Director of Photography Ben Brahem Ziryab |

Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Interviewed and photographed by: Thomas Hauerslev, January 2019 in Copenhagen, Denmark. Transcribed from audio recordings by: Mette Petersen. Lightly edited for continuity and clarity. | Date: 10.05.2019 |

Danish

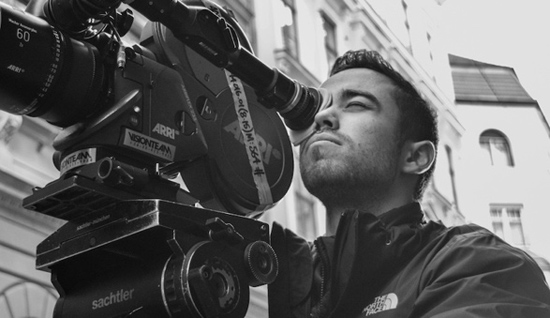

Cinematographer Ziryab Ben Brahem behind the 65mm 8-perf camera on the set

of "Daughter of Dismay" Danish

Cinematographer Ziryab Ben Brahem behind the 65mm 8-perf camera on the set

of "Daughter of Dismay"Thomas Hauerslev: You were born in Copenhagen in Denmark [in 1992]. Please tell me about what inspired you to become a cinematographer? Ben Brahem Ziryab: I grew up in Copenhagen. My parents came here as immigrants back in the '70's. None of my parents worked with films or did anything with film. My mom still works for the UN and comes from a UN medical background and my dad works as an electrical engineer and he did have an interest in photography. My dad is from Tunis and when he grew up there he dreamed of having a Swedish Hasselblad camera. It's medium format, it's 6 by 6 and it has this beautiful depth of field and amazing quality. At the time, it was the RollsRoyce of cameras, which I think it still is, in terms of film-based medium format. My dad really wanted that. That was like his dream - getting a Hasselblad camera, and he knew it would never happen for him as kid.

It never happened. He went into engineering and never pursued photography. 35 years later, I was born in Copenhagen and as a kid I was interested in the normal stuff that kids do, like being a firemen, a policemen and playing soccer. All these traditional things that were part of being a kid growing up. And all of a sudden, my dad thought

It would be great to give him something

different, other than all the traditional toys and things. So he bought me a

medium format film camera as a very young kid. I was maybe 7 years old,

something like that, and I had no idea of how to use it. I had no idea of

how load the the film, how to expose. All this was completely unfamiliar to

me, but I got the camera and started playing with it. I was actually hooked

from the beginning. Not so much about photography. I didn't really care too

much about that. I was really interested in the mechanics. How the camera

works, how to make this very complex and really nice camera work. We

travelled a lot when I was young and eventually learned how to load the

camera. I would take just travel pictures, which was amazing on this medium

format camera. At the time I didn't know how amazing it was, but now I

really know how powerful it can be. Not every shot was in focus. Not every

shot was exposed well. At the time I was using slide film [reversal, or

diapositive, ed]. The exposure

latitude was really narrow, so you had to really nail the exposure, otherwise

you would get the image too bright or too dark very fast. It was very

unforgiving as a medium. |

More in 70mm reading: 65mm Horror Short "Daughter of Dismay" "Daughter of Dismay" with Director James Quinn VistaVision Strikes Back From YouTube To 65mm Film in70mm.com Interview & People |

Ben Brahem Ziryab

with a Panavision camera. Picture supplied by Ben Brahem Ziryab Ben Brahem Ziryab

with a Panavision camera. Picture supplied by Ben Brahem Ziryab THa: When did you decide to become a cameraman? Ben: I think it was when I realized that I didn't want to become a director. I thought the next best thing would be be a cameraman and that also made sense to me, because I loved cameras. THa: How did you start in the motion picture business? Was it a conscious decision or did it happen by accident? Ben: Once I knew I wanted to work with film it was completely conscious. Everything I did from that point was going towards "How do I get into the business?" So, from going to these internships in Denmark I went straight to the US. I wanted to get out of Denmark, because I wanted to go somewhere else. I just wanted a different environment. In Denmark, in the winter time, it gets really cold, so you always want to go somewhere warm. I thought the US made sense and I thought "Well, if I have to go to the US, somewhere warm, it has to be either LA or San Diego". San Diego [in 2011] just happened to be the school that I liked the most at the time, so I went to San Diego State for film school. It is a film school, but it is also an undergraduate program that is part of a university. There is a film school as part of the university studies. So, it was film studies, like theory studies with practical production training. THa: Was San Diego State where you learned how to become a cinematographer? Ben: I think it was a gradual process. I didn't learn lighting at school. That was one thing I didn't know how to do properly. That came after school, when I realized lighting was really important. But at school I didn't know that, and I was really focusing on learning the equipment and learning the protocols on set and how to work as a team. How to piece together a production. The mechanics of a film production. And that is what I learned from school. And I also had some real good experience with making films and getting critique from mentors and craftspeople. That was really helpful, because that sometimes harsh criticism really made me give ideas a second thought. I sort of learned a lot from that. I think I progressed in film school, through the critique and through the work experience I had. And another benefit from going to film school is meeting people. And those people, are still to this day people I am working with and hopefully continue to work with in the future. In film school, this was during the very transition between film and digital. This was when digital was taking over for good. Theaters were changing to digital and film schools started to think ...,

That was when they thought it [film] was

going, and it was going to go away. So they started to pull away the film

stuff. Luckily I learned how to load a 16mm camera in school, which is cool,

but they went digital, so we just started learning that. Luckily we did have

a Panavision film camera at school. The school had an agreement with Panavision: If you

were really good and you got a project and you wanted to make it, you could

pitch it to their committee, and they would give you a Panavision camera for

free. And then you could go out and shoot for one week or two weeks and come

back. FotoKem was also really generous. They gave us good discount on the

processing. So if you really wanted it, you still had that opportunity to go

and shoot film and learn with film. That was what I did. I thought I want to learn digital. I want to be familiar with

it and I want to go

to the classes and learn digital stuff, but I still think film is more interesting. I

really

want to stick to that. |

|

A

VistaVision frame from "The Negative". A

VistaVision frame from "The Negative".Actually "The Negative" came out from San Diego State. That was my thesis film and that was after having done 35mm. So I did 16mm and 35mm productions through film school, because we had free camera and discounts. And for the thesis film I thought well, "I've got to do something different.". I remember at the time that I was really interested in John Ford films, the westerns, in particular "The Searchers" was a big hit for me because I really liked that film and how it was shot and how it was composed. I was always fascinated about the way they put the horizon line in the frame. I also noticed something interesting when I watched Hitchcock films and these John Ford film like the "The Searchers" or even other films I watched at the time: I often saw this logo in the beginning: "VistaVision Motion Picture High Fidelity". "What is VistaVision"? It was interesting, so, I went on the Internet to find out what VistaVision was. "Ok, it is 35mm films, it is not vertical, it is horizontal. The camera is on its stomach, and it is high resolution, because you are exposing 8 holes instead of 4 holes. It is more image". So, I thought that will be kind of interesting to shoot in VistaVision. I also did some research on it and realized that people hadn’t really shot VistaVision for many years. It was used for special effects, because it is 35mm and high resolution. It is still being used for special effects for films like "Interstellar" and "The Dark Knight", but it has not been been used as a narrative format for many years. And moreover, it has never been printed and projected [only in rare cases, ed] in that format. That was really the thing and I had never seen a VistaVision film before, and didn't know how it would look like, or how to even get the cameras. "Did they even exist anymore?". That was the question. I knew they had to exist somewhere, because the special effect people still used them. I did my research and I found this company in LA that had the VistaVision cameras. Unfortunately, they were a little reluctant to rent them out to students. That was the only one in LA and they wanted to make sure that the camera was safe, which I understood. I thought that this was the end, because I had already done some other research and got a lot of "No"s. Then finally this guy found a camera, Albert I think his name was, and he sent me an email saying something like,

I gave him a call, and it was a voice message. He might call me back or he might not, we will see. And he called me back and he said:

He sent me all the camera parts.

Everything. He was really generous, and he didn't even know me. That was

amazing, and it happened really fast. I spent two days with him over the

phone to learn how this hand-built camera works. The manual is not exactly

like the camera. It was a lot of guesswork but luckily, he was available via the phone

for us and was really generous in guiding myself and my first AC [Assistant

Cameraman] through. We got to learn how it works and after two days we just

drove out to the middle of nowhere essentially, which was Monument Valley as

you see in "The Negative". |

|

A

Century VistaVision projector head. A

Century VistaVision projector head.Because it was either that, or at Paramount Studios ['s VistaVision projector] in Los Angeles. There was no way we could get all the people to Paramount from San Diego State. That was not going to happen and we wanted our movie to be the final show at the screening event. When then the image came on the screen and there was just ... silence. I think people were quite impressed. "The Negative" was a really successful project and I actually ended up getting an ASC nomination for cinematography. Which was awesome! So that was my thesis film. I later worked on commercials and short films and music videos and anything I could work on. I think that I worked in LA for a year and then I got offered my first feature. That was great and then I did a second feature and worked on some other stuff, documentary stuff for UN organizations actually. Basically, it was just one thing that led to another. So, the first feature led to the second feature, second feature led to the third feature and meantime I have all these commercial jobs and documentary jobs in between. And this is two and a half years ago. I came back to Denmark, because my visa had expired, and the rule is that you have to go back and apply from your home country. Then this Danish film maker contacts me and says:

I said "sure", and it actually

started as a Super 16 project, but I thought that 35mm was a more

appropriate format. That was Simon [Wasiolek] and we went out and did this

short film "Diamant Pigen" on 35mm film. It was all photochemical

post[production], there is no digital intermediate. All old school and

surprisingly, I don't think it has been done in Denmark for a while. I don't

know how long, but film has, as a capture format, been phased out [in

Denmark]. I believe that we were one of the first to shoot film again and

specifically with photochemical printing. Then we couldn't find a loader,

because all of the people who used to load film, were now first AC's and

they didn't want to go down and load film again. Literally we looked

everywhere and finally found this person who had no experience loading film. We

taught her, and did a little workshop with her. She was great and she did

really well. That was "Diamant Pigen", which is coming out this year

on film. |

|

|

THa: What are the challenges to photographing a film with a VistaVision

camera? Is it more complicated than a regular vertical camera or does it

require any special attention? Ben: I can only speak for the Beaumont VistaVision camera which is the one I used. I would say it is very straightforward, loading-wise. You can learn it very quickly and the Beaumont VistaVision camera uses the same magazines as the ARRI 435 and 235 cameras. They don't require any special modification. They can run any standard ARRI 435 magazine. The difference being the loop size has to be bigger. So, it is very conventional, mechanically speaking. Now you are recording an image that is twice resolution of what you are used to, with a depth of field that is, depending of what lens you have used, tends to be very shallow. So you do have a challenge of how to keep things in focus, one, and two, it brings the whole art direction to a different level. Everything has to be art directed to a higher standard, because you are seeing everything. You are seeing small pieces of grass in the background. You are seeing pores in skin. You are seeing extraordinary details in the image. And that makes everything, makeup and art direction-wise more difficult, and the focus is critical. But other than that, I think, as far as the way you set up the shot, it is pretty much the same as a standard 35mm camera. There is not much difference. THa: How do you focus? Is it a reflex camera? Ben: It is a reflex. We use the Leica lenses, which are actually lenses for a still camera. They are much more challenging to pull focus with, and there are a whole set of problems when putting a motor on still lenses. Actually I believe Panavision has a special set of lenses for the VistaVision camera that are rehoused. It is Leica glass, but they are rehoused so you have a longer focus rotation. It is easier to make the small focus adjustments. So that is something that would help a lot, but we didn't have it. THa: I noticed in "The Negative", that it was a challenge to photograph the bugs, and keep them in focus. Ben: Oh yes, that was hard, but as long as you have a predictable plane to focus on and you know where it will be you can do it. Having the rehoused lenses would have helped. THa: It was very impressive even on a small computer screen. One shot, which I like, is the shot when the camera is completely rock steady and you have this mountain range in the background which is in focus. You see them walk to the right, a bit out of focus, so you can see the depth of the image. It is staggering. Ben: That is also one of my favorite shots because there is so much detail in that one image. That is pretty amazing. I think it was shot with a longer lens, so actually you have that shallow depth of field and the compression in the image and all those beautiful things. THa: Would you recommend to go out and shoot in VistaVision? Ben: I think so. I would not recommend for someone who has not shot film before. But for somebody who has shot 35mm, the transition is easy. The step is not very big. I would recommend getting a good AC. Also one must keep in mind that for VistaVision, there are only a very few sound sync cameras around. |

|

|

James said "Let's do that". We did

look at 15perf, which is the Imax format, 15-perf, 65mm film. For budget

reasons we thought that that was just a little bit too expensive. We found

this other format which has actually not been used very much. It is 8perf,

65mm, but instead of the film going horizontally [like IMAX] it actually

goes vertically, like 5perf and we thought "Well, this is kind of an

interesting medium", and 8perf 65's projection aspect ratio is actually

very similar to the 1,43:1 Imax. So, you could release it in both formats

without breaking the bank, essentially. We looked into it and we talked to

Andrew [Oran, FotoKem] and he said there are only few theatres left in the

world that

still do 8perf projection, so it is not growing,

unfortunately. |

|

Cinematographer Ben Brahem Ziryab

in Nyhavn, Copenhagen, 10. May 2019. Picture by Thomas Hauerslev Cinematographer Ben Brahem Ziryab

in Nyhavn, Copenhagen, 10. May 2019. Picture by Thomas HauerslevTHa: What will be the running time of it? Ben: It is only 5 minutes. 5 or 7 minutes. 7 minutes with the credits. It is a short, short film, and very arthouse. THa: How is photography in 65mm different from a modern digital camera in your opinion? Ben: I think 65mm is a very different story than VistaVision and 35mm. All the issues are taken to yet another level: Vibration, emulsion buildup, severity of jams etc. The amount of force required to pull that large a film through the movement and stop it is pretty amazing, especially at high speed. Then you have focus. The depth of field is very shallow and the mechanics of the lenses are not great, so it’s a very tough job and you have to a experienced focus puller. If you are shooting in a dark space especially, I will recommend that you have rehoused lenses and a very experienced focus puller. THa: Can you use the same lenses on a digital camera? Can you take a Hasselblad lens from the Magellan 65 and attach it to a RED camera? Ben: That is one thing that we actually tested in preproduction. "How do we test lenses?" Because we don't know if the distance marks are accurate. We test that, we wanted to put them on a digital camera like an ARRI Alexa 65 and look at it, and see if the distance marker is accurate. Especially with the Hasselblad lenses, there is a very short focus rotation, so you don't have those individual space in between it, and plus, if the distance scale is not accurate, you are going to have soft focus. I recommend, either put them on digital camera and test them out, or have them rehoused, so that you know that the scales are 100% accurate. That is a big thing FOCUS. The lenses themselves optically are beautiful and they perform great. THa: What is the primary concern when shooting 65mm, compared to digital? It is the focus issue, you have to be careful about, because of the large format? Ben: There are many issues, not only focus. It is much harder to shoot 65mm unless you have a DP and a crew that really knows the format. I would also warn that the cost of shooting in 65mm is extreme compared to large format digital. THa: Either on film or large chip Ben: On film you have to be a little bit more careful, because you can't see the focus through the viewfinder, no matter how good it is, it is just … THa: ... only on the Magellan Ben: On the Magellan you might be able to. That is true. That is a big advantage although some AC’s say you always need an optical viewfinder for critical focus. THa: That is one of the selling points, you can actually see something in the Magellan viewfinder. Ben: That is critical in large format ... getting precise focus, and the magnification too, I mean you are magnifying the image. You are actually magnifying it less, but when the screens are so big, any mistake is going to be evident. Especially in IMAX. You are seeing more than the human eye, so things that you even wouldn't be able to tell with your eyes, are now going to be in the focus and sharp. It is going to be there and anything from shooting in the desert you may leave tracks, so you have to clean the sand. You can't have it to look that there has been a film crew walking across the desert. All these different things ... continuity in your art direction has to be held to a higher standard. And makeup as well, because of the clarity of skin tone. THa: Did you experience that your colleagues were aware of the fact that they had to be more careful on VistaVision and in 65? Ben: Well, we had a discussion before, so they were aware of it. Everybody knows that this has to be perfect. It is like … when everything is perfect, it is 10 times better, but when everything is not perfect, it is also 10 times worse, you know. THa: When can we watch "Daughter of Dismay" and how should we watch it? Ben: It is a European production, and hopefully it will be out in the beginning of April [2019] for the festival and I think in 70mm 5perf or 15perf both ways would be good ways to see it. As long as it is in 70mm. It should be 2,20:1 on 5perf and about 5 minutes plus titles and credits. If cinemas want to show "Daughter of Dismay" they can contact the director James Quinn. |

|

Danish

cinematographer Ben Brahem Ziryab. Picture supplied by Ben Brahem Ziryab Danish

cinematographer Ben Brahem Ziryab. Picture supplied by Ben Brahem ZiryabTHa: Who inspires you and why? Ben: I think there are a lot of people, certainly people like Terrence Malick. I am a big fan of Terrence Malick. I thinks he makes wonderful films. Christopher Nolan, I think he is really great with what he does. His movies, and that he can do the things he does. Basically, they are very artistic movies and on a commercial budget. I think it is fantastic that he is able to combine those two things. Paul Thomas Anderson is another one that I really like. David Lean is also a good one. Those are the main ones. THa: What inspires you about David Lean? I am really inspired by him. I watched "Lawrence of Arabia" in 70mm here at Imperial Bio for the first time. I think that I was very young, I don't know the exact year [2008]. I didn't really know what 70mm was at the time, but I realized that it was something really magical about the picture and the experience of it. I was seeing that something was beyond what you would normally see in a theatre. It was a magical experience, and that was how I would describe it. And I think the 70mm has a lot to do with that. I watched "Baraka", which was at the same festival, and I really loved that, and which was also a kind of at testament to the power of the format. The way it creates intimate portraits, everything from intimate portraits to big beautiful landscapes. I would say that the main inspiration would be David Lean's "Lawrence of Arabia". To me, that is one of the best films ever made. It really inspired me for the whole time I have been making films. I always go back and think of "Lawrence of Arabia". It is like the Gold Standard, and as high as you can go. I don't know if I will ever be able to make something even close to that, probably not, but that is kind of a dream, to aspire to that. It is kind of the prize. THa: But when you read about 70mm, people always refer 70mm and the vistas, but I think that 70mm is really, really good at portraits ... Ben: Absolutely THa: Is 65mm more suitable for one kind of scene or another kind of scene? Ben: In 70mm I think that we all have to make a distinction between 2,20:1 and IMAX, because I think that these two have different experiences. In general, say 5 perf, I would say that most films would work in 70, because it is not just for big vistas, not just for travelogues, it is not just for showing locations. I think it is just as powerful as a portrait format, and the fact that you are so close with the characters, in terms of the clarity, in terms of the 3dimensional aspect to the image, makes the characters much more intimate to the audience. That is another thing about 70 that I love, the power of the close up in 70mm. It is a bit of a misconception: 70mm has always been looked at as the format that is for big vistas and for travelling the world, and all these things. I think that it is really not. I think that any subject matter, any film, any type of film, whether they are small or big, could work. On any format, however, depending on your intention, maybe that you have very intimate emotions that you want to put on a very big canvas or maybe not. But if your intention is to take very intimate emotions and really amplify that, I think that 70mm is the perfect format for such a move. So, to describe 70mm in three words it would be: Intimate, beautiful and 3D, actually. Because for me it is 3dimensional. It is 3D without glasses. Even "Lawrence of Arabia" ... if you look at the closeups of Peter O'Toole and Omar Sharif, and all the closeups, they are soo … because essentially the film is actually not about the vistas as much as T. E. Lawrence's character, and the fact that he is trying to find himself. He doesn't know who he is, and the discovery of his character is what it's all about. I think that the format really helps us get to know him. |

|

|

So that would have been the death of film,

and the labs face the same problem. We were this close to losing film, and

now we have multiple labs processing film. I have a positive feeling. I am

optimistic.

People became interested in

VistaVision and reached out to me after that film - film for one, and

secondly every time I go to show the film, I get tons of interesting questions. It is

wonderful. It really inspires people, especially my generation. They didn't

grow up with film, per se, I mean, we might have seen film, when we were

really young, but we didn't really grow up with shooting on film. I

think that my generation and new generations as well, will experience the

film experience much differently than maybe your generation. They see it as something more interesting and certainly

different than digital. Because it is not what they are used to. It is

different. |

|

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |

Cinematographer Ben Brahem Ziryab

in Nyhavn, Copenhagen, 10. May 2019 inspecting a clip of 70mm film. Picture by Thomas Hauerslev

Cinematographer Ben Brahem Ziryab

in Nyhavn, Copenhagen, 10. May 2019 inspecting a clip of 70mm film. Picture by Thomas Hauerslev