The Birth of an Idea |

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Ralph Walker, 1953 | Date: 26.10.2010 |

Ralph Walker, architect Ralph Walker, architectAn architect had a unique conception of a building for a client at the World's Fair of 1939 in New York. That concept had a profound influence on the evolution of what became known as the entertainment wonder, Cinerama. The story is told by the architect himself. Ralph Walker is well known in his field for many imposing structures, including telephone company buildings and oil research laboratories. He is a member of the firm of Voorhees, Walker, Foley & Smith. I THINK I SHOULD say at the very outset that this brief article is in no way intended to detract from Fred Waller's impressive originality of thought and surely the no less impressive persistence that has culminated in the successful presentation of his Cinerama. But inventions of this kind never spring fully-developed from one mind alone, pondering in splendid seclusion. They are the result of years of toil, of trial and error and trial again. Often the difference between success and failure is the discovery of a single clue, a key that unlocks the entire riddle. Waller and I had the good fortune to meet at a moment when I happened to be carrying just the key he needed. For some years Fred had been trying to impart to films a complete illusion of reality. From his background in special effects photography, combined with his innate genius for all things photographic, he had been approaching the problem from the direction of the wide-angle lens and multiple images on an extra-wide screen. Through actual experimentation he had arrived at the conclusion that much of our perception of depth is based in fact on what he calls "peripheral vision," those fleeting glances we catch out of the corners of our eyes. The obstacle, the stumbling block in the way of attaining peripheral vision on an ordinary wide screen was the fact that such a screen, to provide all the environmental details required to complete the illusion, would have to be the width of a city block. But all of his experiments had been upon the ordinary, flat screen, the screen that had been universally accepted as standard until the advent of Cinerama. As an architect, I had been concerned with a remarkably similar problem for a number of years before we met. In 1929 I was commissioned by Curtis Bok, the Philadelphia philanthropist and patron of music, to draw up plans for a new auditorium, an ideal theatre for the presentation of symphonies and opera. To me this was an exciting challenge. All too often such an assignment is hedged about with all sorts of restrictions— usually, getting the maximum number of chairs into the minimum amount of space. Here, on the contrary, I was asked to create an auditorium the only specifications for which were that it provide the finest acoustics and the best sight lines possible. |

More

in 70mm reading: The Entire Development of the Cinerama Process mr. cinerama The Birth of an Idea Cinerama Goes to War Adding the Sound to Cinerama This Cinerama Show Finding Customers for a Product in70mm.com's Cinerama page Internet link: |

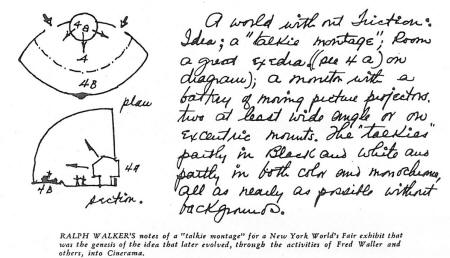

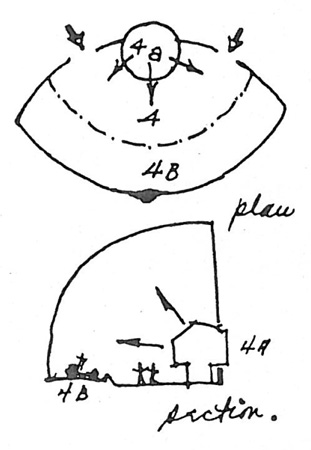

Click on image to see an enlargement Click on image to see an enlargementI began by making a study of existing theatres, both here and abroad. Repeatedly, I climbed up on the stage to see what the actors saw, as well as into the top balconies to get the audience's view—or, not infrequently, lack of view. I spoke to theatre people like Roxy, to musicians like Stokowski, and to numerous ordinary theatre-goers like myself. And gradually I came to think that almost all auditoriums have been constructed backwards. Most theatres are built like a megaphone, the mouthpiece at the stage, the widest part at the rear of the hall. Instead, I began to suspect, the plan should be just the reverse, with the widest part of the house being the stage itself and the seats banking up in gradually narrowing tiers. I reached this conclusion after, like Waller, I had studied the special characteristics and requirements of the human eye. I too had noticed the importance of peripheral vision in giving a sense of depth and perspective even to live action on a three-dimensional stage. I noticed how the downward sweep of the conventional proscenium cuts into the spectator's line of vision, reducing the illusion built by the settings of a play. I saw too that the conventional stage, with its slight tilt to provide a better view for the customers in the orchestra, was actually providing audiences all over the house with an excellent view of the stage floorboards while drastically reducing the effectiveness of the scenery itself. |

|

I had prepared nine very detailed sets of plans for my ideal theatre

before the depression came along and removed the need for any of them at

that particular time. In all of these, however, I stressed the removal

of what I like to call the "blindness of architecture," those details of

structure that obtrude between the spectator and his complete absorption

in the atmosphere of the theatre piece he is witnessing. I tried to

conceive an auditorium that would give the fullest play to just those

elements of peripheral vision that Fred Waller, quite independently, was

trying to achieve on the screen. I had prepared nine very detailed sets of plans for my ideal theatre

before the depression came along and removed the need for any of them at

that particular time. In all of these, however, I stressed the removal

of what I like to call the "blindness of architecture," those details of

structure that obtrude between the spectator and his complete absorption

in the atmosphere of the theatre piece he is witnessing. I tried to

conceive an auditorium that would give the fullest play to just those

elements of peripheral vision that Fred Waller, quite independently, was

trying to achieve on the screen.At this point we should have one of those old movie titles, "Five years later." In 1937 my firm, Voorhees, Gmelin and Walker was invited by the Petroleum Industry to prepare plans for an exhibit at the New York World's Fair. They wanted, they said, something that had never been done before. We worked out many sketches. I, with my special interest in the theatre, took particular pride in one proposed exhibit. I wanted a huge room, spherical in shape, on the walls of which would be thrown a constant stream of moving pictures from an entire battery of projectors. Through them, in a sort of contrapuntal montage, we would show the entire panorama of petroleum built around the theme of "A World Without Friction." I could manage the architectural end all right; what I needed to know was whether it could be worked out cinematically. And thus, enter Fred Waller. For expert technical advice I put in a call to an old friend, Charlie Bonn of the Jules Brulatour office. Bonn had only one name to suggest. It was, of course, Waller. "If it's within the realm of the possible," Charlie said, "Waller is the man who can do it for you." We met, and I think from the very moment I outlined my problem to Waller he realized that he had found the solution to his own. Not an entire sphere, but an arc - that was what he needed to delimit the field of vision and yet convey a sense of the all-embracing environment of his films. Furthermore, he realized, normal human vision is actually arc-shaped. The way our eyes are fixed in our head gives us a curved view of the world around us, a sweeping arc of about 160° wide and 60° high. If a picture covering .that same area were projected on a curved screen, he argued, anyone watching it would feel as if he were right in the center of it. Waller undertook the petroleum assignment in a fever of excitement, already looking forward to uses for this new form of motion pictures far beyond the scope of the World's Fair installation. Fired by his enthusiasm, Voorhees, Walker, Foley and Smith, our firm, put up some working capital and together we formed the Vitarama Corporation, an organization that still holds certain of the basic patents on the Cinerama machinery. Our ideas on peripheral vision coincided, and I felt that if anyone could put them into practical form, that man was Fred Waller. Eleven months later, Fred was ready with a working model which he demonstrated to some of the oil men in charge of the petroleum exhibit. They thought Vitarama was great—but perhaps just a little too radical for their purposes. As it turned out, they finally used a fairly conventional little puppet film for their show (although I do like to think that at least the auditorium in which it was projected, a huge triangular shed open to the sun on all sides, was somewhat unconventional.) Waller himself was called in to do the dramatic exhibit in the Eastman Kodak building, a vast mosaic of rapidly changing color photographs, and he was also a consultant on the motion picture installation within the towering dome of the Fair's perisphere. In the meantime, work went ahead on Vitarama. At this point it consisted of not only the now-familiar curving screen, but also a quarter-dome that capped it and seemed to swing the image far out over the audience's head. In the course of his experiments, Fred had actually gone so far as to chain together eleven cameras—and, to show his pictures, eleven projectors - in an effort to produce the effect of natural vision. Obviously, with all this complexity there were many technical obstacles to be overcome. And a good deal of extra financing needed to overcome them. We were able to interest Laurance Rockefeller in the project, and soon the whole Vitarama works moved into the old Rockefeller carriage stable on West 55th Street in New York City and Perry Coke Smith, one of my partners in the architectural firm, also became absorbed in the challenge of Cinerama. We stayed on with Waller through the development of the Waller Gunnery Trainer which proved so valuable during the last war, and contributed to its engineering and construction. Indeed, as time went by we all became so fascinated with the potentialities of Waller's new cameras that I realized one day a decision had to be made: Were we going to be architects or movie producers? I settled for architecture, although retaining a "sentimental" - and, with the current success of Cinerama - not unprofitable interest in Vitarama Corp. I know Cinerama is still imperfect. The difficulty of matching three separate images from three separate light sources still has to be worked out. But, as against any of the other wide-screen processes that have followed in the wake of Cinerama, I feel that Waller is theoretically on the right track to completing the illusion of depth perception in motion pictures without glasses. Cinerama most nearly fulfills the necessary requirements to fool the eye. And I have every confidence in Waller's ingenuity and inventiveness to bring his process to perfection. It is a confidence that was born sixteen years ago when we first sat down together to discuss the possibilities of creating something that had never been done before for a project that was never completed. |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues

- news index Updated 21-01-24 |

|