The Birth of IMAX |

Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Diane Disse, The Big Frame, Spring 1994. Diane Disse, former editor of The Big Frame, teaches writing and is the student media advisor at Western Oregon State College near Salem. Reprinted with written permission from Kelly Germain, Giant Screen Cinema Association | Date: 31.08.2011 |

The Imax technology was born at Expo '70, where viewers rolled through the

theater on a rotating platform. The Imax technology was born at Expo '70, where viewers rolled through the

theater on a rotating platform.What the Japanese delegation saw when it arrived in 1968 might have been an illusion—or a foreshadowing of the future. In New York they visited a floor of offices filled with people engaged in filmmaking. In Montreal they visited another office, well furnished and looking very businesslike. When they got the royal treatment on a tour of a Montreal office complex with experimental filmmaking and the business of filmmaking impressively united, they were sold. Their hosts did not waste time explaining that the New York office was just two rooms rented by Graeme Ferguson as a base for his independent filmmaking. Nor did they note that the furnished office in Montreal had been, just days before, a production room holding office furniture, and even prints for the walls, that had been rented by Roman Kroitor. They also failed to mention that the final tour was, in fact, of the National Film Board of Canada's (NFB) facilities, where Kroitor had worked for years. When members of the Japanese delegation left, they were satisfied that the funds and prestige of Fuji Bank and its associated businesses were in good hands. They were right, but there were fewer hands than the bankers thought. The enterprising hands they were placing themselves in were those of Ferguson and Kroitor plus Robert Kerr, and, later, Bill Shaw. The promise these 30-something men made was to produce a film for Expo '70 in Osaka, Japan—and, along the way, to develop a new camera to shoot images on a film frame 10 times larger than a 35mm format, new equipment to project those larger frame images onto a six-story-high screen, and other little things—new lenses, sound equipment, lighting, and seating arrangements. In addition to being risk takers, they shared most other characteristics of successful entrepreneurs. They had skills and knowledge specific to their task. They were willing to postpone financial success. They were persistent. They could approach a problem from various angles. They shared interests and skills but also had well developed specializations. |

More in 70mm reading: in70mm.com's IMAX Page The Passing of Bill Shaw Bill Shaw about Jan Jacobsen The Work of Jan Jacobsen Jan Jacobsen Story Widescreen Gathering |

Just Enough Experience | |

"Tiger Child" was the first Imax format film, created for Expo '70 in Osaka.

The idea for the format struck Graeme Ferguson at the Expo '67 in Montreal

as he watched a complicated system using multiple projectors. "Tiger Child" was the first Imax format film, created for Expo '70 in Osaka.

The idea for the format struck Graeme Ferguson at the Expo '67 in Montreal

as he watched a complicated system using multiple projectors."We had just enough experience to give us some confidence. We were very naive - which probably saved us." Ferguson, Shaw, and Kerr went to school together in Gait, Ontario. Ferguson and Kerr's first venture together was starting a school newspaper when they attended Gait Collegiate Institute. Ferguson began making films when he was a student at the University of Toronto and was selected one summer to intern at the NFB. He became an independent filmmaker, eventually working out of New York. In 1965 Ferguson was asked by the Canadian Expo Corporation to do a film for Expo '67 in Montreal, but it had to be done by a Canadian company. Kerr was serving as mayor of Gait and still managing the printing company he had sold. Ferguson approached him about setting up a company to co-produce. Kerr agreed. "At that age you think the world's your oyster," he says. "We had just enough experience to give us some confidence, and if it didn't go, we still could recover. We were very naive - which probably saved us." For Kerr the venture was going to be part-time, looking after the business end. They produced the film Polar Life for Expo '67 in Montreal. Kroitor too had been a summer intern at NFB and went to work full-time there when he finished university. In 1965, he suggested the Board form a committee to produce a multiple-image, experimental film for the Montreal Expo. Kroitor's concept was selected, and he produced "Labyrinthe". |

|

Collaboration Grows | |

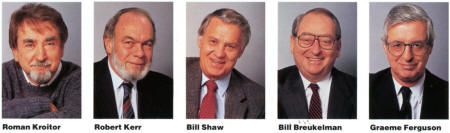

Roman Kroitor,

Robert Kerr,

Bill Shaw,

Bill Breukelman,

Graeme Ferguson Roman Kroitor,

Robert Kerr,

Bill Shaw,

Bill Breukelman,

Graeme FergusonClick the image to see enlargement The Montreal Expo turned out to be a showcase for big-screen films shown with multiple projectors. Other forerunners in big-screen production were there, including Colin Low, Kroitor's codirector on "Labyrinth", Christopher Chapman, Francis Thomson, Alexander Hammid. Ferguson remembers calling on these people for advice as Imax developed. The audience reaction was great, according to Kroitor, but the process was technically complicated and the images never seamless. He remembers Ferguson saying they "ought to be looking for a way to make these films without multiple projectors." Their chance to do that came when the Fuji group asked Kroitor to do a film for Expo '70 in Osaka. Kroitor proposed a new company to do it and invited Ferguson and Kerr to join him. They sold the Fuji group on the idea and then had to deliver not only a film but also a whole new system. Multiscreen Corporation, now Imax Corporation, was in business, with Ferguson as president. But they needed technical assistance. The camera turned out to be an easy project for inventor Jan Jacobson, a Norwegian working in Copenhagen. In 2½ months he designed a new camera to use 65mm film horizontally. The projector was a tougher problem. The company had acquired a patent for a Rolling Loop projector from Ronald Jones, a machine shop owner in Brisbane, Australia, but it needed adapting for the larger size. Their old friend Bill Shaw came to mind. |

|

Something Adventurous | |

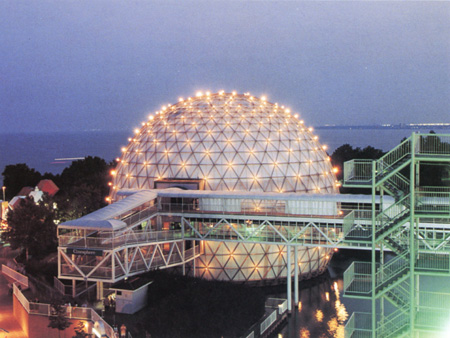

The first Imax projector, showcased at Expo '70, is still in use at Ontario

Place's Cinesphere in Toronto, Canada. It was installed in 1971. The first Imax projector, showcased at Expo '70, is still in use at Ontario

Place's Cinesphere in Toronto, Canada. It was installed in 1971.After university, Shaw, who said there "was never any doubt I would be an engineer, but I needed to make an effort to become more business oriented," had joined Ford Motor Company partly because of its management training program. After a few years there, Shaw went looking for a smaller company where he could be involved in more depth. He picked CCM, maker of sporting goods and bicycles, and was product engineering manager there for nine years. "One day Graeme and Robert showed up at my desk and said they had this marvelous idea," says Shaw. But they needed someone who understood chain drives—like those on bicycles. Shaw, then 39, said, "I figured if I didn't do something adventurous then, I never would." Shaw worked with Jones, usually via air mail, to develop prototypes for the larger-format projector. Even though the concept of building up a loop before each frame was projected seemed like the ideal way to ease the big film through without tearing the perfs, the prototypes continued to shred film when they ran at the necessary 24 frames per second. Meanwhile, Kroitor was producing the film so it could be shown with either single or multiple projectors. From the summer of 1969 to the spring of 1970 when the Osaka Expo opened, Kroitor worked in Japan. His wife Janet (Graeme Ferguson's sister) and five children, ages 3 to 13, were with him. Working with him was the late Donald Brittain, one of Canada's foremost directors, and Georges Dufaux, cameraman, who had been on NFB and returned to head the technical services division of the Board. Asuka Productions, co-producer of the film, provided facilities, assistance, and a new piece of equipment to edit the film. |

|

Fighting Discouragement | |

The convention that "married new technology and art"

was conceived at Expo '67. Today, in its third decade,

Imax enters a new era under new leadership. The convention that "married new technology and art"

was conceived at Expo '67. Today, in its third decade,

Imax enters a new era under new leadership.Raising funds was a constant problem. Ferguson and Kerr had acquired some capital and loans, and they had advance money from Fuji, but it wouldn't cover the cost of developing the projector. While Kroitor was in Japan, he got a call from Kerr and Ferguson saying they couldn't continue work on the projector unless they could get $100,000. Kroitor went to Fuji and got an advance using the projector, not yet working, as collateral. Kerr reports each of them was discouraged at times, but "I guess what saved us was we weren't all discouraged at the same time." Shaw admits to being discouraged "maybe once a week" at first, but then he'd go to sleep and wake up ready to try a new idea. A year before Expo '70 was to open they still weren't sure the projector would work, but Shaw was able to show mathematically that a new prototype would work. In three months the new machine was built, and at 1:30 on a Sunday morning in June it ran for the first time. Ten minutes later, it had successfully passed its tests, and a few months later it was being installed in Japan. The projector was installed in the Fuji pavilion, and the film "Tiger Child" was shown on the big screen while the audience was carried through the theater continuously on a large rotating platform, each one viewing the endless film from a different starting point. During the six months of Expo '70, the system was inoperative on only one day. Shaw notes the important role Expo's have played in developing new technology. "The sponsor usually has a good budget," he says, and those developing the technology and art "can take risks because you only have to keep it running for six months." |

|

Around the World | |

|

As remarkable as the accomplishment for Expo '70 was, it was not the goal of

the small company. That goal, as Ferguson expressed it, was to have one

projector for the large screen and a "standardized system that could be used

by everybody around the world." They wanted to take the big screen out of

Expo's and into everyday experience and make it commercially successful. The development of Ontario Place in Toronto offered the first opportunity to do that. The government-sponsored theme park was to include Cinesphere, a theater showcasing new technology. Ontario Place bought the Expo '70 projector. It was brought back from Japan, refined a bit, and installed in the spring of 1971. That first Imax projector, not rebuilt until three years ago, still runs at Ontario Place. The company also provided the first film for Ontario Place, "North of Superior". The next milestone in the development of the company was the opportunity to use the system with a dome screen, in a new kind of planetarium in San Diego—the inauguration of Omnimax. About this time William A. Breukelman, now chairman of Imax Corporation, came on board to aid in the fundraising and business effort. The Imax founders continue to work on "the marriage of new technology and art," Kerr's way of looking at what they have done. Sharper images, larger images, and improved concepts all are part of the drive to "fill the audience's field of view," says Ferguson. Those working in the industry continue to strive to blur the line between observer and participant in the theater experience. |

|

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |