What is Todd-AO? |

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| From the "Oklahoma!" souvenir programme | Date: 01.07.2008 |

|

|

Further

in 70mm reading: |

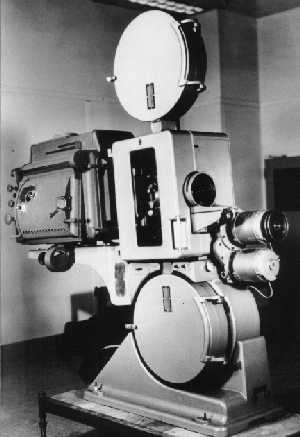

The Todd-AO “all-purpose” projector - built

by the N. V. Philips’ Gloeilampenfabrieken of Eindhoven, Netherlands - is only

slightly larger than a 35mm machine. The Todd-AO “all-purpose” projector - built

by the N. V. Philips’ Gloeilampenfabrieken of Eindhoven, Netherlands - is only

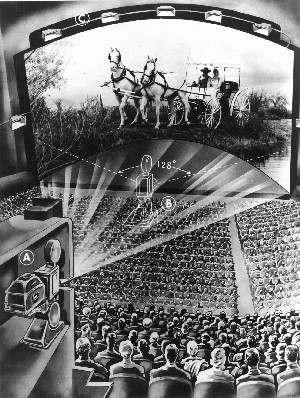

slightly larger than a 35mm machine. Once the lenses had been developed, the design of the camera followed naturally. But, to design a projector that could reproduce the perfection of the photography onto the screen was a separate problem. The new projector had to provide for film now 70mm wide, the extra 5mm carrying a six channel, high-fidelity, Orthosonic sound track developed by Fred S. Hynes of The Todd-AO Corporation (formerly of Westrex). The Todd-AO “all-purpose” projector - built by the N. V. Philips’ Gloeilampenfabrieken of Eindhoven, Netherlands - is only slightly larger than a 35mm machine. Yet, it will project film from any of the eight motion picture systems in use today! Angle of projection was the final problem and a new, complex system of optics was invented to solve it. Any standard method distorted the picture so much as to be unusable. The final result? In Dr. O’Brien’s words: “It is as though the picture were shown from a ‘phantom’ projector located ten or twenty feet over the heads of the audience in the forward orchestra seats of the theatre.” TODD-AO film, plus the TODD-AO camera, plus the TODD-AO “all-purpose” projector, plus TODD-AO Orthosonic sound, and the great, arced TODD-AO screen equal clarity of perspective, delineation, and color reproduction. But, most important with TODD-AO, audience participation now has its fullest expression. Most of us were brought up believing in the unpleasant little aphorism that the second occasion is never quite so enjoyable as the first. This could be the second glass of beer, the second kiss, or the second plunge into the lake on a hot day. If you had been fortunate enough to do OKLAHOMA! in 1942 and ‘43, you would hardly expect that doing it again in 1954 and ‘55 could be anything but a nuisance. Nothing could be further from the truth, and this is where the aphorism disintegrates. There was an excitement for us in doing OKLAHOMA! for the movies that was wonderful to experience. |

|

The Magic of Motion-Picture Techniques |

|

| It would be impossible to spend a whole summer

working with studio people without coming away deeply and permanently impressed

by the staggering nature of their techniques. Possibly, the confirmed Hollywood

studio man is not particularly impressed by the sight and sound of Gordon

MacRae singing way out in the country, on horseback, and accompanied by

a large symphony orchestra. Possibly some of you sitting in the motion-picture

theatre don’t care particularly how it was done either. But we cared

tremendously.

In our lives this little event was no more taken for granted than the first

trip of the atomic submarine Nautilus. We had this same orchestra in the studio one day to record one of the songs. The next day we listened to the recording and to our horror discovered that in the second bar of the refrain there was no B flat in the bass. Incredibly the B flat just had not been recorded. In our ignorance we though the whole orchestra would have to be called back and the song done all over again. But the head of the music-sound department, who was with us, explained this wasn’t necessary at all. The studio had a file of notes played by various instruments and they simply picked out a B flat for string bass and inserted it in the proper place on the sound track. |

|

Planning Oklahoma Skies in Arizona |

|

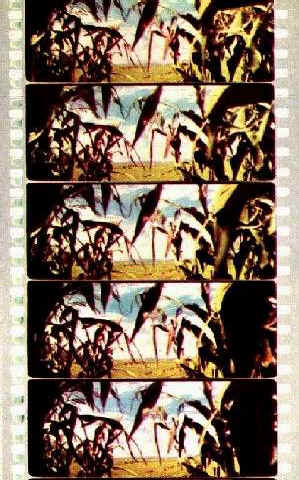

Perhaps the most exciting part of the whole job

was to go on location. Our particular area was up in the desert mountains

on the Mexican border of Arizona (instead of Oklahoma, to avoid anachronisms

in the landscape and because of technical considerations of production).

We chose a time when the skies of Arizona are alive with wondrous clouds,

which fall into the most startling formations and shapes. This happens

in what they call the rainy season, and it was the rainy season we chose,

having been assured that rain would fall only an hour or so every other

day, just enough to provide those clouds. Perhaps the most exciting part of the whole job

was to go on location. Our particular area was up in the desert mountains

on the Mexican border of Arizona (instead of Oklahoma, to avoid anachronisms

in the landscape and because of technical considerations of production).

We chose a time when the skies of Arizona are alive with wondrous clouds,

which fall into the most startling formations and shapes. This happens

in what they call the rainy season, and it was the rainy season we chose,

having been assured that rain would fall only an hour or so every other

day, just enough to provide those clouds.The forecasters were less than accurate. The rainfall was the heaviest the state had had in seventeen years. We paid dearly for those beautiful skies you will see in the picture. Everything would be going along fine on a nice sunny morning. The heavens would smile, and their smile would be photographed. Then suddenly Art Black, assistant director, would say, “Boys, here comes a goose drowner,” and the goose drowner - a black, angry cloud - could be seen, peering over a hill, ready to rush at us. Before we knew it, we were huddled in Aunt Eller’s farmhouse, waiting for it to pass. Sometimes this took the whole day and we would all go back to our hotels and motels, drenched to the skin. Flash floods would come roaring down the arroyos. One day a Cadillac was lifted up by one of these torrents and taken two miles away. It was recovered, but has not been the same since. Just the logistics alone of taking actors, light men, sound men, and all sorts of gear from Hollywood to our base of operations would have been enough to terrify anyone but a motion-picture man. An unbelievable number of drivers were required - drivers of trucks, camera trucks, sound trucks, busses, limousines, trailers. A large herd of cattle was hired, as well as cowboys and wranglers to control them. A train and locomotive of the period were procured. An old-fashioned railroad station was built to receive the train. Back in California they showed us the streamlined truck that would take the costumes to Arizona. It was enormous and quite handsome. The wardrobe women would have to work inside it, they explained to us, so it was air-conditioned. Most of our shooting took place 30 to 50 miles from Nogales. There must have been some pretty fancy wand-waving going on, because every day at 12 o’clock a very fine hot lunch appeared. The rain appeared just about the same time every day, and this was just about the only problem that seemed to faze the studio boys. Fifty miles from Nogales there are no cute little doors marked “He” and “She,” but even that was taken care of - chemical and portable. The farm on which Laurey and Aunt Eller live was built on a location that had been chosen more than a year before. No one, driving up to this farm, would have doubted that it had been lived in for many years. It had been carefully designed months ahead of construction. The corn was grown on a slope running down toward the road that passed the house. The house was set between two gigantic cottonwoods. A peach orchard was planted right next to the house. Then the bar, of course, and the windmill, and Jud’s smokehouse in a hollow. We had no idea that outdoor sets were as carefully designed as stage sets. There is a model of this farm in our offices in Hollywood, and the actual farm came out exactly as the model demanded in every detail. The corn had been planted in January, 1954, so that it would reach its fullest height in late July and early August. For a while it looked as if it wasn’t growing as fast as we had anticipated. This made us very anxious, because we are committed to that line, “The corn is as high as a elephant’s eye.” For a while it looked as if we might have to change the lyric and have Curly sing, “The corn is as low as an elephant’s toe.” But the rains came, and the sun came, and the corn grew; and when you see Curly ride by this corn in the picture it will be, we are sure, as tall as any corn you have ever seen. It looks as high as the eye of an elephant who is standing on another elephant. And it helps give the kind of sweep and bigness we want at the opening of the picture, when Curly sings, “Oh, What A Beautiful Mornin’!” Unwilling to trust our first child to anyone but ourselves, we have formed our own picture company and are presenting OKLAHOMA! When people ask us, “What are they doing with OKLAHOMA! in Hollywood?” we have to answer that there is no “they” in this case. If anything is wrong with the picture, don’t blame “them.” Blame us. We take full responsibility. This does not mean of course that we can yet call ourselves picture producers. The production was put in the charge of Arthur Hornblow, a talented producer of great and long experience, and Fred Zinnemann, who directed From Here To Eternity and High Noon. For many years, theatre people like ourselves have thought it fashionable to look down our noses at the synthetic procedure of picture making. Perhaps this is a good time to state that no art form exists that is not synthetic. The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel is a collection of figures, the Fifth Symphony of Beethoven is a collection of notes. The importance here is what these collections have to say. Whether or not the camera stops eighteen times during the filming of a given scene is of no importance whatsoever. The only thing that should interest us is what the finished scene has to tell. The art of motion pictures is a laboriously difficult one, but it is an art nevertheless when its basic materials are good and when they are expressed with talent and emotion. This is our prayer for the motion picture "Oklahoma!". |

|

| Go: back

- top - back issues

- news index Updated 21-01-24 |

|

Todd-AO is the perfected film process

that give you - the audience - a sense of participation in the action,

the feeling of presence in every scene.

Todd-AO is the perfected film process

that give you - the audience - a sense of participation in the action,

the feeling of presence in every scene.