The Importance of Panavision

|

This article first appeared in

|

|

Written

by: Adriaan Bijl, Holland Reprinted by permission from the writer and Panavision |

Issue 67 - March 2002 |

|

Panavision started delivering its attachments in March 1954 (1). Sales and distribution rights of the Super Panatar were held exclusively by Radiant Screen Corporation. The original price was $1100 a pair, but by July 1954 they were advertised at $895 a pair (2). This was considerably less than the Bausch and Lomb lenses, which were available at a minimum of $1095 a pair, probably the reason for the price-reduction of the Super Panatar (3). By the end of 1954, another reduction was announced: The retail price of the Super Panatar was established at $695 a pair (4). Between March and May 1954, over 300 pairs of Super Panatar attachments were sold and delivered worldwide (5). The price was one factor in its success, but there were others. On March 29th of that year, 20th Century-Fox officially declared their withdrawal from the marketing of anamorphic projection attachments. Apparently, there had been some confusion among exhibitors as to whether or not Fox approved their showing of Fox film product with the Super Panatar, or with other non-Fox equipment. Spyros Skouras, the president of Fox, even stressed "the great contribution of Robert Gottschalk's Panatar process in the perfection of variable projection" (6). This must have made quite an impression upon the confused exhibitor, mainly because Panavision was not the only company with a variable projection attachment. SuperScope, also an anamorphic taking and projection system, had been modified by Irving and Joseph Tushinsky by order of Howard Hughes, president of RKO pictures. Hughes did not want to pay a license fee to Fox, so he developed his own system for RKO. Due to patent rights, he couldn't make it exactly the same, however, so he therefore modified the image area on the filmstrip: A black border on the right side of the frame reduced the projected aspect ratio to 2:1. A normal Bausch and Lomb attachment could still be used during projection, since the expansion factor was still 2. Like Fox, the Tushinsky brothers apparently wanted a share of the theater market (7). Skouras mentioned SuperScope in his statement, but did not praise it like the Super Panatar, probably because it belonged to another studio, while Panavision was an independent company. The price of the SuperScope attachments was $700 a pair, considerably less than the Super Panatar. The support of Skouras, however, the man who had given the world CinemaScope, might have been an additional encouragement for the theater owners to buy the Super Panatar (8). Another reason for the success of the Super Panatar was support from MGM. This studio had tested the Super Panatar which resulted in an order of over 30 pairs by Loew's International, MGM's parent company (9). Due to the anti-trust legislation of 1948, all studios had to divorce themselves from their theaters in the US. But the Hollywood film companies still owned a number of theaters abroad, and that is where Loew's needed the Super Panatar (10). However, the projection attachment was not the company's only product at that time. Gottschalk had become acquainted with the head of the technical department of Columbia Pictures. In the beginning of 1954, this studio wanted a conversion printing device. Since not every theater was equipped with the required modifications for showing CinemaScope, every film had to be photographed in an anamorphic and a non-anamorphic, also known as "flat", version (11). There could be another way: Expand the printer, a device explained in Chapter 1, with a de-anamorphoser. In other words: during printing, the exposed negative of an anamorphic film could, by means of a converted printer, be transformed to a positive with a different ratio such as 1.85:1. Of course this meant chopping off the left and right edges of the wider anamorphic image, but it eliminated the cost of so-called double shooting with both anamorphic and flat camera lenses. The conversion process could also be reversed from non-anamorphic to anamorphic if, for example, library stock footage had to be inserted in an anamorphic film. Columbia was not the only company to install this so-called Micro Panatar. In 1954, Technicolor, Universal International, and MGM each ordered one as well. The purpose was the same: Avoid double shooting (12). In March 1955, one year after the Super Panatar was introduced, another projection attachment was presented by Panavision: The Ultra Panatar. Whereas the Super Panatar was a large and heavy sandcasted object, the Ultra Panatar had a thin diecasted shell, which resulted in a reduction of the weight. The Super Panatar was too heavy to be mounted on the projector's prime lens. Instead, it had to be mounted on the projector, meaning that a lot of dirt and dust could easily get caught between the prime lens and the attachment. Because of the weight reduction, the Ultra Panatar could be mounted onto the prime lens, becoming part of a completely sealed optical train. Another advantage of the Ultra Panatar was the elimination of image shift. When the expansion knob on top of the Super Panatar was turned, the image would expand but also shift from the center of the screen. This was normal, the Super Panatar would swivel its prisms in a linear way, which caused the image shift because the projectors were not on the center line of the screen. The Ultra Panatar had a built in correction device, which during expansion, left the image in the middle of the screen. Finally, the price was also an improvement: $495 a pair, compared to $695 a pair for the Super Panatar (13). By this point, Panavision had manufactured devices for two of the three fields of the cinema: A printing lens, and two projection attachments. There was only one field left, namely the actual photography of motion pictures. The article in "Film World", mentioned earlier in Chapter 2, stated that Panavision would manufacture anamorphic photography lenses. But it took some time before an official announcement could be made. In April 1955, MGM declared that a 65mm photography process would be employed for future important pictures and that special lenses had been developed by Panavision. MGM had done some experiments with 70mm dating back nearly 25 years. Those early [Mitchell] cameras could easily be obtained and modified. Douglas Shearer, head of the technical department at MGM, supervised the work and was assisted by Franklin Milton (14). Shearer had tested the Super Panatar and Micro Panatar extensively before purchasing them, which explains why Panavision would be brought into this project (15). The special Panavision camera lenses, to be known as the APO Panatar, had been under development for more than a year. The project emphasized the simplified operation of the lenses, since they would consist of an anamorphoser (expansion factor 1.25) and a prime lens. Normally, you would have to focus those elements separately. Ultimately, the main goal - to integrate them into one unit - was accomplished. Eddie Manx, studio general manager of MGM, "praised the focus sharpness and elimination of distortion" (16). The new system, not exclusively owned by MGM, was originally named MGM Camera 65, but later renamed Ultra-Panavision. Apart from the lenses, Panavision also modified the cameras, in co-operation with MGM (17). According to Richard Moore, "the cameras were as noisy as a cement mixer, so we had to blimp them" (18). An outer shell was placed over the camera, for the purpose of sound reduction. This shell, also known as a blimp, kept the sound inside the camera. A special feature of this system was the versatality of being able to make regular release prints in any aspect ratio required. In other words, the anamorphic camera negative would be adaptable to three strip Cinerama as well as 16mm flat (19). Of course, this meant chopping off the edges in the narrow ratios, like academy. On the other hand, the producer could now decide what release form to use after the picture was shot, instead of before. For this reason, Panavision provided MGM with a special Micro Panatar which converted the anamorphic 65mm image to any other decided ratio. The first film made in Camera 65 (Ultra Panavision) was "Raintree County" (1956, a year after the announcement by MGM), followed by "Ben Hur" (1959). Apparently, MGM considered only these films to be important enough to merit this system. Meanwhile, the legal contract was completed between the two companies, containing screen credit agreements plus an exchange of patent rights, and, a stipulation concerning further lens orders and optical developments (20). Perhaps this is the right place for a comparison of Camera 65 (Ultra Panavision) with Todd-AO, the 65mm system introduced a few years earlier by Mike Todd. The two systems are practically identical in almost every way. Both use 65mm film for photography and both have a release print of 70mm including the extra 5mm for the magnetic six-channel soundtracks. The difference is the aspect ratio. Due to the anamorphic attachment in front of the MGM Camera 65 (Ultra Panavision) lens, the projected image had a ratio of nearly 3:1, whereas Todd-AO used spherical lenses and had a projected ratio of 2.05:1. The different systems could therefore be shown on the same projector, except that the former needed an anamorphic attachment with an expansion factor of 1.25. To be completely accurate: The original expansion factor of the MGM Camera 65 system was 1.33. Why it was reduced to 1.25 is uncertain. George Kraemer recalls that the 1.33 expansion would eliminate two soundtracks. A modification like that would mean that Todd-AO would have a more diversified and sophisticated sound system, since Todd-AO and Camera 65 had been identical in sound system technology. MGM could not accept agree that lesser idea, because it wanted to have a superior (or equal) system in every way compared to the already-existing systems (21). Other sources state that the expansion factor was never changed from 1.33 to 1.25 (22). When the author saw a 70mm fragment of "Ben Hur" projected in the theater at Panavision, he checked the attachment which said "1.25 anamorphic power", a term identical to expansion factor. There are a lot of things concerning the Ultra Panavision issue which are unclear. The released 70mm prints seen today are rarely anamorphic, but mainly spherical and thus identical to Todd-AO. According to George Kraemer, there were only 100 theaters worldwide that could show the anamorphic 70mm prints because of the larger dimensions of the screen. The ratio of the 70mm spherical image does not differ that much from the anamorphic, so it is hardly noticeable that the original camera negative is wider. Of course, theater owners could modify their screen in such a way that the 70mm anamorphic print could be shown, meaning that the height of the screen had to be diminished. But why bother if a 70mm spherical picture was available? (23). The question then remains: Why did MGM develop it in the first place: Richard Moore stated that MGM just wanted a larger picture, not something identical to Todd-AO (24). MGM probably thought it could change all the theaters to 70mm anamorphic but theater owners had invested a lot of capital in obtaining the 70mm equipment and it seems likely that they were not eager to make another costly modification by installing a new screen and obtaining an extra anamorphic projection attachment at that time. But "Raintree County" was never released in 70mm, spherical or anamorphic, but only on 35mm anamorphic! This was due to the huge popularity of "Around the World in 80 Days", Mike Todd's second feature, which was being shown in every theater equipped with 70mm projectors. There was simply no capacity available for another 70mm release (25). In 1960, Shearer, Gottschalk, and Moore received an Academy Award for "the development of the system, producing and exhibiting wide film motion picture, known as Camera 65" (26). By that time [1960], Panavision had developed the first hand-held 65mm camera. It was the first camera Panavision had designed from scratch. Previously, production at Panavision had merely involved fitting lenses and attachments to preexisting devices (27). Another taking lens was made for 16mm in the beginning of 1955 (28). Richard Moore recalls it as not being a commercial success. "Our main business was 35mm; 16mm was marginal" (29). Another issue was another special Micro Panatar. "The Lieutenant Wore Skirts" (1955) was a CinemaScope film. Several shots, photographed for the purpose of background projection, were made with VistaVision equipment and 'squeezed' into the anamorphic negative by a Micro Panatar. The printer lens was ordered by Technicolor which supervised the laboratory work on the film (30). Perhaps now is the right place for a quick summary of Panavision's beginnings to this point. The company was two years old at the time of this Micro Panatar installation. So far, it had developed two projection attachments and sold more than 7,500 pairs to theaters throughout the world. Panavision had developed lenses for a new 65mm camera system for a large film company. Finally, it had developed three printer lenses and sold them to other companies. In particular, these Micro Panatars were important for the establishment of the company in the market of motion picture equipment. The first and second Micro-Panatar avoided double or even multiple shooting: One camera could be used during photography while the printer lens would take care of all other required ratios. This eliminated the extra cost during filming. Panavision became, therefore, very valuable to cost-minded film companies. The third Micro Panatar is important from a political point of view: The actual combination of two competitive systems, VistaVision and CinemaScope, in one film production seems like a milestone. One might safely say that Panavision was well under way to establishing itself.  In October 1957, the formation of Panavision Films, a sister company, was announced. Gottschalk stated that the 65mm system had been so successful, that the company should now plan to make its own films. The first production was to be based on the novel

"The Magnificent Matriarch" by Kathleen Dickenson Mellen. The content of the novel tells the - supposedly authentic - story of the conflict between the native inhabitants of Hawaii and the newly arrived white man. It was to be shot on location in Hawaii, in Camera 65 and Eastman

color. The film was budgeted at $2,000,000 and would have a running time of approximately three hours. Shooting would start in the spring of 1958. The released film, completed by the end of 1958, would first have a

'roadshow' version in 70mm. Panavision would handle the distribution itself, carefully selecting the theaters capable of showing it on a 3:1 screen, since the minimum width of the screen had to be 60 feet. After one year, the film would be released in a 35mm anamorphic version and distributed by a major studio. David Lewis, producer of

"Raintree County" was hired, as was a scriptwriter by the name of Frank Nugent, who had written "Mr. Roberts" among others. At the beginning of 1958, they both went to Hawaii to scout for locations and confer with the author of the novel (31). In October 1957, the formation of Panavision Films, a sister company, was announced. Gottschalk stated that the 65mm system had been so successful, that the company should now plan to make its own films. The first production was to be based on the novel

"The Magnificent Matriarch" by Kathleen Dickenson Mellen. The content of the novel tells the - supposedly authentic - story of the conflict between the native inhabitants of Hawaii and the newly arrived white man. It was to be shot on location in Hawaii, in Camera 65 and Eastman

color. The film was budgeted at $2,000,000 and would have a running time of approximately three hours. Shooting would start in the spring of 1958. The released film, completed by the end of 1958, would first have a

'roadshow' version in 70mm. Panavision would handle the distribution itself, carefully selecting the theaters capable of showing it on a 3:1 screen, since the minimum width of the screen had to be 60 feet. After one year, the film would be released in a 35mm anamorphic version and distributed by a major studio. David Lewis, producer of

"Raintree County" was hired, as was a scriptwriter by the name of Frank Nugent, who had written "Mr. Roberts" among others. At the beginning of 1958, they both went to Hawaii to scout for locations and confer with the author of the novel (31). Everything has to be perfect, and was going to be, except for one 'but': According to Richard Moore, it was all a dream. "Gottschalk and I were, deep down in our hearts, filmmakers. We entered the business of making attachments for the industry, because we saw the opportunity. What we really wanted was to make feature films. But there was no way we could realize a project like this, it was just too big and nobody would let us produce it" (32). So an alternative film was set up: "Dangerous Charter". Gottschalk presented it as an exercise, as a means of making a $100,000 picture look like a $500,000 production (33). The story was a melodrama: Three fishermen salvage an ocean-going yacht, find out that it belongs to drug dealers who force the fishermen to help them with their illegal operations. After the usual bloodshed, the good guys triumph. Shooting of the film was completed by the end of 1958 (34). However, the film was released in late 1962 by Crown-International. The critiques were not bad. It was considered as a good second half of a double-bill, due to its length, 75 minutes, and its strength, which was stated by "The Hollywood Reporter" as: "not strong enough for the top place. .... Gottschalk demonstrates a competent hand as a director, although the script is not very inventive" (35). Interesting though, was the fact that the movie was shot in 35mm spherical, which was somewhat embarrasing for a company that focused on widescreen processes. According to Takuo Miyagishima, who made the spherical lenses, it was just a matter of economics. "We could not tie up our lenses for this film" (36). The Auto Panatar Arrives What probably settled Panavision in the motion picture industry was the introduction of the Auto Panatar, a 35mm taking attachment. At this point, a comparison between the Auto Panatar and the already existing CinemaScope process is necessary. As was stated in Chapter I, CinemaScope had a lot of faults, shallow depth of field being one of them. However, the major short coming was the effect of the so-called 'anamorphic mumps'. When, say, an actor, moves toward the camera, or the camera moves to him, the camera lens has to focus during this movement in order to keep the image sharp. While the camera lens focuses during the movement from, say, a long shot of his entire body to a close-up of his face, his face becomes larger. This is normal, due to the magnification factor. During focussing a camera lens, there is a magnification change. But with a traditional anamorphic attachment in front of the prime lens, the anamorphic power reduces due to the magnification change. The closer the actor's face, the more the anamorphic power is reduced. This is only about 10%, but it is noticeable on the theater screen, where a constant anamorphic power is used to project the image. So in a close-up, an actor's face appears slightly fatter than normal. In the early CinemaScope films, the Director of Photography could find his way around this. The medium was new, the audience was getting used to it, so it was not that much of a problem that there were no close-up shots. But as more and more directors began using CinemaScope, it became an annoying limitation. In addition to that, actors were reluctant to be photographed in CinemaScope, because, while carefully watching their diet, they had fat faces during close-ups (37). This technical shortcoming was a severe limitation on CinemaScope, and Gottschalk knew that if he could eliminate this, he would have a major breakthrough. According to statements from some people at Panavision, it was Wallin who came up with the solution (38). On the other hand, according to Richard Moore, it was originally Gottschalk's idea. "When he bought two anamorphic attachments from C.P. Goerz for his underwater camera in the beginning of the 1950's, he discovered that by counter-rotating the first in front of the second the anamorphic power could be varied. It is my recollection that he would spend nights experimenting with lenses until he had found the solution. It might have been Wallin who designed the Auto Panatar, but it was Gottschalk's idea. He found out that, by inserting two counter rotating lens elements, the anamorphic power could be stabilized" (39). The Auto Panatar was demonstrated during a press conference at the end of July, 1958. Prior to that, it had been developed and supported by MGM, who provided the required facilities for tests (40). According to George Kraemer, MGM asked Panavision to manufacture anamorphic taking lenses because it no longer wanted to pay license fees to 20th Century-Fox for CinemaScope lenses (41). This might be true, but the writer did not find any newspaper announcements of actual collaboration between MGM and Panavision on this project. However, Gottschalk did mention the support from Eddie Manx and Douglas Shearer during the development of the Auto Panatar. An additional feature was the single focus, identical to the one the APO Panatar had. This allowed the anamorphic attachment and the prime lens to be focussed in one action. Another lens, the Ultra Speed Panatar, was demonstrated as well. It was also an anamorphic lens, but it could be used to shoot with a minimum of light. This allowed the director to shoot a film on location without the cumbersome generators needed to provide electrical power for the lighting equipment. Both lenses were hand-made and could be supplied to customers at the rate of two per month. The demonstration was very successful. MGM had already ordered 15 Auto Panatar lenses at $11,000 each, and Columbia also ordered a few (42). George Stevens, who was currently directing "The Diary of Anne Frank", wanted to use it on that film and bought one on his own account. However, as the film was a 20th Century-Fox production, he was refused the right to use the Panavision lens (43). Panavision later received an Academy Award for the Auto Panatar, in 1959. Other studios and independent producers, that could afford it, used Panavision anamorphic lenses from then on. Finally, in 1967, 20th Century-Fox dropped their own CinemaScope in favor of Panavision. According to George Kraemer, Fox was never able to eliminate the 'anamorphic mumps' in their system (44). Meanwhile, in October 1958, Panavision presented another widescreen process. It did not have a name at first but it was eventually named Super Panavision. This system was identical in every way to Todd-AO. Rowland V. Lee, was to produce "The Big Fisherman" and wanted to film it in a widescreen format. However, he was not satisfied with the existing systems, so he asked Gottschalk to develop a system that was adaptable to any theatre equipped with conventional widescreen. It appeared to constitute an improvement over Todd-AO since it was stated as being "capable of throwing a bigger, clearer picture than any widescreen process now in use" (45). Richard Moore, however, does not recall any significant difference between the two: "This is Hollywood. Put a name to it and sell it" (46). Around 1960, there were some changes in the management of the company. William Mann sold his optical company to Texas Instruments and then retired (47). Then Walter Wallin left. The reasons why are unclear. According to Richard Moore, "he was only interested in mathematics, did not care much about money, so there was no need for his stay" (48). According to George Kraemer, "He founded his own consulting company, mainly for military purposes" (49). That would indicate that he did need a major source of income. Another reason may also have been that there was not much for him to do at Panavision anymore. The Auto Panatar had been invented, so the years to follow might not have involved much more than refinements of existing technology. However, he remained friendly with Gottschalk who consulted him occasionally. Meredith Nicholson also left. He had served as a secretary treasurer at Panavision, but did not have any education in this field. He was a trained Director of Photography and chose to leave to become one again. Their shares were sold partly to the company, and partly to Gottschalk and Moore (50). A few years later, in 1962, Richard Moore left the company for reasons similar to those of Meredith Nicholson. He had a degree in Naval Plants, obtained from USC during WWII. He felt comfortable in designing mechanical parts, but he was more interested in shooting film. Nicholson had provided him with a union card, which enabled him to work at the big studios. "Without such a card you can only do marginal things" (51). However, unlike the others, Moore didn't sell his stock. In the 1960's, a new project was proposed. According to Takuo Miyagishima, the original idea was to go into a joint-venture with Mitchell Cameras, the largest camera manufacturer who had supplied all of the studios with their equipment. Panavision would design a 35mm silent reflex camera and Mitchell would build it. However, Mitchell was not interested (52). In 1962, MGM produced "Mutiny on the Bounty", a movie that went over budget (53). It caused that company severe economic losses, whereupon MGM decided to diversify its numerous departments. The costume, prop, and camera departments were sold to supply companies. Panavision was offered the cameras and related equipment. However, the company's financial resources were not sufficient for a complete acquisition, so future credit was given to MGM (54). Instead of going to Mitchell Cameras, the company now owned a large amount of cameras itself. However, the majority of the equipment was obsolete, and thus had to be modified to meet the standards of the day. The latest development in photography was the principle of "reflex". This device is a set of mirrors, located behind the lens and in the viewfinder. The photographed image is reflected via those mirrors into the viewfinder, which enables the camera operator to see precisely what is being filmed. Before the reflex-cameras, there was a separate viewfinder, located near the lens. The camera operator had to make compensations because he could not see precisely what was being filmed. Another issue was the noise level: The cameras were quite noisy. Some degree of noise reduction could be obtained by simply modifying the sprocket teeth. There are several different sound-causing movements during transportation of the filmstrip inside the camera. First, the film is taken out of the magazine by the sprocketteeth. Second, it leaves the sprocket teeth in order to be exposed. Third, the film is taken up again by the sprocket teeth. Fourth, the film leaves the sprocket teeth and goes back into the magazine, pulled by a belt-driven take-up motor. It makes a difference, concerning the soundlevel, whether the film is taken up, or leaving the sprocket teeth. So, in order to make the camera less noisy, the sprockets had to be modified for those different movements (55). But, again, the remedy involved a modification. The actual reduction of sound was mainly accomplished by an outer housing, a "blimp", which kept the sound inside. The result was called Panavision Silent Reflex, also known as the PSR. It is difficult to locate the exact date of the PSR's introduction. According to George Kraemer, it occurred around 1967-68 (56). Other sources mention "the early 1960's" and dates in between (57). This confusion of information supports the idea that the development of the PSR might have been a more evolutionary process, instead of a definite step forward, especially since neither "American Cinematographer" nor the "Journal of the SMPTE" mention anything about the PSR in the period between 1960 and 1969. Although there was a reduction in weight, the PSR was still heavy and bulky, according to today's standards. However, it was reported as being successful, one of the reasons being the introduction of the zoom lens. This type of lens gives its best performance when attached to a reflex-camera (57). During the same time period, the early 1960's, television used more and more film instead of videotape. Film cameras were needed to shoot TV series, and Panavision was approached for cameras and lenses. However, with the exception of the Super Panavision 70 lenses, the company only had anamorphic lenses. As a result, spherical lenses began to be manufactured for television and 1.85:1 motion picture photography (58). Finally, there was another event in the early 1960's which should be mentioned here. Panavision developed another printer lens in collaboration with Technicolor and Eastman Kodak. It featured a blow-up technique of a 35mm anamorphic image onto a 65mm filmstrip. Panavision designed it, Technicolor experimented with it in its laboratory facilities, and Eastman Kodak developed new color negative stock. It was first used on "The Cardinal" in 1964 (59). There are several reasons for the development of this device. * First, in the early 1960's, the number of theaters equipped with 70mm projectors was increasing. As a consequence, the potential audience for 70mm projection increased as well. * Second, especially outside the US, it was customary to raise the admission fee for a theater ticket if a film was projected in 70mm. American producers thus gained more revenue from foreign releases, if their films were projected in 70mm versions. * Third, the drive-in theaters had to wait until late in the evening before they could start with their show. As was pointed out in Chapter 1, a wider negative allows more light to reach the screen. As a result, the projected image increased in brightness. In other words, a 70mm print would allow the drive-in theaters to start their shows earlier, since it was no longer necessary to wait until it was totally dark. The number of shows per evening could therefore perhaps be increased, which was good from an economic point of view. * Fourth, the producer does not have to decide whether or not he is going to shoot the film in 65mm. He can use 35mm anamorphic, and after completion, decide if the film is going to be released in a 70mm print. * Finally, it is cheaper. The 70mm film gauge (for exhibition) became available for the medium-budget producer, who couldn't afford the more costly 65mm photography. There were some drawbacks of course, but they were not noticeable to the average viewer. Gottschalk stated that this blow-up process was not meant to replace Super Panavision and Ultra Panavision (60). Even though the printer lens was a breakthrough, it was also the death blow to most 65mm photography. As it was cheaper, the new lens eliminated entirely the more costly handling (acquisition, developing, and editing) of 65mm film. If a 35mm film was ready to be released, a blow-up could be made for the theatrical release. This particular technique was actually carried out. In the years to follow, the number of blow-ups would increase, whereas the number of 65mm productions would diminish. In 1969, David Lean used 65mm cameras for principal photography on "Ryan's Daughter", and it was not until 1991 that they were used again. In between, 65mm equipment was only used for special effects photography, or special sequences. For those who do care for 65mm photography in combination with 70mm projection, there is some good news coming up in Chapter 4. Summary Panavision could establish itself because it filled the right market niches. There are two prime examples: 1. The prismatic anamorphic projection attachments. This product was inexpensive to make and could, therefore, be marketed at a lower price compared to the existing cylindrical attachments. 2. The anamorphic camera lens. This item eliminated the so-called 'anamorphic mumps'. However, after introducing these innovations, how could Panavision retain its position as an established company? |

Further in 70mm reading:Introduction Super

Panavision 70

|

| The Innovation Phase 1 "Film Daily" 18 March 1955, pp. 10-12. 2 "Motion Picture Herald" 'Better Theater Section' 3 July 1954, p. 2. 3 "Film Daily" 30 March 1954, p. 1 ff. 4 "Film Daily" 24 December 1954, p. 7. 5 "Film Daily" 26 May 1954, p. 1 ff. 6 "Boxoffice" 3 April 1954, p. is unknown. The author received this paper clipping at Panavision headquarters with no page number on it. This issue is missing in the Library of Congress. Other tradepapers do report this meeting, but not this quotation. 7 "Wide Screen Movies" p. 67-68. 8 "Film Daily" 25 May 1954 p. 12. 9 ibidem. 10 "Film Daily" 27 August 1954, p. 11. 11 "Film Daily" 26 May 1954, p. 1 ff. It should be made clear at this point, that after "The Robe", Hollywood did not abandon the academy ratio. CinemaScope was only used for important films. 12 "Motion Picture Daily" 10 December 1954, p. 3. 13 "Hollywood Reporter" 18 March 1955, p. 3. "Film Daily" 18 March 1955, p. 10-12. "Showmen's Trade Review" 2 April 1955, p. 21 (E). 14 "Hollywood Reporter" 27 April 1955 p. 1 and 19. 15 "Daily Variety" 10 December 1954, p. 17. Moore, 11 July 1991. 16 "Hollywood Reporter" 27 April 1955, p. is unknown.(see note 6.) 17 "Film Daily" 27 April 1955, pp. 1 and 5. 18 Moore, 11 July 1991. 19 "Motion Picture Daily" 13 October 1955, p. 3. 20 "Film Daily" 19 October 1956, pp. 1 and 4. 21 Kraemer, 1991. 22 Herbert A. Lightman, "Why MGM chose Camera 65" in "American Cinematographer" (March, 1960), p. 162 ff. 23 Kraemer, 1991. 24 Moore, 11 July 1991. 25 "Why MGM chose camera 65". 26 Literal text perceived from Takuo Miyagishima, interview by author, 15 July 1991, Tarzana, California, video + audio recording. 27 Kraemer, 1991. Takuo Miyagishima, interview by author, 12 July 1991, Tarzana, California, video + audio recording. Moore, 11 July 1991. 28 "Boxoffice" 30 April 1955, p. is unknown (see note 6). 29 Moore, 10 August 1991. 30 "Motion Picture Herald" 19 November 1955, p. 25. 31 "Hollywood Reporter" 30 October 1957, p. 1. "Film Daily" 9 January 1958, p. 3. "Daily Variety" 6 March 1958, p. 4. "Daily Variety" 26 November 1958, p. 3. 32 Moore, 10 August 1991. 33 "Film Daily" 5 November 1958, p. 1 and 7. 34 "Daily Variety" 26 November 1958, p. 3. 35 "Hollywood Reporter", 29 September 1962, p. 3. 36 Miyagishima, 1991. 37 "Film Daily" 30 July 1958, p. 1 and 4. 38 Kraemer, 1991. Iain Neil, interview by author, 15 July 1991, Tarzana, California, video and audio recording. 39 Moore, 10 August 1991. 40 "Film Daily" 30 July 1958, p. 1 and 4. 41 Kraemer, 1991. 42 "Film Daily" 30 July 1958, p. 1 and 4. 43 "New York Times" 3 August 1958, (2) p. X5. 44 Kraemer, 1991. 45 "Boxoffice" 13 October 1958, p. 14. 46 Moore, 11 July 1991. 47 ibidem. 48 Moore, 10 August 1991. 49 Kraemer, 1991. 50 Moore, 10 August 1991. 51 Moore, 11 July 1991. 52 Miyagishima, 12 July 1991. 53 "Wall Street Journal" 25 June 1962, p. 24. 54 Kraemer, 1991. Miyagishima, 12 July 1991. 55 Miyagishima, 12 July 1991. 56 Kraemer, 11 July 1991. 57 "The Panavision Story". 58 ibidem. 59 Moore, 11 July 1991. Charles Loring, "Breakthrough in 35mm-to-70mm print-up process" in "American Cinematographer" (April, 1964) p. 224. George Kraemer and John Farrand stated that "Doctor Zhivago" was the first film which was printed up from 35mm to a 70mm release print but this article in AC confirms Mr. Moores' recollection. 60 "Breakthrough in 35mm-to-70mm print-up process". |

|

| Go: back

- top - back issues Updated 21-01-24 |

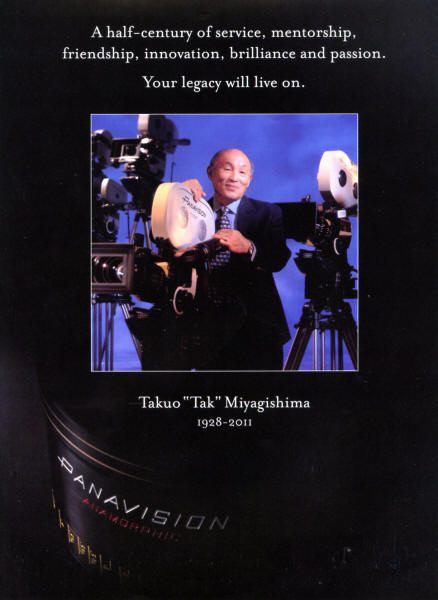

|