores, churches, and other

auditoriums . (Though set twenty and thirty years later, the Australian film

The Picture Show Man (1977) and the black church sequence in Preston Sturges’

Sullivan’s Travels (1941) give apparently accurate depictions of such

presentations.) Some traveling exhibitors later set up permanent facilities

in empty stores in smaller cities and towns, and, as early as 1896, theaters

were built specifically for showing films in, among other places, Chicago,

Toledo, New Orleans, and Los Angeles . The product being shown, however, was not much more advanced than the early Kinetoscope films: vaudeville performers, bits of comedy, etc. The smaller, hand-cranked Lumiere Cinematographe and the camera developed by Robert W. Paul in England could easily be used outside, which added international scenic views to the available material; in fact the Lumieres sold their combination camera-printer-projectors at a discount if the buyers would send dupable prints or negatives back to Paris for inclusion in the library of subjects they sold to exhibitors. By 1900, this limited repertoire of subjects began to bore audiences in fixed situations, especially vaudeville houses, which began moving them from the top spot on the bill to the bottom, hopefully to clear the house for the next show. Something new was needed, and the popularity of the comic bits and dramatic excerpts like The May Irwin-John C. Rice Kiss (1896) and The Execution of Mary-Queen-of-Scots (1897) pointed the direction toward story-telling films. The most notable early work of this type was done by French magician Georges Melies, who started out making short vignettes that combined established stage illusions with the possibilities of trick photography he was discovering. He soon advanced to combining these tricks into narrative tableaux of up to 1000 ft. in length, his most famous being A Trip To The Moon (1902), which was extremely popular and possibly influenced Edwin S. Porter in making The Life of an American Fireman (1902), and most importantly, The Great Train Robbery (1903). At this far distant time, it’s impossible to determine why this first western had the impact it did. In addition to the Melies films, there had been other narrative films, including some involving action and chases. But Robbery’s popularity revived public interest in motion pictures, led to an explosion in the production of simple one reel dramatic and comedic films, at least one a day from most of the proliferating production companies, and the establishment of theaters specifically set up to show them, even in small towns which didn’t have a legitimate theater or vaudeville house. Initially exhibitors bought their films outright from the producing companies, which left them with a stock of films after their audiences had seen them. They began to exchange them with other exhibitors for their used films. One exhibitor reportedly set up a room in his building where fellow exhibitors could do this, the supposed source of the term film exchange. In 1902, Harry Miles, who two years earlier had bought a camera and shot film in Alaska, came up with the idea of buying films from the producing companies and renting them to the exhibitors, the foundation of the distribution system that exists today, and also of what would develop into the motion picture industry . Naturally this required standardization of projectors and print stocks, which in turn called for the standardization of cameras and negative stocks. Though the Dickson-Edison 35mm 1.33:1 format dominated, there were many variations to get around the Edison patents and his constant lawsuits over claimed infringements on them. “An advertisement in Hopwood’s ‘Living Pictures’ edition of 1899 offers the ‘Prestwich’ specialties for animated photography ‘nine different models of cameras and projectors in three sizes for 1/2 inch, 1-3/8 inch and 2-3/8 inch width of film.’ Half a dozen other advertisers in the same book offer ‘cinematographs’ for sale and while the illustrations show machines for films obviously of narrow or wide gauge no mention is made of the size of the film.” Getting Edison’s chief competitors to pool their patents with his in the Motion Picture Patents Company resolved this plethora of formats and led to such other standardizing developments as a finally perfected film perforator by Bell & Howell. The Motion Picture Patents Company licensed the use of cameras and projectors based on the pooled patents. Perhaps if they had just stuck to this, they would have brought order and discipline to the expanding industry that would have allowed it to also develop artistically. But the Patents Company set out to totally control the industry instead, stimulating opposition to its dictates , such as limiting the maximum length of all films to 1,000 ft. or insisting on only full shots in dramatic films at a time when American filmmakers were finally beginning to explore the narrative potential of the medium. Feisty Trust member Vitagraph made The Life of Moses in five reels and a version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in three (both 1909) but was forced to release them a reel a week, while D.W. Griffith and his cameraman Billy Bitzer were upsetting their bosses at Biograph by moving the camera closer for portrait length studies of his players. Griffith also made a two-reeler, His Trust (1910), but it was released as two films: His Trust and His Trust Fulfilled. However, in the case of his subsequent two reel version of Enoch Arden, exhibitors held up the first reel until the second was released, running them both together and establishing the precedence for longer films . At the same time, just as many entrepreneurs of the era were attracted to motion pictures the way their successors would be attracted to the computer world ninety years later, it was really too late for the Trust to impose its will on the entire developing industry. Using bootleg cameras and film imported from Europe, early producers like Carl Laemmle made films that increasingly violated Trust rules. It was to get away from detectives hired by the Trust to disrupt such productions and wreck their cameras that the American film industry moved away from the New York area and ultimately settled in then primitive and almost always sunny Southern California. No such limitations existed in Europe, especially on the continent, where serious artists had not looked down on motion pictures the way the British, and the American culture mavens who then took their cues from them, had. The French were the leaders in this regard, and in 1908, in a questionable attempt to raise the status of motion pictures, a company called the Film D’Art was formed to film excerpts from famous novels, plays, and even ballets. Surviving examples show that these were merely photographic records shot from the equivalent of front row center of performances with actors mouthing unheard dialog while gesticulating to the rafters. The “common” people who were the most dependable audience for films in France rejected these films but they did attract the middle and upper classes , and one of them initiated the next step in a revival of interest in Wide Screen. One of the most famous stage actresses of her time, the “Divine” Sarah Bernhardt, allowed herself “to be put in pickle for all time” in a number of films made by the Film D’Art and others, the best known of which was Queen Elizabeth (Eclair; 1912), made in 4 reels . Adolph Zukor, one of the many entrepreneurs who had moved from the clothing business to nickleodeons, which he’d later sold to the Trust, bought the American rights to the film and when the Trust would not agree to its being shown in its entirety as a special presentation, approached famous stage producer Daniel Frohman about presenting it in one of his legitimate theaters, a presentation the Trust would not dare attempt to disrupt. Although films had been shown in legitimate theaters in Europe, the presentation of this film at New York’s Lyceum Theater on June 12, 1912 cued interest in the United States in showing longer films, especially spectacles imported from Italy, in legitimate theaters, and also in building comparable palaces exclusively for films, beginning with the Strand Theater on New York’s Broadway, which opened on April 11, 1914 . That same year, Zukor, who after his success with Queen Elizabeth had formed a company with Daniel Frohman and his brother Charles called Famous Players In Famous Plays to make just those kind of films, made a distribution deal with the newly formed Paramount Pictures, as would the recently formed Jesse Lasky Feature Play Company. Within two years Zukor and Lasky had merged, Zukor had kicked out W.W. Hodkinson who’d founded Paramount, and set out to take over the industry with a vertically integrated company that produced, distributed, and exhibited films , . Zukor attempted to buy up the major theater in every significant city in the United States, and if rebuffed, would build, or threaten to build, a bigger and more opulent house across the street. This led to competition from exhibitors who formed their own production and distribution company, First National ; William Fox formed a similar vertically integrated company while other newcomers specialized in only one or two of the three areas. All spent heavily on spectacular flagship theaters in major cities in which to open their films. This was encouraged by a significant change in audience demographics in the United States, where the prestige presentation of longer features in legitimate theaters and the newly constructed “picture palaces” removed the stench of the blue-collar nickelodeons for the middle and upper classes. However, the shift from one @10-15 minute film a day to two @one-hour long films a week, Paramount’s approximate annual quota from 1917 until the start of sound, did not lead to better stories, which would have been impossible with so many companies turning out an equal number of films. Plot synopses from this period, quoted in a number of sources, reflect the increasing “if you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all” nature of most of the films . Later producer and educator Kenneth MacGowan, an early film critic in Philadelphia from 1915 to 1917, observed that while he exalted the potential of the medium, he deplored “’the crude plots, the ugly crime, and the silly happiness…the disjointed mediocrity’ that filled and dominated the screen.” Yet this did not seem to bother audiences who were being brought new dramatized stories every week in parts of the country that had never seen a stage production, much less had new ones coming in every few months. . The increasing construction of theaters devoted exclusively to motion pictures around the country aided this . Motion pictures were the first true mass medium, and by the end of World War I they had become the most popular form of entertainment in the country. But within two years of the end of the war American audiences seemed to be increasingly taking movies for granted and were turning their attention to other diversions, especially those that hadn’t been available before the war, a situation that would reoccur 25 years later following World War II. Over the previous century, major conflicts had been followed by periods of affluence for the victors and a vision of new scientific discoveries that would lead toward a Utopian future. The already begun Industrial Revolution exploded after the Civil War and there were yearly expositions around the country at which new inventions, including, as noted, early attempts at motion pictures, were displayed. World War I essentially nailed the lid on the 19th Century, especially in the United States, and a combination of factors initiated the radical change in American life that would lead to the “Jazz Age”: the social movement from a blue collar agrarian/manufacturing economy to a white collar one, from a bucolic/small town oriented society to an increasingly urban oriented one, the trend toward at least a high school education for all classes, and most significantly, increasing access to personal mobility via the automobile. And in 1921, along came radio. William Fox claimed that he was stimulated to explore the possibilities of sound films after noting that before 1921 theater attendance was better on rainy nights, but this changed after the introduction of radio. In 1922, the industry saw a drop-off in attendance, not as significant as during the 1919 flu epidemic, but enough to stimulate interest in recovering that lost audience. Like Fox, the Warner Brothers, attempting to challenge the supremacy of Paramount, and MGM, which would become Zukor’s most serious rival after the 1924 merger of two struggling companies, would investigate ongoing experiments to add sound to films. Color was also considered, and though adding simulations of it by tinting the base and toning the silver of prints became a standard procedure for almost all films of the Twenties , the limitations of original photography in two-color Technicolor and similar processes was found wanting. Following the sleeper success of The Four Horsemen Of The Apocalypse (Metro; 1921), a film about the recent war being considered box office poison before its release, various companies embarked on a series of big budget spectacles: The Covered Wagon and The Ten Commandments (Paramount; 1923), The Hunchback Of Notre Dame (Universal; 1923), The Iron Horse (Fox; 1924), and the biggest of them all, at the time, Ben-Hur (Metro-Goldwyn; 1925). And those companies that owned theaters embarked on building even more opulent “picture palaces” in which to show them. This increase in the size of theaters naturally affected the size of the screen and the image projected thereon. The typical 200 seat nickelodeon was about 25 ft. wide, 70-100 ft. long and had screens averaging 10 to 15 ft wide . Nickelodeons with 500 seats and a pit for a 10 piece orchestra had 24 x 18 ft. screens . Improvements in print and negative stocks, projection lenses, and illumination made it possible to project images up to this size without sacrificing quality . Screen size did not change with the building of movie palaces accommodating 3,000 to 6,000 patrons as increasing the image size would stretch the limits of the presentation train as well as the amount of illumination it was safe to subject to the volatile nitrate film. John Belton has commented on the irony of the picture seeming to get smaller as the theaters got larger . Additionally, fire laws required that the projection booth be behind, and a certain distance above, the last row of seats in the highest balcony, which also meant projecting the film at a somewhat steep angle, often corrected by tipping the top of the screen back slightly. The throw from the booth to the comparably tiny screen in many of these theaters was between 150 and 175 ft.! In 1930, the Society of Motion Picture Engineers’ Standards and Nomenclature Committee reported: “the magnification has already been pushed close to the limit set by the graininess of the film and its unsteadiness in the projector,” making “the projection of pictures of even moderate screen dimensions not altogether satisfactory.” Increasing the picture size was also limited by the balcony overhang, a taller screen would cut off the top of the screen for those in the back of the first floor. As Zukor supposedly put it when he couldn’t see the top of the screen from those seats at a demonstration of Magnascope, “That’s $300 we lose at every full house.” In theory, a wider image would solve this problem but no one in the industry seems to have seriously considered it at that time, though the potential was suggested by D.W. Griffith’s masking off the top and bottom of scenes involving action in a horizontal direction in Intolerance (1916); the idea was no doubt offset by his use of vertical and other masks for other scenes in the film. That these problems were being considered on the theoretical and experimental level is reflected in the Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, founded in 1916 by C. Francis Jenkins, who had been involved with Thomas Armat in the development of his projector. Jenkins organized the Society along the lines of the type of European professional scientific organizations at which had been presented many of the papers and experiments from which the motion picture would ultimately evolve. At biennial meetings held in various cities in the United States and Canada, the technical state of the four phases of the industry: production, post-production (editing, laboratory practices, and later sound), distribution, and exhibition would be gauged, papers read on specific relevant topics, and new products described and/or demonstrated, all reported on in a similarly biennial, later monthly, publication. While there was only one specific transaction dealing with Wide Film prior to 1929, the SMPE would become significantly involved with later developments, since many of those involved in those developments were members. After its formation in 1927, members of the Technical branch of the Academy Of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences would similarly be involved; of course there was an overlapping of membership from Hollywood and New York. |

|

Renewed interest in presenting larger, wider images | |

|

In the mid-teens however, what experimentation with photographing and

projecting wider images that has been officially documented was being done

by independent tinkerers outside the developing studio system. Press

releases on the systems officially presented to the public before 1929

implied a desire to better duplicate human vision in theatrical film

presentation, as was noted in this 1921 ad for one of these systems: “It is generally understood that one of the greatest drawbacks to the motion picture industry is the confined vision. The single lens camera takes a picture of about 30 degrees visual angle, while the eyes have a visual angle of about 65 degrees. Thus it will be seen that a man seated in a theatre close to a screen showing a full size picture, as the camera was to the object photographed when the picture was taken, has his vision restricted at least 50 per cent.” The earliest documented 20th Century experiments with a wider film/frame were those of Italian producer/inventor Filoteo Alberini, who was fascinated by the head and torso medium shots being used increasingly in American films, but wanted to place this intimate view of actors against a fuller and wider background . His idea was to adapt to motion pictures the principal of the pivoting lens, a “normal” focal length lens that moved across a wide aperture during exposure to get a wider field of view, one of at least 60 degrees . He supposedly began his work in 1910 and received British patent 29,875 for “Improvements in Apparatus for Taking Kinematographic Photograms”, filed for on December 29, 1913 and granted May 28, 1914, though there may have been other filings elsewhere in Europe. This was a general conceptual patent that implied the use of a negative wider than 35mm, though none was specified in the patent. World War I no doubt forestalled further development and it was not officially presented until 1922, when the process, called Panoramica , was demonstrated with a 23 x 58mm frame on a 5 perf 70mm negative and print, yielding a 2.52:1 aspect ratio. A film in the process, Il Sacco di Roma, was shown in 1923, though no reviews or comments on the process have been found .. The problems that probably doomed that version of Panoramica are illustrated by the experiences of Martin Hart of widescreenmuseum.com., who was fascinated with the idea of adapting the pivoting lens of the Widelux still camera of a later period to a single lens version of Cinerama. This camera used such a lens to shoot an undistorted 150 degree still image on 35mm film, but Hart noted: “First I couldn't figure out how to make a shutter that would close while the lens spun back to its starting point. The second problem was that a high speed exposure, far faster than normally used in motion pictures, is needed to freeze all movement in the picture at virtually the same instant. Without doing this, objects passing in front of the camera and moving in the direction of the lens rotation will become elongated while objects moving across the frame in the other direction become squeezed. If the camera was moving forward you would see a slight elongation of objects on one side of the frame and slight squeezing on the other.” Another attempt that appeared at this time was Widescope. George W. Bingham’s initial patent described a system in which images from three synchronized 35mm cameras were printed onto a wide film, his next for the use of three synchronized 35mm projectors to show prints from the three negatives with the intention of giving “panoramic or cycloramic views of very wide angle”. He was aiming for a total 60 degree field-of-view, and the patent filing also noted “the various usings may be adjusted with respect to each other in the accomplishment of a perfect joinder of view sections so that no line of demarcation can be distinguished between them with the result that a well defined and smooth appearing composite view is obtained.” This sounds a lot like Cinerama, on which work was begun in the mid-Thirties! However Bingham’s process proved impractical and was replaced by a camera with side-by-side 35mm movements and two lenses stacked one above the other that each photographed half the view. Each view was then printed onto a separate film and the theater’s two projectors were to be used for exhibition . . This camera was patented by John D. Elms, the patent assigned to the WideScope Camera Company, as Bingham’s had been. A 1921 ad for this version of the process proclaimed: “The WIDESCOPE CAMERA just doubles the angle of vision and thereby eliminates all danger of eye strain or cramped eye muscles. Every picture taken is in effect close up view. The WIDESCOPE CAMERA has particular advantages in the photographing of moving street scenes, military and naval maneuvers, extended landscapes, sports, entire stage scenes and the many widescope objects of special interest to moving picture audiences which are so extensive in area as to be photographable by the present cameras only from a distance, thus reducing the size of the objects and diminishing the details. The WIDESCOPE CAMERA employs standard film, requires no special manipulation or treatment and can be used with one or two films (either of which may be used in any standard projector), thus embodying the features of the ordinary camera with the additional extraordinary features possessed by no other camera.” Elms demonstrated this version of the process to the SMPE at their May 7-10, 1923 meeting in Atlantic City, NJ. , the first Wide Film presentation to them. However, it was also found to be impractical and was then changed to a process using a single 57mm negative. On November 9, 1926 a two reel film in that version of the process, photographed by the legendary Billy Bitzer and Robert Greathouse began a commercial run at New York’s Cameo Theater under the name Natural Vision Pictures. A press release issued at the time of the screening stated: “This series of pictures was obtained through a process perfected by John Elms after nine years of effort. He first attempted to synchronize three cameras to obtain pictures of the width and height of the present ‘natural vision’. This failed and he tried two cameras, which also proved unsuccessful. Finally by means of a series of lenses and prisms in a single camera he has obtained the effect he wanted. “The film is twice the width of the ordinary strip of film, and the ‘frame’ is 25 per cent higher than the picture on the standard film. It was explained by a representative of the process that by means of an attachment that costs only a nominal sum the wide-vision pictures can be projected in any theatre. To take them, however, the special camera is necessary.” After extensively studying available information on this version of the process, Daniel J. Sherlock has surmised: “It would appear from the patents, frame sample and other evidence that the ‘twice the width’ film was in fact ‘twice the field of view’ and was 57mm, not 70mm. My guess from what I have seen is that the 57mm film was optically printed to two 35mm films and projected with two interlocked projectors”. Though not mentioned after this presentation, this version may have been the foundation of a 56mm “Natural Vision Pictures” system announced in 1930, with which Bitzer was also associated. Concurrent with this, Elms was also working on a pivoting lens approach like Panoramico. In 1924 and 1925 Walter McInnis filed for patents for a “swept lens” camera, which took a while to be published, in 1928 and 1931, and Elms added three patents to that approach as well, filed in 1927, 1928, and 1931, and published in 1930, 1931, and 1934. In August, 1927, as it will be noted, the Fox Film Corporation bought the rights to this version of the process and financed work toward improving it as an alternative to its own Grandeur process. Carl Louis Gregory summed up Widescope in his S.M.P.E. paper as follows: “Widescope first sponsored a double frame picture on standard film with the film travel horizontal instead of vertical; after that an Italian patent was acquired in which a wide film of about 21% inches width is held in cylindrical form about the axis of rotation of a revolving lens so that the succeeding frames are photographed on the same principle as in a panoramic still camera. Unfortunately this method of taking pictures introduces the same curvelinear distortion often noticed in circuit and other panoramic still photographs.” The other experimental wide film process from this period was the Spoor-Berggren process, named after credited developers George K. Spoor and P. John Berggren , Spoor’s chief technician . It had interesting roots thirty years earlier in the pioneering days of film projection. According to Ramsaye, Spoor, then a theatrical promoter, invested in a projector being developed by Edwin Hill Amet of Waukegan, Illinois which later was involved in the Edison patent wars. Spoor subsequently became an exhibitor and distributor in the Midwest and in 1907 formed the Essanay Company with G.M. “Bronco Billy” Anderson to make a series of one and later two reel westerns, first in Colorado, then in Niles in Northern California. Spoor was apparently also responsible for Bell & Howell’s work in standardizing film slitters, perforators, and camera and projector movements when he asked them to fix problems with such equipment that he had purchased from England . In 1915 Essanay scored a coup by hiring the increasingly popular Charlie Chaplin from Mack Sennett, but let him go a year later during an internecine battle between Spoor and Anderson, with the former buying out the latter and investing his profits in Chicago lakeshore real estate. Spoor did continue his motion picture interests, joining with other former Trust members Kleine, Edison, and Selig in a short-lived company called K.E.S.E., and, according to James L. Limbacher, in 1916, Essanay’s Chicago studios were closed to work on a new widescreen technique that took seven years to be worthy of public unveiling. Spoor claims that he was inspired to embark on his research after noting in the mid-teens that theaters were getting bigger, but screens were not. . The decision to go for a wider frame, rather than an overall enlargement of the image, likely stemmed from a desire to better fit the image into the wide legitimate theater type prosceniums then being incorporated into first run movie palaces, a point made by almost all proponents of wide film in 1929-30. Unfortunately there seems to be very little accurate information about the development of this process, especially earlier versions, because the first patents were not applied for until Dec. 20, 1928 , and that for a later version of the system. There is some debate as to whether or not the earlier camera used a negative larger than 35mm. A March, 1924 newspaper item claimed Spoor was to start a film called Price of the Prairie, using a negative described as being “three times the area of that used since the beginning of motion pictures” as well as being three-dimensional, but production had to be halted because they did not have enough lights to satisfactorily illuminate the sets. It is not clear from surviving photographs of the camera from this period whether or not a larger negative was used, or how many lenses it had. One such photograph suggests it employed two lenses side-by-side to record a “panoramic” image like Widescope without infringing on their stacked lens patents, which was the claim being made for it when it was first publicly announced in 1923 ; several 1929-30 articles on the process repeat this claim. Spoor supposedly started to shoot another film called The American around Christmas, 1926, directed by film pioneer J. Stuart Blackton and starring Charles Ray and Bessie Love. (Three-D was also claimed for The American in this deceptive quote: “Production Will Be First to Combine Natural Vision Photography with Stereoscopic Projection” .). But an article published a month later states that “Spoor explained this week that the story, ‘The American,’ has also been discarded. That story had been suggested to Blackton several years ago by Theodore Roosevelt as a series of historical incidents of the West. The story replacing ‘The American’ is yet unnamed, but is a human interest story of a small town during the period immediately following the armistice.” . It’s possible that the making of this film revealed major flaws in the process and apparently led to a redesign. |

|

Official public presentation with Magnascope | |

|

Although a press release on the Wide Film process Paramount announced in

1929 claimed that Adolph Zukor, like George Spoor, had been interested in

using a larger or wider film as early as 1914 , both studios’ serious

interest in a wider film stock and a wider frame may have been stimulated by

two occurrences on either side of the 1927 new year. The second was that

press release on The American and the Spoor-Berggren process, which

mentioned its use of wider film. A month later, another item noted that

projectors for the process were to be installed in the about to open Roxy

Theater in New York, then the biggest theater in the United States. (a

subsequent article about the theater’s projection booth, written after its

opening, does not mention these projectors). Though not large, the Film

Daily’s versions of the articles were on the issues’ front pages, just under

the headlines, so it was likely to attract some eyes, especially those who

had seen Magnascope. This was the first technique for presenting a “larger” image to be publicly shown under the auspices of a major film company, Paramount . Contrary to claims that have appeared elsewhere, there was no such thing as a Magnascope lens, though variable focal length lenses would subsequently be applied to it. The technique itself simply involved the use of a shorter focal length lens than that normally used in a given theater to show the larger image on a larger screen. As Harry Rubin, who has been credited as inventing such a lens put it: “It should be clearly understood that no claim is made that any new engineering principle is involved or that any radical mechanical advance has been made in the development of the Magnascope. When a 7-inch lens is used to secure a picture 18 feet in width, and it is desired to secure a picture twice this width, a 3 1/2 inch lens is necessary.” The idea was first demonstrated by Lewis M. Townsend and William W. Hennessy at the Eastman Theater, Rochester, NY on Feb. 15, and again in May and October, 1925, and August, 1926. Sequences from The Iron Horse (Fox; 1924) and North of ’36 and The Thundering Herd (both Paramount; 1925), as well as a complete presentation of The Black Pirate (United Artists; 1926) were used in these demonstrations . The presenters were unhappy with later publicity for Magnascope that claimed the technique originated with the presentation of Old Ironsides (Paramount; 1926). Glendon Allvine, a Paramount publicist at the time, takes credit for that first official use in that film’s roadshow engagement, which began at New York’s Rivoli Theater in November, 1926. According to Allvine, he’d been asked by Paramount vice-president Jesse Lasky to come up with a way of attracting audiences to the $2,000,000 production. Allvine remembered that “Laurence” (sic) Del Riccio, while seeking a job at Paramount six months earlier, had mentioned a wide angle lens in the Bausch & Lomb catalog that could throw a big picture on outdoor screens. It occurred to Allvine that this lens could be used for an audience participation effect that would create crowd-drawing buzz by putting the special lens and a selected sequence on a separate projector. At the moment of changeover, the screen masking would be moved back to reveal the larger screen, increasing the image size from 18 x 12 ft. to 40 x 30 ft. when the curtains had were fully parted and raised . He allowed no publicity prior to the first public presentation, which was enthusiastically received, according to this New York Times clipping he reproduced: “The scene that ended the first half of the picture was a startling surprise, for the standard screen disappeared and the whole stage, from proscenium arch to the boards, was filled with a moving picture of Old Ironsides. This brought every man and woman in the audience to their feet. Following the intermission, most of the scenes of Old Ironsides were depicted by this apparatus, a device discovered by Glen Allvine of the Famous Players Lasky Corporation. Mr. All-vine said that he called the idea or invention a magnascope. It is a magnifying lens attached to the ordinary projection machine. This wide angle lens was extremely effective.” Future use followed this approach of starting the Magnascope presentation with a subject coming toward the camera, for example the elephant stampede in Chang and the big aerial assault in Wings (both Paramount; 1927), and could be just as effective when going back to the normal size screen with an equally appropriate one, such as with the jaws of the whale closing down on Captain Ahab in Moby Dick (Warner Bros.; 1930) . Despite the fact that the Magnascope image was dimmer, grainier, and not as sharp as the regular program, the technique became popular enough for Simplex to make a Magnascope version of its projector with a 72 degree intermittent shutter to allow more light on the screen . On January 24, 1927 U.S. Patent 1,646,855, “Motion Picture Exhibiting” was filed by Lorenzo del Riccio of Paramount. The patent does not refer to any special lens but to “motion picture exhibiting and more particularly it is concerned with a system of exhibiting motion pictures which permits of varying size of the projected images of the film on the screen whereby certain novel effects are produced.” It was issued on October 25, 1927, but MGM, for one, got around it with its “Fantom Screen”, developed by a team of engineers including Joseph Vogel and J.J. McCarthy and introduced the following year for New York’s Astor Theater’s run of The Trail of ’98 which began on March 20, 1928. There is some debate as to whether the screen was mounted on rollers and moved toward the audience , or used a variable focal length lens. The use of a moving screen was confirmed in a SMPE progress report mentioned in a 1930 issue of Exhbitors Herald World. It was quite common for silent film prints to be reedited to suit specific exhibition situations and this was often done to enhance the Magnascope presentations. (Allvine had done this with Old Ironsides, ordering outtakes from the Hollywood studio and moving the ship launching sequence from the beginning to just before the intermission, a violation of production head B.P. Schulberg’s final editing rights that would ultimately get him fired. ) This could not be done with sound films, but the introduction of variable focal length lenses came to the rescue , though it is not clear how many theaters actually used them, especially in the United States. Del Riccio has often been erroneously credited as having developed an early zoom lens for Magnascope in 1924 , but Grant Lobban lists the Busch Vario-Kino lens introduced in 1928 as the first . It had a range of 70-140mm with three moving elements operated by a sliding sleeve. The projector-to-screen distance was set by a focusing ring on the front of the lens and was touted as always being in dead focus. Taylor Hobson then came out with a 3 in.-5-1/4 in. lens with the change made by rotating handles protruding from the barrel of the lens . As the Depression advanced, many American theaters dropped the regular use of gimmicks like Magnascope, but a handful around the country that had larger screens would revive the technique to enhance spectacular sequences in certain films for the next twenty years. The New York Times review of The Rainbow Trail (Fox; 1932) mentions that portions of it were shown on an “enlarged screen” in its first run engagement at the Roxy Theater . Claims have also been made of other select theaters using Magnascope for the jungle scenes and climax of King Kong (RKO; 1933), the Salt Flats chase in Stagecoach (United Artists; 1939), the burning of Atlanta in Gone With The Wind (Selznick/MGM; 1939), the orphanage fire in Mighty Joe Young (RKO; 1949), and the climax of Niagara (20th Century-Fox; 1953). It is not known whether these presentations involved a zoom lens or just a shorter focal length lens on one of the projectors. The relevant sequences of Kong and Joe were edited in such a way as to allow for the latter presentation . David O. Selznick is on record with regard to his revival of the technique, advertised as “Cycloramic Screen” for the hurricane sequence in Portrait Of Jennie (1949): “The situation on Portrait of Jennie was that I had argued with many people in the business that one answer to television was a very much larger size screen in théatres and suggested a return to the previous “Grandeur” and “Magnascope” effects. When Portrait of Jennie was finished, I decided to put this into effect with the last reel, containing the hurricane sequence. We learned that there were a. number of the large screens still in existence, and introduced the big screen. to this era of exhibition with Portrait of Jennie at the Carthay Circle here and at the Rivoli Theatre, New York. The results were superb: Jennie did the best business that had been done at the Carthay Circle for well over a year and had an extremely successfu1 engagement at the Rivoli. But I ran into all sorts of resistance from my own distributing heads, who felt that the expense of getting enough equipment for a national release was not warranted, and also from exhibitors. In consequence, we limited this treatment of Jennie to the handful of theatres that could be accommodated with equipment already in existence, and with a few additional pieces of equipment that we had made up at our own expense and routed through several theatres. Their judgement was wrong: the results on Portrait of Jennie without this big screen effect were not remotely comparable with those in the theatres in which we conducted the experiments.... What effect this experiment had upon the introduction of. CinemaScope and the other big screen processes, if any, I have no way of knowing.” A proposed attempt to capitalize on the interest in “wide film” in 1930 was essentially a variation of Magnascope with the top-and-bottom masked off. It was from a newly formed B-picture company called Liberty Pictures, who claimed exhibitors need only install a wide screen and a shorter focal length projector lens to show their upcoming films wide. Grant Lobban describes a similar use of zoom projection lenses and larger screens in England in the early Thirties. Here, often because of problems with existing prosceniums, only the width could be increased, resulting in expanded images closer to those achieved with the American wide film processes. According to retired English projectionist Robert Floyd, a reduction print from the 65mm negative of The Bat Whispers (United Artists; 1930) was shown this way at London’s Regal Cinema in 1931. United Artists supplied the lenses and special aperture plates to show the film on the theater’s Magnascope screen, and UA part owners Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, who were visiting London at the time, dropped by to see how it looked. . The Magnascope technique soon fell into disfavor in England due to indiscriminate use by exhibitors. It was relegated to portions of newsreels and novelties, though even this use wasn’t that popular, as noted in this comment from the October, 1933 issue of The Talkie Magazine quoted by Lobban: “The wide screen used for the news bulletins and sundry trifles in the West End at the present is one of the silliest “kids” the cinema public has had put over on them. The general appearance is that the film is twice as broad, remaining the same height, and that a panoramic view is consequently obtained. The mere facts of the matter are that in the magnification of the film to twice its breadth it is also magnified to twice its height, and to get this on the screen the top and the bottom of the screen have to be cut off. Instead of seeing twice as much scene, therefore, one only sees half the amount which means that the “wide-film” is just defeating its own ends. On top of this, the larger spread is to the detriment of clarity. The wide screen is quite alright for organ recital illustrations or fancy trifles, but for news bulletins I fail to see the object". So far no evidence has been presented of the Magnascope technique used in any other countries but the United States and England. |

|

William Fox and the actual advent of Wide Film | |

|

According to Glendon Allvine, William Fox and his vice president and general

manager Winfield R. Sheehan saw Magnascope at the Rivoli. on Dec. 7, 1926 ,

and though impressed, were very much aware of its technical flaws. Fox had

retained Earl I. Sponable, who’d worked with Theodore W. Case in developing

the Movietone sound-on-film system Fox had licensed, to set up a research

department, not only to improve Movietone, but also to keep abreast of

technological developments that might be beneficial to the company. At some

point in 1927, Fox personally began financing Sponable’s secret work on

developing a new wide film process. As part of that research, Sponable

naturally checked out previous work that had been done. A memo Sponable

wrote on June 24, 1932 detailing the development of what would come to be

known as Grandeur mentions one such process that was given serious

consideration: Aug 13, 1927 …a showing of WideScope pictures to various people of the Fox Film Corporation …confirmed my judgment that the Widescope camera as it then existed was impractical for making studio pictures due to the loss or light in panoramming the lens and the inertia on the moving parts. …Regardless of this Mr. Smith made an agreement with Mr. Elms for Mr. Fox, paying $25,000 for the invention, contract to run for ten years, Elms to get 5% interest in the pictures plus salary for himself. After completing this deal Mr. Smith assigned me to take charge of the development of wide pictures and give Mr. Elms every facility at our disposal for perfecting his camera. For this extra work I was promised $15,000 and as much stock in the wide film company as Mr. Waddell would receive. Work was immediately started to develop equipment that would combine sound with the wide pictures. Mr. Elms, Sr. chose to build a camera in a small job shop of Stoeger & Company, 94 E. 10th Street, New York City, without design work or drawings and few tools to work with. This was started in September, 1927. Some sample pictures were made in February, 1928. The job was never practically completed and cost $3,505.17. Oct. 7, 1927 The attached copy of memorandum written by Mr. Smith mentions that all Widescope charges are to be paid by Mr. Fox personally. The following entry in this memo suggest that the name had been chosen and work was already progressing on what would become Grandeur: Oct., 1927 The attached copy of memorandum from Mr. Smith to Mr. Wm. Fox gives the status of the Grandeur program and may be of interest. As does this passage in a letter Sunrise director F.W. Murnau wrote to William Fox at the end of 1927, in which he “inquired about the possible use of the wide-screen 70mm process Fox was developing for use in a picture he was already planning to make in the coming summer. The tentative title was Our Daily Bread : “‘A story that will tell a tale about ‘WHEAT’ - about the ‘sacredness of ‘bread’- about the estrangement of the modern metropolitans from and their ignorance about - Nature’s sources of sustenance, the story adhering to the stage play The Mud Turtle. I believe that this theme would be a great starting vehicle for the Grandeur Film.’ ”. Meanwhile, another development associated with the introduction of sound, and Fox’s specific involvement therein, also created a climate that was potentially receptive to the introduction of a new film format. While sound-on-disc systems retained the full aperture 1.33:1 silent frame, in his experiments, Lee De Forest had placed his optical track along its left side, inside the perforations. Case and Sponable had followed this approach when they developed their variable density system and, for the sake of compatibility, it became the unofficial standard for other developers of sound-on-film systems, such as RCA with its variable area Photophone track. The approximately 100 mil. devoted to the track shaved the existing picture aspect ratio to @1.15:1 , which appeared taller than square on the screen , especially in theaters with steep angles of projection, and necessitated two sets of aperture plates and adjustable masking for theaters which used both sound-on-film and sound-on-disc. . By early 1929 some first run theaters had their aperture plates for sound-on-film cut with reduced height to return to the 1.33:1 ratio and used shorter focal length lenses to project this image onto the same size screen used for sound-on-disc films, though this cut off heads and feet in full shots, and resulted in grainier and not-as-sharp pictures. (Until mid-1930, only Warner Bros.-First National distributed its films exclusively with sound-on-disc; other companies either varied between the two formats or released films both ways, as well as silent versions with title cards.) Also, despite differing sound recording and playback systems, everybody had to pay license fees and royalties to AT&T for the amplification equipment. This further stimulated William Fox’s interest in developing a new format: to set some kind of new standard for the industry for which everyone would have to pay him royalties. Although the media conglomerate that is the successor of the company he founded is now primarily known by his last name, William Fox himself is the forgotten man of film history as is much of the history of the company before it was merged with Darryl F. Zanuck and Joseph M. Schenck’s 20th Century Pictures in 1935. The latter is due in part to most of its silent films being lost and the surviving pre-merger films rarely being shown, but in the former instance because, after making a major contribution to the development of the industry, Fox appears to have kept a low profile until about 1926. Unlike Louis B. Mayer or Jack Warner, he was uninterested in personal celebrity, once telling a publicity man, “This mug of mine will never sell any tickets, so just concentrate on getting the stars into magazines and newspapers and forget about me.” This is strange considering that in a business run by megalomaniacs, Fox was perhaps the biggest of them all, with a voracious appetite for power that would ultimately lead to his downfall. (Fox would occasionally appear in the company’s newsreels with dignitaries, also in a clip showing his golfing skill with an arm permanently crippled in a childhood accident.) There appears to be no really objective image of William Fox like that of his contemporaries Carl Laemmle and Adolph Zukor. Allvine claims his interaction with Fox was mostly positive, but that’s the exception; neither Alexander Walker or Scott Eyman, writing about his involvement in the introduction of sound, could find any positive comments about him personally. The most revealing portrait of the Fox of the late Twenties and early Thirties comes from Upton Sinclair in his introduction to his book on him. Sinclair had built his reputation on a series of muckraking books on small businessmen destroyed by big banks and Wall Street. In 1933, at a party in the home of a screenwriter friend, he was asked why he was wasting time writing books on men worth $150,000 being ruined when he could do one on a man worth $50,000,000 in a similar situation: William Fox. The very next day Sinclair got a call from Fox requesting an interview for such a book. When Sinclair didn’t seem interested, Fox showed up at his home the following day and poured out a tale of woe that changed his mind. Unfortunately Sinclair accepted Fox’s version of his then ongoing downfall without getting any counterbalancing comments from others. Like Paramount’s Zukor and Universal’s Carl Laemmle, Fox was a poor Jewish immigrant from Eastern Europe who prospered in the clothing business and invested his profits first in nickelodeons, then in his own exchange, The Greater New York Rental Company. When the Trust was formed and approached him about acquiring his exchange, he would have sold out if it had met his price. When it didn’t, he capitalized on President Theodore Roosevelt’s campaign against other big business trusts by bringing a series of lawsuits against it, which ultimately broke it apart. In 1914, Fox went into production with a company first called Box Office Attractions, later the Fox Film Corporation. Initially working out of studios in New Jersey, in 1917 he began West Coast production at what had been the Selig Studio in Edendale near Mack Sennett’s, with operations put in the hands of his chief lieutenant Winfield “Winney” Sheehan, a refugee from the criminal activities of New York City’s Tammany Hall. The following year he bought a studio that had been built on both sides of the southern corner of Sunset and Western and had previously been owned by Thomas Dixon, author of the novel The Clansman that was the basis for D.W. Griffith’s The Birth Of A Nation (Epoch; 1915). . The main historical significance of the Fox Film Corporation for the next decade was its stars, Theda Bara and Tom Mix, and in giving impetus to the directing careers of Raoul Walsh and John Ford. He also began building first, a national, then an international theater chain. In the mid-Twenties Fox bought a plot of land southwest of Beverly Hills on which, after his purchase of the Theodore Case sound process, he would build the first studio specifically designed for making sound films. According to plot synopses in various publications, notably the American Film Institute’s Catalogs for the Teens and Twenties and in filmographies in other publications, the bulk of the Fox films made between 1914 and 1925 were on a par with Universal’s: simplistic bucolics aimed at small towns, as opposed to the increasingly sophisticated urban oriented fare being done by Paramount and the two major rivals to it that emerged in the mid-Twenties, MGM and Warner Bros. (In 1921, theater magnate Marcus Loew had purchased the struggling Metro Film Company and when its fortunes hadn’t improved by 1924, had negotiated a merger with the equally struggling Goldwyn Pictures and brought in efficient independent producer Louis B. Mayer to run the new combine. The result was the first company to successfully challenge Zukor’s supremacy, followed very closely by the upstart Warners, who’d gotten involved in exhibition in the nickelodeon days, distribution in 1914, and serious production in 1918.) According to early film historian Benjamin B. Hampton, Fox became aware of a drop-off in the popularity of his company’s films in the early Twenties , and 20th Century-Fox historian Aubrey Solomon documents his initial efforts to redress the situation. Scott Eyman dates those efforts to 1926. Earlier, he had begun expanding his theater holdings, especially in major cities, including what would become his flagship, New York’s Roxy, and announced that for the new season starting that September, “Fox takes another great step forward through the production of the world’s best plays and popular novels of high screen value.” In addition to the statements Fox made to Sinclair, Eyman states that the appeal of sound for him also stemmed from an interest in gimmicks that would attract more people to the boxoffice; his interest in Grandeur would have been in the same vein, but was also stimulated by press reports of early attempts at television. Like Warners, Fox had used his Movietone system to add music and sound effects to silent features, but he’d also made sound shorts and started a newsreel, which had had the good fortune of filming, and recording, Lindbergh’s take-off, and triumphal parade in New York. However, Fox appears to have been as blind to the prospects of “talking” features as Warners. Dialog sequences did not begin appearing in Fox films until late summer, 1928, and then only sporadically for the rest of the year, supposedly because they were continually improving their recording techniques, while Warners and other studios were putting dialogue scenes in practically everything they were releasing. But Fox’s first all-talking feature was a major breakthrough for sound films: In Old Arizona, shot primarily on location using a Movietone newsreel sound truck, and released at the end of the year. Curiously, contrary to the accounts by Eyman, Walker, and other historians, the trade papers of the time, Film Daily, and Variety and Exhibitors Herald World, which were weeklies, were quite blasé about the advancing sound revolution. Film Daily’s review of The Jazz Singer not only does not mention any use of dialog in the film, but has no account of the first night audience reaction described by sound historians. They appear to have not taken sound seriously until mid-1928, when, after an increasing number of features with synchronized sound effects, music, and dialog sequences of increasingly greater length, there came the first “all-talking” feature, Warners’ Lights Of New York. After that, the sound vs. silent debate would continue through 1930, when Fox Film Corp. declared it would make no more silents and the other studios soon followed suit, though as late as 1931, small town exhibitors were still hoping silents would come back, according to letters from them printed in Exhibitors Herald World. Naturally there was no mention of any of the Wide Film experiments going on at that time. Fortunately we have the Sponable memo for an idea of what was happening at Fox: Jan.23, 1928 Realizing that the results with the Elms type camera would likely be impractical I started a regular news camera for Grandeur film, at the shop of the J.M. Wall Company. This was completed on February 6, 1929 and cost $7,000. Feb. 1, 1928 The Mitchell Camera Corporation was also requested to build a camera of standard Mitchell design, but adapted to use with Grandeur film. This camera was delivered August 6, 1928 and cost $12,040. The results of pictures made with this camera were satisfactory. Oct. 14, 1928 The second oscillating lens camera [WideScope] was started at the. J.M. Wall Machine Company under the direction of Chas. D. Elms, Jr. Work on this was carried on until August 8, 1929, and project abandoned. Cost over $8,000. November 1928 Mr. Fairbank came to the Fox Case Corporation and advised he was in position to promote a sale of the Mitchell Camera Corporation. Dec. 5, 1928 Grandeur equipment was transferred to the West Coast studios for the purpose of tests preliminary to making a feature picture. Dec. 7, 1928 Letter from W.G. Fairbank indicates E. I. Sponable leaving for Los Angeles to look over the Mitchell Camera Corporation in connection with the Fox deal. Dec. 23, l928 Three Grandeur Mitchell cameras were ordered like first sample delivered at a price of $1,500 each. Jan. 14, 1929 Letter from Harley L. Clarke to Courtland Smith containing notes referring to formation corporation to market and exploit WideScope projector. Some of the tests mentioned may have been done on the set of Hearts In Dixie; Kann, a columnist for Film Daily, refers to it as having been shot in Grandeur on January 16, 1929, but this is unlikely given the already dubious commercial potential for an all black cast film; the 35mm version was released about a month later and there was no mention of Grandeur in association with it. Also, there is no information on what Fox did with WideScope beyond the above descriptions of the process as it existed before they licensed it, and, as noted, experimentation was ultimately abandoned in August, 1929 when demonstrations of the other two processes in development gave Fox confidence that Grandeur was superior to them all. |

|

The effects of sound on Wide Film Developments | |

|

In the 1929 press release issued with the first demonstration of Paramount’s

wide film process, it was claimed that Lorenzo Del Riccio had been put to

work on developing the new process by Adolph Zukor “right after” the

launching of Magnascope. He was to eliminate the obvious flaws in the

technique with consideration of the balcony overhang problem and with

minimal changes in existing sound and projection equipment. The mandate for

“no changes in sound equipment” is unlikely if Del Riccio had actually begun

his work early in 1927. No more information has been found on Del Riccio’s

work between then and the official unveiling of his results. As noted with the Aug. 13, 1927 entry regarding WideScope, and given Earl Sponable’s background and William Fox’s involvement with sound and hopes for Grandeur, sound, especially sound-on-film, had naturally been part of that process’ initial design as well. Though all the studios but Fox, Warners/First National, and RKO initially experimented with both film and disc systems and, except for Warners/First National, made their films available in both formats through 1930 , only that studio and Educational Pictures, which made comedy shorts, were adamantly for sound-on-disc. A provision for a 100 mil. optical track like that on 35mm film was made for Magnafilm. It was apparently the Movietone/Western Electric variable density type, as that was the sound-on-film format licensed by Paramount. At some point in 1928 Spoor and Berggren decided improvements in their process were far enough along to consider adding sound to it. It’s not clear why they chose to approach RCA for this purpose beyond the fact that its system was cheaper than either Movietone or Vitaphone. The previous year, radio pioneer David Sarnoff, seeing a potential new market in sound films, had his engineers develop their own sound-on-film process, which they called “Photophone.” To promote his system, Sarnoff bought the small FBO Pictures company then owned by Joseph P. Kennedy and the Keith-Orpheum Theater chain and merged them into a new company called RKO (Radio-Keith-Orpheum) Radio Pictures (or Radio Pictures as it was known until 1937). Unfortunately, he was unsuccessful in selling the process to the other majors, and for the next decade low budget independent companies would be RCA’s primary other customers. For some reason, RCA chose not to put a track on the Spoor-Berggren film itself, but to use a double system format, essentially a film equivalent of Vitaphone, in which an RCA optical sound head was attached to the side of the projection head, both driven by the same motor. |

|

Wide Film Officially Goes Public | |

|

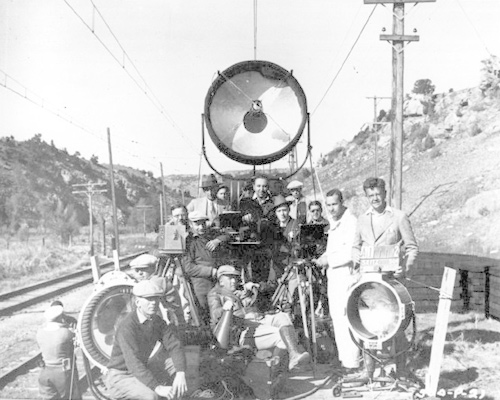

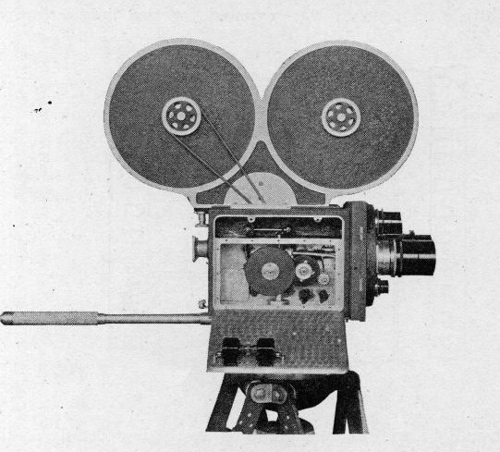

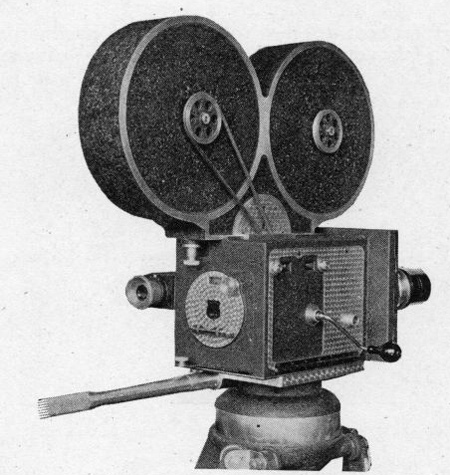

Although rumors about Wide Film developments began appearing at the

beginning on 1929, as noted with the item in Film Daily’s Kann’s column from

that time, apparently the first acknowledgement of it was in the April, 1929

issue of International Photographer, a publication of the Hollywood camera

local which had just elevated itself from a homey newsletter for members to

a serious technical periodical. It was an article entitled “70mm Film Versus

Other Sizes” by George A. Mitchell of Mitchell Camera and extolled the

virtues of the Grandeur camera his company had built for Fox versus the

other then rumored sizes and included photographs of the prototype camera

and its being used for tests at Fox’s New York Movietone studios. Mitchell

claimed that the camera was the basic Mitchell body with wider sprockets and