Sir Sydney Samuelson and Real Picture Quality | Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Interviewed by: Thomas Hauerslev. Transcribed for in70mm.com by Brian Guckian. Proofread by Sir Sydney Samuelson and Mark Lyndon for accuracy. Images by Thomas Hauerslev, unless otherwise noted | Date: 26.08.2013 |

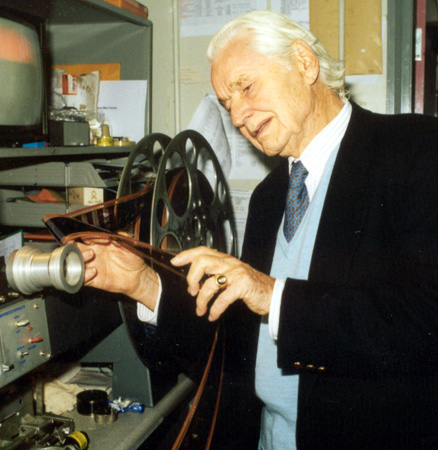

Ken Annakin | |

Ken

Annakin in Bradford, 2001 Ken

Annakin in Bradford, 2001TH: I think at this point we have been working our way around your career, so when I’m reading my notes I have some questions about...like Ken Annakin and "Battle of the Bulge" – but that was 65mm anamorphic, if you remember anything about that – Sir Sydney: Yes, well we serviced that one – that was shot in Spain. I knew Ken Annakin quite well – what film was it that he was most famous for? TH: "Swiss Family Robinson"..."Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines" – Sir Sydney: Go on, I’ve got the title, I know what it is – go back further...just testing you! TH: [Laughs] These are the films..."The Longest Day" especially – we showed three films for him in Bradford. I met him ten years ago, and he was so delighted to see his films on the big screen again. Very few Directors go back to see their own films on big screens – it’s so rare. So he was so happy to be with the audience, who came up to him and said, “That’s a good film, I saw that film in ´63” – Sir Sydney: What were the three films? TH: "The Longest Day" – the World War II film about the landing in Normandy – great film - Sir Sydney: The landing I don’t think was as well done as Spielberg did it in "Saving Private Ryan" – TH: That was more gritty, I think – I didn’t particularly like the beginning of that movie – Sir Sydney: It was pretty shocking – TH: ...that’s another story. And then we showed "Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines", filmed in Todd-AO, on the curved screen – Sir Sydney: ...filmed in Todd-AO – TH: – and of course, "Battle of the Bulge", in Ultra Panavision, and we showed that on the Cinerama curve, so he was very happy about that. Sir Sydney: Fantastic...now, earlier than that – TH: I can’t remember – Sir Sydney: I’ll give you a hint – documentary – TH: – I can’t remember – Sir Sydney: Documentary, colour, 3-strip, at sea...you may have never come across it, but it was given a general release...it was about 1945 – it was shot at the very end of the War, and it was called "Western Approaches" and it was shot with a Technicolor 3-strip camera – not the blimp – bobbing up and down in a little rowing boat. It was about the Merchant Navy and the havoc caused by the German U-Boats to the Allies’ Atlantic Convoys...and it’s a classic film for you to look at. I’m sure it’s available; whether it’s still available on – |

CHAPTERS • Home: A Conversation with Sir Sydney Samuelson • Cinema was always in my Family • Panavision, Bob Gottschalk and The Answering Machine • Stanley Kubrick, "Tom Jones" and one point • Dickie Dickenson, David Lean and British Quota Film • Stanley, Joe and "2001: A Space Odyssey" • Takuo Miyagishima, Robert Gottschalk and a 20:1 Zoom • David Lean and The Friese-Greene Award • Thunderball, Zhivago, Techniscope, and Fogging a roll of film • How lucky can you be More in 70mm reading: • The Importance of Panavision • A Message from Freddie A. Young • Stanley Kubrick • Shooting "Lawrence of Arabia" • Memories of Ryan's Daughter • Joe Dunton • Ken Annakin • 70mm in London 1958 - 2012 • The editor Receives BKSTS award Internet link: • George Berthold "Bertie" Samuelson (1889 - 1947) (PDF) • Samuelson Film Service (reunion) • samuelson.la • The Argus • British Film Industry Salute • Wikipedia YouTube/Vimeo • 'Strictly Sydney' • Clapper Board Part 1 • Clapper Board Part 2 • St. Mary's 1963 |

TH: DVD? TH: DVD?Sir Sydney: Well yes, it was shot on – of course 3-strip was 35mm – but it was to attempt to put a very large camera through, in this little boat, and it was cold, and wet, and windy. The cameraman was Jack Cardiff. TH: I met Jack – he went to Bradford as well, a number of times – great company. Sir Sydney: Yes – it’s a funny thing, when you see the Marilyn film, because he was a bit of a character, Jack; because Marilyn took a bit of a shine to him, as an older man – not romantically – he is not in the film...the new Marilyn Monroe film – TH: I remember one of the things I asked Ken Annakin about was how difficult it was to work with the 65mm cameras, and he said, “Well, if you’re used to working with 3-strip Technicolor cameras, 65mm cameras are so easy – you can lace it up in 10 minutes maximum”. Sir Sydney: Quite true – TH: Did you work on "Grand Prix" with Frankenheimer? Sir Sydney: Yes, and my son Peter, who’s the one in Los Angeles, he worked on – was "Grand Prix" the Steve McQueen one? No, that was "Le Mans" – but Peter worked on both of those films, and I think that "Grand Prix" was, equipment-wise, the biggest film we ever serviced. One item that we provided was a rushes theatre on wheels - it was actually a Land Rover pulling a 20-, 25-foot caravan which could be blacked out inside, with a screen, a 35mm double–head projector and a generator. And we had our camera car, which was built like a truck, with scaffolding points all the way around - and I know that we sent 3 vehicles, full of gear – the third one must have been one of our regular camera cars. But it’s not generally considered to have been a very good film. TH: But the Cinematography is fantastic – the way they put the cameras on the cars, and the way they shot it is amazing to see in 70mm. Sir Sydney: And do you know, and I know about this through Peter, that they had a special technician, and the only thing he did in his life, in his working life, was he made mounts to put cameras onto vehicles – he came from Hollywood somewhere. And so Peter got to know him very well; unfortunately he had a bit of a drugs problem, and it was the first time my son, who was on a break from University – a long vacation when he worked on that film – he was like the 9th assistant director – it was the first time he had to work with someone who had a big problem. TH: Another of my final questions would be, what it was like for you as the supplier of all the camera gear, to see the films once they were ready and premiered in the West End – what was that like? | |

Sir Sydney: Blimey, it was great! And a very big film we did, it was called

"Khartoum"...now I don’t think it was 65mm, was it? Sir Sydney: Blimey, it was great! And a very big film we did, it was called

"Khartoum"...now I don’t think it was 65mm, was it?TH: Yes, it was – Sir Sydney: It was? Let’s see, who was the Cameraman on that – I knew the Producer, very well, an American guy, and he was really good for us, because he loved our organisation. And he used to say, “There isn’t anywhere like this at home; there isn’t a firm where you can get everything that you want”. And he invited us, like almost honoured VIPs, to the Première of the film – it was Lawrence Olivier who played the Mahdi. And I’ll tell you another one; there was a film made about Mohammed – there were two films made about Mohammed, by an Arab producer – Moustapha Akkad his name was – and they were shot in Morocco. There was great political upheaval, because in Islamic culture the image of Mohammed is never allowed to be seen – and this producer of course, being Arab himself, he knew that, and he said, “You never see his image in my film; you only see the camera’s – from his point of view – and you just see a hand with a sword in it”. And it got to the extent – and I’d become really friendly with him (Moustapha) – he worked out of Twickenham Studios. When they were having the premiere of his film, "The Message" (1977), it was at The Plaza, Lower Regent Street – he received a telephone message and it said, “If you go ahead and show your film at The Plaza Regent Street this day, it will be bombed”. The producer phoned me, because we were going to the premiere, obviously; and he said, “Will you still come?” And I said, “Well, it’s got to be a hoax, hasn’t it” – and he said, “Well, I’m sure it is – but I have to tell you what has been said to me”. Anyway, I went – and there was nothing. [Chuckles] Just you asked me about going to the premières of films! Furthermore, there was about the time when I ran the 1982 marathon – when I was what – 57 I think. Why do I mention that? Because I was asking friends and clients to sponsor me – because I ran for the CTBF – the industry charity. And so I went to people to ask, “Would you like to sponsor me?” – I’m sure you do the same thing in Denmark, don’t you – and I went to my Arab friend, and amazingly – it may not sound like much today – this was 1982, so it’s 30 years ago – he sent a cheque made out to the CBTF to sponsor me for a Thousand Pounds! I was quite pleased if someone from a firm sponsored me for £50 – and he sponsored me for very much more than that. Where you went to the bathroom, in a frame is my shirt – you may have seen it, above the washboard. Anyway, there’s a badge for everyone who sponsored me, and my friend Moustapha’s name is up there. Also what’s up there is "Chariots of Fire" – because David Puttnam said, “Yes, I’ll sponsor you Sydney”, and when it came through, it was from the publicity account for "Chariots of Fire"...not that I had anything to do with "Chariots of Fire"; but it happened that "Chariots of Fire" was a film about athletics, and I was merely a 57-year-old jogger who went round the marathon course: whereas a proper runner does it in 2 hours and a bit, I did it in 4 hours and 37 minutes! But I finished, which is the important thing – certainly was for me, just a few thousand places behind the actual winner! | |

Happy Endings | |

Sir

Sydney Samuelson and Lady Doris Samuelson. Sir

Sydney Samuelson and Lady Doris Samuelson.TH: What kind of films do you like to see? Sir Sydney: I’m terribly basic and old-fashioned...first of all, I like satisfactory endings – I say satisfactory rather than happy endings, because “happy endings” sound so corny! But I’m absolutely no good at all at films with very complicated scripts – like films with flashbacks within flashbacks...I have to say to Doris, “Is she really living this, or is she dreaming this?”, and that kind of thing...I can’t get it. And there’s a film on that’s quite good – Oscar-nominated – and it’s called "Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy" – the script is so complicated that when Doris and I watched it we just couldn’t fathom what it was all about! Well, you must go and see "The Artist" – loved that film – and have you seen "War Horse"? TH: No – "War Horse" opened just last week I think in Copenhagen – Sir Sydney: Yes, it’s very good – TH: – and "Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy" opens in a week or two. Sir Sydney: Right; what I’m looking forward to is, after you’ve seen "J Edgar" – when you phoned me, I’ve ruined the film for you, because you’re going to spend all your time not watching the movie, but analysing the low-key photography...I think you’d have to call it “lowest-key photography”! | |

James Bond | |

|

TH: One other thing I wrote in my notes is

James Bond – the James Bond movies – Sir Sydney: There’s a whole lot of them! I’ve told you about the James Bond film which started everything as far as Panavision and Samuelson’s were fully concerned...Freddie I think did two James Bond films – TH: One – "You Only Live Twice" – that was number five – Sir Sydney: It was in Japan...we had an air-to-air cameraman; I think it was on that Bond film – his name was Johnny Jordan. He was filming from one to another helicopter – and they flew too close. Johnny Jordan had no fear, or nerves, or anything at all like that – and he was sitting actually with his legs outside the door, resting on a kind of skid that they put themselves down on, in a helicopter – and he got too near to the rotor of the one they were filming, and he lost the bottom part of his leg. TH: It was chopped off – Sir Sydney: Yes – and he was devastated – I think for the main reason that he was known to be the kind of brave, even daredevil cameraman who was very good, and happily did all these kind of jobs – and how would he now get work? I had a friend who was a newsreel cameraman with British Paramount News. He had been a war correspondent cameraman during the War and he’d trodden on a mine – and lost a foot. He wore an artificial bottom part of his leg – and when Johnny was home from Japan, and in hospital in the London Clinic, I went to see him. I knew he was absolutely down in the dumps – do you know that expression? – feeling very miserable, wondering about the future – so I took Bill McConville with me – who of course you wouldn’t know that he’d lost a foot. So I said to Johnny, in his time of terrible distress, “I want you to meet another cameraman, Bill McConville. And you’re in his club”. Johnny must have said, “What club are you talking about?”, and I said, “Well, to explain that, Bill would have to roll up his trouser”...which he then did. And I remember how kind of amused, touched, pleasantly reassured the poor fellow in the bed was, seeing that here was a chap who’s living a normal life, and even as a cameraman was still carrying on. And Johnny Jordan indeed did carry on; he had a prosthetic leg made and fitted. And do you know what happened to him in the end? He was on a film – that American film – what was it – David Watkin was the Cameraman – it was about how awful the American Army was...and the title of the film is an expression that gets used – "Catch–22" – do you know of that film? Who else was in it? TH: Alan Arkin I think – Sir Sydney: Johnny was doing air-to-air from one of those big American freighter planes, where the door at the end of the fuselage opens up, because they chuck great big packages and jeeps and things out of the back and they go down by parachute. You know the things I mean? Well you can fly with that back door open – and for that film, Johnny was set up with his mount, shooting out of the back of this C32 Lockheed Freighter...and, being Johnny Jordan, he didn’t need a safety harness or parachute, did he? And they hit some heavy turbulence, and Johnny went out of the back...and that was the end of him. TH: That’s terrible. | |

Helicopters | |

|

Sir Sydney: I don’t like helicopters – I don’t think they’re meant to fly!

But I have a lovely nephew, who’s a helicopter captain – he talks about it,

because he’s quite senior now – and he does a tremendous amount of flying,

for films, and for Sky and BBC News, and when there’s some kind of disaster

and they need to get shots from a helicopter – he does a lot of that work.

He’s talking about retiring – we’d all like him to retire! Once, in my business, we had our own helicopter – TH: At Samuelson Film Service? Sir Sydney: Yes, we had an Alouette II – French – bought it brand new, because a French pilot, Gilbert Chômat, came to see me; he said, “I’m coming out of the army" – he was a helicopter pilot with the French Army. Also, a guy called Lamorisse in France had built a mount – a helicopter camera mount that helped iron out the vibration [Ed. – Helivision system]. And then there’s another firm that we used to represent called Tyler – the Tyler mount – and Gilbert said, “I’m coming out of the service and I’ve heard all about your company – I’m the pilot who worked out a shot that you may have seen, in a film called "The Longest Day"”. It was an exciting shot – now I wonder if you remember it – it starts just a little above ground height...and it’s at the side of a canal, with a line of say, six American soldiers, with rifles – TH: Yes, of course, it’s the scene where they’re moving along a small harbour, and you have this helicopter shot – Ken Annakin talked about that...and it’s magnificent. Sir Sydney: Well, the young guy who came to see me was the pilot. He worked out what could be done. Because I think it finishes up where he’s quite high, and he goes over the top of a roof, and behind the roof are some German snipers. He said, “If you would buy a helicopter, it could be a completely new division of your services to the film and television industry, and I would like to come here and fly it for you. And I would like to come with my wife and four children”. And he did! And so we had the best helicopter service because of course it was Gilbert who confirmed we needed the Alouette II. There was also an Alouette III, but it was more expensive and bigger than we needed. That’s how we came to be in the helicopter business! We charged I think a hundred pounds an hour – it may have been £125 – again it’s a long time ago. And the going rate with other people who supplied helicopters, but hadn’t got a film pilot, like we’d had, who understood what the special requirements were when filming – we charged £125 an hour, and you would get Gilbert Chômat with the helicopter. And when you think what the production cost of a helicopter shot must be, £125 an hour is a tiny proportion. Nevertheless we would have people who would say, “Oh, I can get a helicopter and pilot for a hundred pounds an hour”. So we were not always overwhelmed with work. But Gilbert was so brilliant. I went to one or two sessions where he was planning the shots. He did all sorts of films, and commercials – commercials used him I think more than films – because they were only renting it for one day.  And what finally happened was there was a film – a Fox film called

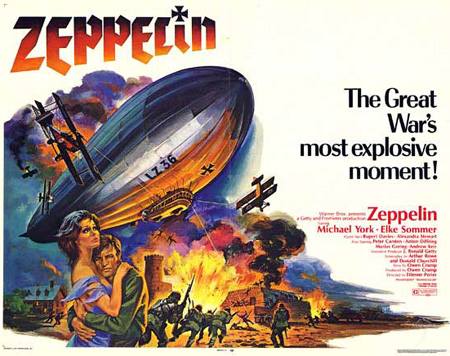

"Zeppelin"...and it was a First World War story. They were using, for

the air–to–air shots of the mock–up of a First World War Zeppelin, some

reproduction First World War fighter planes – German fighter planes, based

in Ireland. They were built originally for "The Blue Max" – ever

heard of that film? Good – I don’t think there are any films that you

haven’t heard of Tom, are there?! – And I think they were used also in

"Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines".... Anyway, the repro

German fighters are flown by Irish Army pilots – who are pretty good – they

fly in them in their spare time. And so when you want First World War

reproduction aircraft – I think they all have Volkswagen engines – you can

get four, five, six of them in Ireland...and the pilots, who know them, you

hire them at the same time. That side of it was nothing to do with us – we

were providing our helicopter, with our pilot. Before the Producer – production manager – an

American, quite well known producer, Burch Williams – his brother Elmo was

Head of Editing at Fox. The guy said, “Can you recommend a Cameraman to me?”

So I said, “Well we’ve several really good experienced aerial cameramen;

it’ll be a matter of who’s available”. I was able to phone him back and say,

“Yes, there’s a chap called Skeets Kelly” [Ed. – b. Graham Kelly]. Skeets

used to be Operator for Freddie Young, earlier than in the David Lean times

– immediately after the War. I think Skeets Kelly was himself a pilot during

the War – I think he had the DFC, then he became a very much in demand

second unit, action unit cameraman and did a whole lot of aerial stuff. And

when he was an operator, he was generally considered to be the very best

operator – if any other operator made a mess of something, someone else on

his crew would probably say, “That would never have happened if we had

Skeets” – he had that kind of reputation. And what finally happened was there was a film – a Fox film called

"Zeppelin"...and it was a First World War story. They were using, for

the air–to–air shots of the mock–up of a First World War Zeppelin, some

reproduction First World War fighter planes – German fighter planes, based

in Ireland. They were built originally for "The Blue Max" – ever

heard of that film? Good – I don’t think there are any films that you

haven’t heard of Tom, are there?! – And I think they were used also in

"Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines".... Anyway, the repro

German fighters are flown by Irish Army pilots – who are pretty good – they

fly in them in their spare time. And so when you want First World War

reproduction aircraft – I think they all have Volkswagen engines – you can

get four, five, six of them in Ireland...and the pilots, who know them, you

hire them at the same time. That side of it was nothing to do with us – we

were providing our helicopter, with our pilot. Before the Producer – production manager – an

American, quite well known producer, Burch Williams – his brother Elmo was

Head of Editing at Fox. The guy said, “Can you recommend a Cameraman to me?”

So I said, “Well we’ve several really good experienced aerial cameramen;

it’ll be a matter of who’s available”. I was able to phone him back and say,

“Yes, there’s a chap called Skeets Kelly” [Ed. – b. Graham Kelly]. Skeets

used to be Operator for Freddie Young, earlier than in the David Lean times

– immediately after the War. I think Skeets Kelly was himself a pilot during

the War – I think he had the DFC, then he became a very much in demand

second unit, action unit cameraman and did a whole lot of aerial stuff. And

when he was an operator, he was generally considered to be the very best

operator – if any other operator made a mess of something, someone else on

his crew would probably say, “That would never have happened if we had

Skeets” – he had that kind of reputation.Anyway, when I phoned Skeets he said, “Oh I’d love to do it”. I said, “There’s a producer chap called Burch Williams, and he’s looking for an air-to-air cameraman – it’s four days, with First World War aircraft, outside Dublin”. And he said, “I’d love to do it, Sydney; I love those old aircraft” and I said, “It’ll be Gilbert and our Alouette II”. He said, “Oh how marvellous”. He was delighted; he said, “I’d love to do it, but I can’t, because I’ve got a dental appointment”. So I said, “Well I’m really sorry to hear that Skeets, because I would want to recommend you to Burch and do your deal with him, and do the job”. And he said, “Let me see if I can postpone my dental appointment” – which he did. So I put him in touch. I’ve no idea what the deal was – nothing to do with me. We were just given where, outside Dublin, I think it’s called Bray, where the Irish film studio is. I think Waterford Glass is made in Bray. Anyway, he had to rendezvous at the airport where the German planes were, and that was all, as far as I was concerned. What he was shooting, and exactly when, and for how long, and all that was not anything to do with us, it was to do with the production company and the producer Burch Williams, and the cameraman, Skeets Kelly, what they were going to film. They had their briefing session, and I’d been to a number of briefing sessions with Gilbert Chômat and he was meticulous – he always used to finish, after he’d drawn on a blackboard what the shot was, where this aircraft would be, and what that aircraft did, and there was nothing left to the imagination, exactly what they were told to do. Finally, he made it very clear where he and the camera helicopter would be positioned. His last words, Chômat, he would always say, “Now just keep one thing in mind – we don’t know exactly where the wind is coming from, you never know how a shot is going to work out – it’s one thing for us to plan it on a blackboard, down here, but when we get up there, it may not work out. And we’ll go around and we’ll do it again”. He said, “The main thing is, if something doesn’t work out, you guys must carry on as we’ve agreed, and finish the shot as if we’re finishing it for real. I will then know what you’re going to do, because we’ve agreed what you’re going to do, and there it is on the blackboard. If there’s any trouble, leave me to get out of it. Just finish the shot, and fly where we’ve agreed you would individually fly to”. Something went wrong in the shoot – one of the pilots decided he would fly away – do a sharp left–hand turn or something like that. And he flew straight into our helicopter. Our pilot, the producer, Burch Williams, who was observing in our helicopter, and Skeets Kelly the cameraman – they were all killed. | |

Samuelson

Film Service's helicopter. Picture from Samuelson Film Service reunion site Samuelson

Film Service's helicopter. Picture from Samuelson Film Service reunion siteLater it turned out that although the film, "Zeppelin", had quite a sizeable budget, and Fox were not a cheapskate organisation, Burch Williams, their production bloke, had opted not to insure anybody. He didn’t have to insure our pilot or our equipment, because that was part of our fee – it included the pilot’s fee, the insurance for the pilot, and the insurance for the Alouette. But he hadn’t insured Skeets Kelly, who he had employed, so it was not my worry. But there was this marvellous, senior, experienced, great cameraman, at the end of his life: he was working, something went wrong, he wasn’t insured. I suppose Tom, if you said to me, “Tell me Sydney, what was the worst ever task you had to manage in all the years you were running the company?” I would have no difficulty in saying that the worst happening was when another friend (who was an aerial cameraman), Peter Allwork, phoned me from Bray, and said, “I’ve terrible news for you: one of the German fighters has flown into your helicopter and everybody’s been killed”. Because of course the Irish pilot was also killed. I said, “Have you phoned anybody else yet?” And he said, “No, I thought I should phone you first, no doubt you’ll want to tell the widows, will you?” I said, “Yes, well I’ll have to”. So the worst job was to get into a car and go and tell two women that their husbands had just been killed. And when I arrived at Gilbert’s home, which was very close to our firm, there she was, his widow, with her four small children around her, two of them holding onto her skirt – two little tots, all only French-speaking at the time. The children must have wondered, “Who’s this man?” And that was the most tragic thing, I think, business-wise, I ever had to cope with. Really terrible. But you know, even that awful story, Tom, there’s a nice aspect to it because – again I don’t mind you knowing – I approached my “Number Two” at the firm, my brother Michael. I said, after I told him what had happened – and he was of course terribly shocked – I said, “I have to tell both their wives, how would you feel about doing one of them?” And Michael said, poor fellow, “I don’t think I could...I just don’t think I could”. And so I had to say, “OK, alright, I understand. I’ll go to Anne (that was Chômat’s wife) first. And then I’ll go and find Skeets’ wife (I’d never met her)”. And the nice bit about it is, we had a young woman who ran the admin of our helicopter department, in other words, when a booking came in, she would take down all the details, she would discuss the rental price, she’d take down if they wanted to rent the camera equipment from us, if they wanted to rent a Tyler mount from us, the dates for everything – where and when Gilbert had to be, were any passengers going to be flying with him, to the location, who was the cameraman or did they want a cameraman recommended – all the admin, Sharon Gold looked after. And at that terrible moment, when I sort of must have had my head well down, as I prepared to leave with one of our drivers to go on this terrible mission, to the two wives, Sharon said to me, “Would you like me to come with you, Mr. Sydney?” Now there’s no fun attached to doing that, she didn’t have to do it, but she asked, “Would you like me to come with you?” – and she did. I didn’t take her up to the front door of the two houses, but at least I had somebody to talk to. Probably I discussed what I was going to have to say to them – but I always thought, you know, what a marvellous young person, that she would volunteer to go on an awful task like that. So I had good people with me – that’s why the firm was so good. | |

|

TH: A terrible story. Sir Sydney: It is a terrible story, I’m afraid. Although not directly involved, there are two other filming helicopters that I knew about, which crashed. And in both cases everybody was killed. One was Lamorisse, who invented the helicopter camera mount and was a cameraman himself. He had a favourite pilot in Paris, with an Alouette II, and they used to do the equivalent, for films and commercials, and so on. And they had been involved in an accident, and Lamorisse the cameraman and his pilot were both killed. And when our pilot came into my office and I said to him, “You’ve heard about Lamorisse”, and he said, “Yes, I’ve heard about him, a terrible thing, because we were partners in France for so long, and we worked out how to do filming from a helicopter without vibration”. And then Gilbert said to me, “I’ll be next”. Don’t know why he said that, but he said it. Anyway, he was the next great film aviator to die. Terrible. And the third one was – you know the film "Guns of Navarone"? Do you remember that film? TH: J Lee Thompson – Sir Sydney: Yes – CinemaScope. Then there was a sequel – TH: "Force 10 from Navarone" – Sir Sydney: Fantastic. They had a helicopter on it, and when they’d finished shooting one day – in a manner of speaking, this was the most desperate tragedy of the three accidents – when they’d finished shooting, they were going back – the camera crew and the pilot, in the helicopter, to their base – they were in Yugoslavia filming a great viaduct across an open space and the story of the film was that the partisans – the Tito troops – had to blow up that viaduct to stop the German occupying army being able to use it. Well, they used a model for the blowing up, but the actual viaduct they also did shooting of action on it, with German Army trucks going across it, because it was the real thing. And I suppose there were a number of miles between the real viaduct and the base. And so when they’d finished filming of the actual viaduct, aerial shots, and they’d not enough light left anymore – they had to fly back to their base. Don’t know how many miles it was, but probably an airfield somewhere in Yugoslavia. And the pilot thought he’d do a bit of showing off – you know what I mean about showing off – and he flew under some power cables, and he wasn’t quite low enough – and that was the end of them. Isn’t that shocking? TH: It’s a terrible story. And why would he do that? Sir Sydney: Why would the captain of an Italian cruise liner sail so close to an island where he had friends on shore who he wanted to impress? They’re trying not to say it, but right at the beginning somebody was interviewed who said, “Well look, that ship often comes by, and they all wave to us”. These are the people who live on the island. And I think he was probably just showing off, both to his friends who lived on the island, and to his passengers on his great big ship. TH: It’s so bizarre – so unreal to see a ship this size just – phwit – Sir Sydney: Who would do it! I’d like to think, if I’d started and studied, in the Merchant Navy, and had become whatever it is, a Fourth Officer – Fifth Officer, whatever – and I’d become a Fourth Officer and then I’d got a job on a Liner, and I’d become a Fourth Officer on a Liner, and a Third Officer, and a Second Officer, and then there is another senior rank – a four-ringer – not the Captain, but there is someone else – there’s the Chief Engineering Officer – he’s got four rings – and there’s another officer who’s like Number Two to the Captain – and I think he’s got Captain rank – and then, I would have become a Captain, wouldn’t I? I would have thought I was so proud, to be trusted as the Captain of a ship with three thousand people, my responsibility – I would like to think I wouldn’t be taking any chances to wave to my friends. How could he? He is not a youngster, not like a 21-year-old Battle of Britain pilot, flying low over his airfield. TH: He seems to think like he’s more or less a rock star – irresponsible, completely irresponsible...that’s a different story. But I know what you mean. Sir Sydney: Do you know of a film called – was it "Reach for the Sky" – about the RAF during the War – and it was a story of an RAF fighter pilot called Douglas Bader, who lost both his legs before the War, in a flying accident. But he managed to fly, during the War, with two artificial legs, and he became a brilliant fighter ace, flew Spitfires, and he was one of the most decorated pilots because of the number of aircraft he shot down. I suppose Messerschmitts and Heinkels and things – he was a Group Captain (equivalent to a full colonel) and his story – going right back to when he was a young pilot in about 1935 – and how he’d been showing off, which young pilots are forbidden to do. It’s like they kind of reach their home base and they see their mates sitting in deckchairs around, reading the papers and so on, and they decide to “beat them up”. So he comes in over the edge of the runway and flies very, very low over them, at three or four hundred miles an hour – they can be dismissed for doing it, but nevertheless some of these young kids used to like to do that. And if the day before a young RAF pilot had shot down two Focke-Wulfs and then “beat up” his friends on the airfield, I don’t suppose they’d court martial him and take him away – we were so short of pilots anyway! And what happened to Bader was he had this long career during the War, and artificial legs, and then, he was shot down and was taken prisoner and put in Colditz Castle, because even so, he tried to escape! I was telling you about that iconic fighter pilot because I had something in mind. Me, wearing a different hat, do you know what BKSTS is? You must do – are you a Member?  Thomas

Hauerslev and Sir Sydney Samuelson, Odeon Leicester Sq, London, 14

December 2009. Image by Paul Rayton Thomas

Hauerslev and Sir Sydney Samuelson, Odeon Leicester Sq, London, 14

December 2009. Image by Paul RaytonTH: I’m an Honorary Member, you gave me the Award! Sir Sydney: Of course I did! What am I thinking...it’s my age you know! [Laughs] I want to put another expert film pilot’s name forward for an Honorary Fellowship – he’s not a Member of the BKSTS, but we have an Honorary Fellowship for people who are not actual film or television “techies”, but still make a contribution to the industry. And I want to put Captain William Samuelson’s name forward to the Council, so that he might be considered (it won’t be up to me) for an Honorary Award. I need his CV. And you may have heard about Ridley Scott; as it happens, the house we had before this one, about 30 odd years ago, was up the road in Hampstead. And when we decided, as two of our children were away, married, we didn’t need a house as big as that. There was just our youngest son and Doris and me, and so we decided we would sell that house. It had ten bedrooms! [Laughs] But it was a lovely old circa 1700 listed Queen Anne period home – a lovely house. Ridley Scott bought it – Will just told me he is now shooting the third of his big, medieval or whatever, action films. This one is called "Prometheus" – don’t know what "Prometheus" is, or who he was. They were on the Isle of Skye, in Scotland, and Ridley arrived to meet the Cameraman and the helicopter crew. Ridley wanted to meet his Cameraman – I suppose it was somebody local there, and so the cameraman introduced himself to Ridley and said, “This is our Pilot, Will Samuelson”. He may have said, “Captain Will Samuelson”, because in the aviation world, that’s what he is, a fully–qualified helicopter captain. Anyway, apparently Ridley was just talking about some matter to his Production Manager, and when he heard the name "Samuelson" he stopped – he said, “Any relation?” [Laughter] And Will said, “Yes, I think so, Mr. Scott”. He said, “So what relation are you, to that family I know so well?” And Will said, “They’re my Uncles”. And so Ridley apparently said, “Oh, Sydney or Michael?” Well, Sydney’s still here, but Michael died a few years ago. And so Will said, “Tony” (my brother Tony, who you wouldn’t know, because he was the one of the four brothers who wasn’t a technician – he was a lawyer, and he looked after the financial side of the business). And Ridley was so nice, and so pleased to find someone connected to old-timers, us, in our industry. But those bloody helicopters – they’re a pain – and so dangerous. TH: I can understand that now, after talking about your various experiences with them. Sir Sydney: Especially the last one. And that’s why we’ve compared it to the irresponsibility of the captain of the Italian cruise liner. | |

|

• Go to next chapter:

How lucky can

you be • Go to previous chapter: Thunderball, Zhivago, Techniscope, and Fogging a roll of film • Go to full text: Sir Sydney Samuelson and Real Picture Quality • Go to home page: A Conversation with Sir Sydney Samuelson | |

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |