Douglas Trumbull - A Conversation | Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Prepared for in70mm.com by: Brian Guckian (Ireland) | Date: 15.11.2012 |

|

|

More in 70mm reading: Douglas Trumbull - See the conversation High impact immersive widescreen filmmaking with Douglas Trumbull Doug Trumbull Gets an OSCAR Blade Runner: The Original 70mm Engagements 25th Anniversary of "Brainstorm"'s 1983 Release "Brainstorm" in 65mm “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” 70mm openings The Original Reserved Seat Engagements Of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ Journey To The Stars World's Fair Cinerama facility in Seattle Internet link: Laserhotline Talstr. 11 D-70825 K o r n t a l Germany Fon: +49 (0) 711 832188 Fax: +49 (0) 711 8380518 |

|

| • Douglas Trumbull • Jacques Vallée • Overview Institute • Noetics Institute • Nicolette Sheridan • Ricky Jay Gerrit Graham ("New Magic" as Jeremy) Sir Christopher Lee ("New Magic" Mr. Kellar) Showscan Entertainment (New company) Trumbull Lecture opticalpodcast.com episode 010 opticalpodcast.com episode 11/ |

|

| |

|

| |

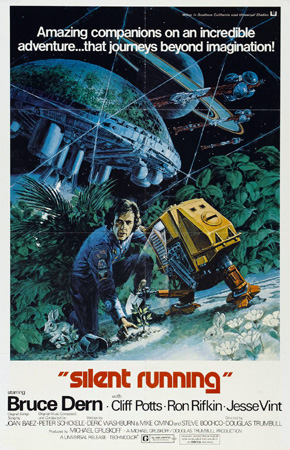

DT: – Yes. DT: – Yes.WH: So after your success with "2001", the next thing that came along I think was "The Andromeda Strain", for Robert Wise – were the visual effects in 65mm? DT: No – that was all 35mm. At that time I didn’t have any 65mm equipment; it was a very low budget movie, from a special effects point of view. Most of the work I did for "The Andromeda Strain" was effects that were going to be rear-projected onto screens, in the laboratories. So that was 35mm rear projection. WH: And then, “Close Encounters of the Third Kind”? DT: No – "Silent Running". WH: OK, that’s a film you made – you made two films as Director, which were released in the cinema – "Close Encounters" was just for the visual effects. OK, let’s talk about "Silent Running". Your first job as a Director – how did the project come about? DT: Well, it came about through some relationships I had with friends at the Studios, and agents; and there was a very interesting moment that happened at Universal where this movie called "Easy Rider" came out. "Easy Rider" surprised everybody – it was a very profitable, low-budget independent film that no-one understood. The Studios just didn’t have any idea how to do this. So they decided to experiment with five or more films – one-million-dollar independent films. I can’t remember all the other films, but there was a Kurt Vonnegut film you probably remember, then there was "The Last Picture Show", there was "Silent Running"...I can’t remember the others. But anyway, the whole objective was that the Studio would experiment with making five or more one-million-dollar movies, and not have anything to do with them – they would put up the money but they wouldn’t see the script, they wouldn’t have Final Cut, they wouldn’t do anything. So I had this amazing experience on "Silent Running" where I got complete control, as long as I stayed within budget. So it was a really great experience; it was a very simple movie, it was a very low budget movie, it was made with a very small crew, and shot in 32 days. Shot on board this aircraft carrier, airplane hangar, with a lot of miniatures – I kind of learned how to direct during the making of that movie. WH: So was it due to budgetary reasons that it was only 1:1.85? DT: Yes – that was not enough money to make a big spectacle, in 70mm. |

2015:

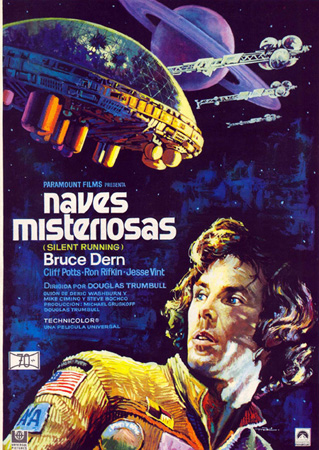

Douglas Trumbull's "Silent

Running" screens in Bradford |

70mm

poster from Mexico 70mm

poster from MexicoWH: And also I understand some 70mm prints of the film have been made? DT: No – not that I know of...I’ve never heard of that. But there was just recently a restoration done, in England – I can’t remember the name of the company right now, but there’s a really beautiful Blu-Ray restoration – it’s quite nice. It’s the best version of the film I’ve ever seen – better than the original prints. WH: The music in the film was composed by Peter Schickele and the songs by Joan Baez – how did that come about? DT: Well, you have to remember this was the early seventies: Flower Children, Vietnam War and all kinds of issues going on, and I was a big fan of Joan Baez’s music – I had many of her albums; I was part of that scene. And I noticed that I was really liking the orchestrations and the music behind her singing, and I would look on the albums and there was Peter Schickele, and well, I wanted to find someone who wasn’t in the movie business, to do something different. So I contacted Peter, and he said he was willing to do it, and he came and did the score for the film and did a beautiful job, an unusual job, and then he ultimately helped me with Joan Baez, because I wanted her to do the song, which Peter wrote with another woman named Diane Lampert. And it was kind of an interesting story, because she was very, very busy at the time – she was extremely popular, travelling all over the world, performing everywhere, and Peter was calling and calling and calling, and he couldn’t get a return call. And just by complete freak chance I was in Chicago Airport changing planes, and I saw Joan Baez get off another plane about 100 yards away. And I just went over and talked to her; I said, “I’m Doug Trumbull, I’ve been trying to reach you to work with Peter Schickele, would you do the movie?” She said, “Oh yeah, OK”. So we got her [Laughs]. WH: So did she do it for a small budget then? DT: Sure, everybody did. WH: I think it became a sort of cult movie – I think in Germany it was released only on television...I think it never made it into theatres. DT: That’s possible – WH: Did it earn its money back in the US? Theatrically? DT: Yes, but it was another business experiment that Universal tried, on "Silent Running", which was to see if they could get word of mouth to carry the film rather than an advertising campaign. So they did no advertising for "Silent Running", which hurt the movie very badly. So it took a long time to make its money back – it did, but it was very disappointing for me to have the movie not be promoted properly by the Studio – it was another little social experiment they did. WH: And I read on that film names like John Dykstra, and also Richard Yuricich worked on that film as well – did they start some years before? DT: It started John Dykstra’s career, and many others that worked with John Dykstra, like Wayne Smith – John and Wayne and a whole lot of the crew came from Long Beach State College, from the Industrial Design Department. I found them, and we hired them to build all the sets, and do all the conversion of the aircraft carrier and help build the models and everything. It was quite a clever mixture of a few Hollywood professionals, like Charles Wheeler, who was a Cinematographer and Camera Operator and Gaffer; Harry Sundby who was a really good Lighting man, and [we also had] a wonderful Editor. But a lot of the crew that actually did the work to fabricate the movie were students. And that was a great experience, and I’ve always believed that that’s a really good way to go. | |

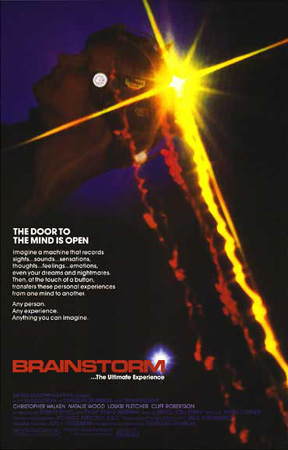

WH: The next directorial project you did was

"Brainstorm", which was much

later – in the meantime you concentrated on doing visual effects. Did you

get many offers to direct? WH: The next directorial project you did was

"Brainstorm", which was much

later – in the meantime you concentrated on doing visual effects. Did you

get many offers to direct?DT: I had many, many offers as a Director; "Silent Running" made me very popular in Hollywood for directing jobs. And I went into a process of developing projects – so I had science fiction movies in development at MGM, Columbia, Warner Bros. and Fox. And in that process of developing these projects, all of which were sitting on my shelf, unproduced, I just had all these tragic experiences happen, that I had no control over. For instance, we had a really amazing sci-fi adventure called "Pyramid", written by David C Goodman; it was a really terrific script and it was going to be produced at MGM. And then Kirk Kerkorian, who owned MGM, just closed the Studio and decided to build a Casino in Las Vegas. So the project just ended. That was a year of my time. Then I had another production with Arthur Jacobs, who’d done "Planet of the Apes" – a kind of big underwater adventure movie, it was kind of like "The Abyss" – and Arthur Jacobs died, suddenly, of a heart attack. And the whole project got tied up with his estate. And then I had a project called "The Ride" – I was very interested in theme park rides, as almost a narcotic form of entertainment. It was at Warner Bros., and then suddenly all the management changed and the project got dropped. Now I can’t make a living – I want to direct these movies, but they’re not happening. And that was when I talked Paramount Pictures into forming this company called Future General Corporation, which was a research and development company to look at the future of cinema technology. And that’s where we invented the Showscan film process, the simulation rides, interactive video games, Magicam – Magicam was this compositing thing: real-time video special effects. And so that went very well for year, getting that started. And then all the management at Paramount changed – get me out of here! So that was when "Close Encounters" came along. And Paramount agreed to loan me to Columbia Pictures. I wanted to meet Steven Spielberg; he had just come off "Jaws", and I thought he was a really interesting Director, and I thought, “Well this’ll be cool”. And it was a way to get 65mm cameras – because I said to Steven, “I’ll do this job if we can do all the special effects in 65mm” – because I wanted the cameras for Showscan. So I had my own agenda going on. But it was a really great opportunity to work on that movie – we developed the first motion control system, recorded camera movements on location, Richard Yuricich developed all kinds of amazing optical printing techniques to get those beautiful, soft, glowy UFOs and motherships and everything – it was a tremendous amount of fun. WH: So what was it like, working with the young Spielberg? DT: It was great – Steven was adventurous enough, and powerful enough, to get the Studio to do things that they didn’t understand. And in those times the visual effects budget for "Close Encounters" was high according to what they thought it should be, and they had no idea. Steven managed to get the money for us, and convinced the Studio and the Producers that we should do all this, and it was at a time when Columbia Pictures was in a tremendous amount of financial trouble, and if "Close Encounters" had not been very successful I think the Studio might have gone out of business. It was a very, very close call. So "Close Encounters" saved Columbia Pictures from bankruptcy – maybe. But that was a really big moment, when we finally showed the movie to the Studio, and said, “Phew, thank God, it’s going to be OK”. And it was fun, because during the production of "Close Encounters" was the same time that George Lucas was making "Star Wars" – "Star Wars" was a little bit ahead, but it was all in the same year – and Steven and George were talking all the time – they were kind of competing, and it was interesting, because I’d been asked by George to do the effects for "Star Wars". But I was a Director, I was still trying to direct projects, and I said no to George, I was trying to do something else. And after all this turmoil at Paramount I agreed to do "Close Encounters", because I thought it was different enough, and interesting enough, and it fulfilled my desire. So George Lucas says, “Well can I hire your crew?” – because I wasn’t doing anything at that moment – so George Lucas hired John Dykstra, and all of my whole crew. And they went to work at what was originally called Industrial Light and Magic – and they included my own father. WH: Really? DT: Yeah! So they did a great job, but you know making the first "Star Wars" film was very tricky, because it was a first time for a lot of those kinds of motion control effects, and it was a very close call – they were trying to do front projection for "Star Wars", where they’d have plates out the windows of the spacecraft – nothing worked, and it turned out to be a bad idea. And so they had to switch gears at the very last minute and go for blue screen compositing and optical printing. Everything turned out fine, but it was a very close call. WH: So do you regret rejecting "Star Wars"? DT: No, not at all, I’m very friendly with George, we’ve gotten along well over the years, and since it became an opportunity for me to do "Close Encounters", everything turned out just fine. I think my personal aesthetic photographically was much more appropriate for "Close Encounters" than "Star Wars". "Star Wars" in a way was more like the same as "2001": you know, flight spacecraft, black stars – that was kind of not as interesting. WH: I prefer "Close Encounters" because it’s more scientific; "Star Wars" is fantasy. DT: Well you know "Close Encounters" is actually based on reality – you know the whole story about Jacques Vallée? WH: Which one? | |

DT: Well "Close Encounters" – remember François Truffaut plays this French UFO

Researcher, named Lacombe? I found out many years later that that was

actually Jacques Vallée, a French UFO Researcher – he’s become a good friend

of mine. And he had written many books about UFO phenomena, and events that

happened back in the fifties and sixties. And Spielberg read all these books

– he wrote the screenplay for "Close Encounters", based a lot on Jacques Vallée’s stories – which were always sold as fictional stories, but they

were true stories...if you buy the whole UFO phenomenon. I think Jacques

Vallée is an incredible, wonderful, believable person who had a UFO

encounter when he was 11 years old in France – changed his life totally. So

he became one of the most, if not the most, mature chroniclers of all UFO

phenomena, to this day. DT: Well "Close Encounters" – remember François Truffaut plays this French UFO

Researcher, named Lacombe? I found out many years later that that was

actually Jacques Vallée, a French UFO Researcher – he’s become a good friend

of mine. And he had written many books about UFO phenomena, and events that

happened back in the fifties and sixties. And Spielberg read all these books

– he wrote the screenplay for "Close Encounters", based a lot on Jacques Vallée’s stories – which were always sold as fictional stories, but they

were true stories...if you buy the whole UFO phenomenon. I think Jacques

Vallée is an incredible, wonderful, believable person who had a UFO

encounter when he was 11 years old in France – changed his life totally. So

he became one of the most, if not the most, mature chroniclers of all UFO

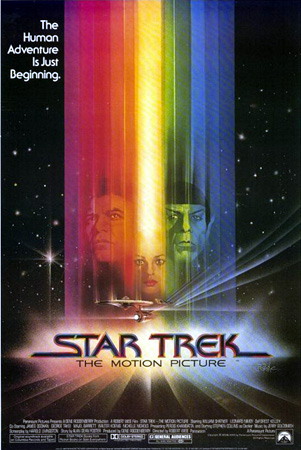

phenomena, to this day.So anyway, that’s the story of "Close Encounters" as real – so the whole idea of that whole story, maybe that really happened. WH: Do you believe in UFOs? DT: Oh yes, absolutely. WH: I think "Close Encounters" influenced a lot of movies that came after it. Important television series like "The X-Files" – you see so many elements that were seen in "Close Encounters" – again, it was a ground–breaking film. DT: It’s one of those very unusual films that treated the whole UFO / Alien Encounter thing as a benign exchange – rather than tacky, flesh-eating monsters from Mars, you know, which is so stupid. So I thought it was that kind of benign, loving, kind of amazing awesomeness that attracted me to it. I think a lot of people appreciate it, and it’s shocking to me there hasn’t been more like that. I’m intending to do one myself. WH: That sounds promising! DT: Good – I hope you like it! WH: Along came "Star Trek: The Motion Picture", for Robert Wise again, this time in 65mm – DT: Yes, the timing of it was that I was developing the Showscan film process – 70mm at 60 frames per second – which was spectacular – and I was working at Paramount, and were enthusiastic about it at the time, and I was told to develop a feature movie that I would direct, that would demonstrate this process. And that became "Brainstorm". "Brainstorm" was written for Showscan, to be this experiment, this experiential spectacle. So that’s what I was doing, and I was very devoted to that mission. And at the same time that that was happening, Paramount had got started on "Star Trek: The Motion Picture", and were having all kinds of problems. They hired Robert Abel’s company and a lot of other people to do the special effects – I was not interested in doing the special effects for "Star Trek". And they spent almost a year and half trying to do the special effects for "Star Trek". But at the same time Paramount closed my company because they didn’t believe in Showscan, didn’t believe in "Brainstorm", didn’t believe in video games. They didn’t believe in anything I was trying to do, but they wanted to keep me under contract so I wouldn’t go out and do something different for somebody else. So when they got into so much trouble on "Star Trek" they asked me again if I’d do the special effects. And I said, “OK, I will do it, but only if I can leave immediately after. Then I’ll take "Brainstorm", I’ll take Showscan, I’ll take my company and be out of my contract” – they had a six year contract on me; they wanted to keep me out of circulation. So we made this deal. I wasn’t really too eager about doing Star Trek, but I did it to earn my way out of my contract. And it was very difficult; they had no time left. There was as many shots as "Close Encounters" and "Star Wars" combined, in "Star Trek". And Robert Wise had directed the movie in such a way that there was no way around it – there was no way to change the need for that many shots. There were 650 shots, which had to be completed in six months. So we worked out a deal for my company, and John Dykstra’s company, which was then called Apogee, to join forces. They were all VistaVision and we were all 65mm – we had to make an optical printer to swap. And we took separate sequences, and we all worked 24 hours a day for six months. Seven days a week, around the clock, to get that movie done. WH: I hope you were paid for it! | |

DT: I was paid, I was paid very well – it was nothing to complain about. But

I ended up in hospital – it was major recovery; I had ulcers, all kinds of

exhaustion because I was working seven days a week, almost living in the

studio, not getting enough sleep. It was very stressful; there was a lot of

tension at the Studio, and part of the tension was that Paramount had been

threatened by the Exhibitors – do you know this story? Well, around that

time, that "Star Wars" and "Close Encounters" had been made, there was a process

called Blind Bidding, that was used largely in all theatres, but maybe even

more so in European theatres, where the theatre chains would have to pay in

advance for the right to show a certain movie before they could even see the

movie – and it was called Blind Bid. So that was a way for the Studio to get

money in advance, and so the Studio had received something like $ 35 million

in advance payments for "Star Trek". And they didn’t like blind bidding – the

theatres thought it was a horrible practice, they were being abused, they

didn’t really want to have to pay this money, they thought this illegal

actually. And so they got the word that "Star Trek" was in trouble, and might

not be delivered according to the contract, on December 7th of whatever year

– ’79 I think it was. And so the Exhibitors got together, and threatened

Paramount with a huge lawsuit. And they were actually going to close

thousands of theatres around the world over the Christmas holidays if the

movie didn’t get delivered. And they were going to use it to break Blind

Bidding – to make Blind Bidding illegal. DT: I was paid, I was paid very well – it was nothing to complain about. But

I ended up in hospital – it was major recovery; I had ulcers, all kinds of

exhaustion because I was working seven days a week, almost living in the

studio, not getting enough sleep. It was very stressful; there was a lot of

tension at the Studio, and part of the tension was that Paramount had been

threatened by the Exhibitors – do you know this story? Well, around that

time, that "Star Wars" and "Close Encounters" had been made, there was a process

called Blind Bidding, that was used largely in all theatres, but maybe even

more so in European theatres, where the theatre chains would have to pay in

advance for the right to show a certain movie before they could even see the

movie – and it was called Blind Bid. So that was a way for the Studio to get

money in advance, and so the Studio had received something like $ 35 million

in advance payments for "Star Trek". And they didn’t like blind bidding – the

theatres thought it was a horrible practice, they were being abused, they

didn’t really want to have to pay this money, they thought this illegal

actually. And so they got the word that "Star Trek" was in trouble, and might

not be delivered according to the contract, on December 7th of whatever year

– ’79 I think it was. And so the Exhibitors got together, and threatened

Paramount with a huge lawsuit. And they were actually going to close

thousands of theatres around the world over the Christmas holidays if the

movie didn’t get delivered. And they were going to use it to break Blind

Bidding – to make Blind Bidding illegal.So I was in this meeting with Barry Diller at Paramount, and he said, “I don’t care what this movie’s like: I don’t care if this movie makes any sense, I don’t care if this movie has black leader, or has missing scenes, but we’re going to deliver this movie on that date. Otherwise we’re going to go bankrupt”. I said, “Now I understand what’s motivating you!” I had to get this movie finished, and that’s why I had a really good, negotiated contract. Well everybody did it, and we got it done – it’s not my greatest work because it was impossible to do, you know, world-shaking work in a short period of time, but we got it done. WH: I guess you fully recovered from your exhaustion! DT: Oh yes! WH: If I’m not wrong, you turned 70 back in April – how do you keep up with all the new technology? DT: I’m so excited right now – it’s not a matter of keeping up, it’s that the technology we have now with digital cameras that can run at any frame rate, digital projectors that can run at almost any frame rate, now makes Showscan possible, which was very difficult back then. And so, I’m back, trying to bring to the cinema this spectacular illusion of immersiveness... you know, the spectacle of "2001" and everything, and I think it’s now possible with this new high frame rate, larger screens, higher reflective screens, and 3D. There are so many things now available to make a new kind of movie experience which is going to be more like a window onto reality – like a Holodeck or something; a high frame rate theatre. And so I’m tremendously excited about it – I’m now writing screenplays for that...and I hope movies get made, I don’t want to make them all myself, but I’d like to break ground on what I think will be a really powerful new kind of cinema experience that you cannot get on your tablet computer, or your cellphone, or even in a regular theatre – I think that the movie industry really needs a kind of shot of excitement, because people are streaming their movies, downloading their movies, and so the phrase I use now is that “the multiplex is in your pocket” – convenience, low cost, ease of use, any time you want, anything you want; and so the rationale for the multiplex cinema, which was all about that, is now changing: movie-going attendance is at a 16-year low right now, and probably getting worse. And the theatres are very worried about it, deeply concerned about it. There continues to be tremendous enthusiasm about IMAX – and I helped bring IMAX public a few years ago: I was part of the team that bought IMAX from this Canadian company and merged it with my company, raised money on the world markets, took IMAX public, raised funds – $ 350 million – and brought IMAX into the commercial marketplace. Now IMAX is the only current representative of spectacular, giant screen cinema. WH: OK, are we talking about IMAX 70mm? DT: No, we’re just talking about IMAX – WH: – Digital – DT: Yes – I mean, IMAX, whether it’s 70mm or not, they’re blown-up movies from 35mm – these movies have not been made in IMAX. Most people don’t realise that. WH: I think we’re talking about the motion pictures, not the travelogues. DT: I’m talking about the major motion pictures in IMAX – feature-length movies blown up from 35mm – or if they’re made digitally they’re blown up from a digital original. They’re not shot in 15-perf 70mm. There have been some sequences shot in 15-perf 70mm, like "The Dark Knight" – that’s beautiful IMAX, truly spectacular – so I’m a big advocate of that, but, as we all know, film is dying, rapidly: the Studios are not going to be delivering film prints of anything, starting next year – so all the theatres have to convert to digital, including IMAX, which was already mostly digital anyway – so it kind of levels the playing field: it opens an opportunity to start thinking differently about what a movie can be. That’s why I’m so fascinated by this 120 frames per second 3D, giant screen, very bright, immersive medium. I think you can tell a story in a completely different way, where the audience becomes a participant. | |

Kinepolis'

screen 9 - built to Showscan specifications. Image from 1992 by Thomas

Hauerslev Kinepolis'

screen 9 - built to Showscan specifications. Image from 1992 by Thomas

HauerslevWH: I once saw Showscan: I saw it in Brussels, in a multiplex – they had it for a short while, and I must say, it was a very unique experience – I would describe it like a live TV transmission. It was not film, but it looked completely different. This look is difficult for some cinema goers; they think it’s not right. Do you think we all have to change our point of view? DT: No, not at all. I think movies as they are are fantastic; it’s the bedrock of cinematic entertainment. So 35mm, or 2K digital, or 24 frames-per-second on a rectangular screen is the most common, solid, great medium to tell a story – love stories, musicals, everything – you name it. All works great. I’m not trying to threaten anyone; or say, “change to something else” – not at all. The nice thing about the new digital projectors is that they’re already running at 144 frames per second, just it’s not being used. So even when you see a regular movie in a digital theatre it’s running at 144 frames – it’s just that the frames are being repeated multiple times – being flashed multiple times. So it just looks like 24 frames – it doesn’t flicker anymore because there’s no shutter, but it just enables me to think about Showscan now, because I don’t have this problem of having to install new projectors – they’re already there. So I think it’s going to get rid of one of the biggest barriers to Showscan. But my feeling is that that weird texture of a movie becoming too much like live television is a problem; it is an issue. So I’ve invented – and applied for a patent on it – a very interesting approach to that, which is that I’ve been shooting experimental demonstration films at 120 frames per second, where the shutter in a digital camera is at 360 degrees, not 180 degrees, so it means everything is being captured – so if you want to take that material and reduce it to 24 frames, all you do is blend three adjacent frames together to recover the blur that’s appropriate for 24, and then you delete the next two frames. That gives you a 5 to 1 ratio between 120 and 24. So you can make a 24 frame movie from the 120 master, and it looks exactly like film – a 24 frame movie. Same blur, same difference. But – any object that’s moving in a scene, moving so fast that it starts to blur, you can actually uprez that portion of the shot – just a football, or a hockey puck, an exploding car, or a chase – suddenly ramp up to 30, 48, 60 or 120 frames per second as needed – only on that part of the scene, so the rest of the movie will still look like 24 – it’ll get rid of that problem. There’s a lot of discussion now, because Peter Jackson has been showing 48 frame "Hobbit" material – some people feel – and I say I understand it, and I’ve experienced it with Showscan – I made a film called "Leonardo’s Dream" about that, 30 years ago – which was a costume, period drama about Leonardo DaVinci – and it was very...weird, in that it felt like live theatre. It wasn’t a movie – it was a window onto Leonardo’s laboratory. And I concluded then that maybe that wasn’t the appropriate way to go. So now I know that these new digital technologies will allow a Director, as they do now in 3D movies – if a Director directs a 3D movie, some shots are a lot of 3D, some shots are a little 3D, some shots are almost no 3D: they can modulate the dimensionality as needed, for the storyteller, which is completely appropriate. Now we can modulate frame rates as well, dynamically, just like you modulate colour timing, colour grading, brightness, or loudness of sound: they’re all variable. So I think it’s possible to make a new kind of movie that still, to all intents and purposes, looks like a regular movie, but when some big action happens, it doesn’t become a bunch of blurred stuff: freeze-frame on your action sequences and you’ll see how much is lost. Blurring is a big problem, particularly on fast pans and fast action sequences – and everybody wants action sequences; not all the time, but in certain parts of the film, so it’s possible to dynamically modulate the frame rate and everything. This is totally new – it’s a radical new idea – I’m just talking about it for the first time right here. WH: So this will also eliminate things like wheels turning the wrong way, when you see a car driving? DT: Yes – it can do that also. WH: That’s very interesting – when will we see the first film with that? DT: Well I’m hoping to shoot a sequence with my film – I’m working on a science-fiction film that I hope to shoot in June or July – maybe a little 5-minute piece – and my plan is to shoot it this way at 120 frames per second, and then I will be able to print the film at 120, 60, 48, 30 and 24, so you can look at it that way. And then we can also change frame rate dynamically on an object-by-object basis, and it can also be 3D or 2D. So – the design of this idea is to make it completely compatible with every film process ever considered, and see if that’s a better way to make a movie...and offer something that will work just fine on your tablet, on your computer, on your iPad, whatever, but also offer something much more spectacular, particularly on a giant screen – because when you go to a giant screen, like Cinerama was, the displacement from one frame to the next can be several inches or several feet – and your eye can’t connect that together. So there’s a lot of eyestrain attended to particularly large screen movies. You can see with IMAX movies that the action is too fast; it gets very hard to watch. But if you increase the frame rate, then it’s great, it becomes very comfortable. And there’s a lot of eyestrain attended to 3D as well, because of 24 frames. So I think when people see "The Hobbit" at 48 frames they may have a weird feeling about the realism of it, but they’ll notice immediately how much better the 3D is. And that’ll be a very interesting social experiment – to see if that’ll get people back into theatres. It’s a big, big move in the right direction – and Jim Cameron you know wants to do "Avatar" 2 and 3 in 60 frames. WH: Which would be Showscan speed – Showscan analogue! DT: Yes! | |

WH: That brings me back to "Brainstorm", which you’ve already said was

intended to be shown in Showscan, at least the dream sequences. The reason

why that didn’t come about was because the cinema industry resisted? WH: That brings me back to "Brainstorm", which you’ve already said was

intended to be shown in Showscan, at least the dream sequences. The reason

why that didn’t come about was because the cinema industry resisted?DT: It was two things: everybody who saw Showscan thought it was fantastic; I mean they just loved it; a unanimously positive response. The problem was that I couldn’t get the Studio to make the first film, because they said, “We will only make a film, and spend millions of dollars making a film, unless there’s thousands of theatres equipped to show it. So we go to the Exhibitors, and we say, “OK, would you like to set up the theatres, with the projectors”. And they say, “Well, we would, but only if all the movies were made that way”. And so it was Catch-22, blaming the other guy. And I tried for a couple of years to make it happen, and I realised it was just about impossible. There was a big barrier between the Exhibitors and the Studios, and I just couldn’t make it happen. So I had to give up, and agree to make "Brainstorm" conventionally. So I went 70mm and 35mm and changed the aspect ratio, changed from mono sound to stereo sound, back and forth – I did as much as I could within the context of not having Showscan. But it’s been my dream, for years, a long, long time, to make a movie in a process like this, that changes the relationship between the audience and the movie – where the audience is in the movie; not looking at the movie. That’s what "Brainstorm" was about – getting inside someone else’s head. So we can do that now – because the system’s all there: the cameras are there, the projectors are there; we just need to change the servers a little bit – give them a little bit more data. WH: Did some original Showscan footage go into "Brainstorm"? DT: No – never. WH: So the scene with the truck on the road – everything was done in Super Panavision? DT: Yes. WH: In that film I especially like the music score by James Horner. Can you tell us a little bit about how that came about? DT: I can’t remember when I first met James, but he was a very young man when I first met him, and I met him when he was working on a score for some other film – I can’t remember what it was – but we met, and I really liked him. And he really liked me, so he agreed to do the score for "Brainstorm". And we wanted to do some musical things – kind of unusual, exploratory – and MGM said that was fine, and it was just a fantastic experience, and I’d like to work with him again. You know, Steven Spielberg always works with John Williams – well I’d like to always work with James Horner! | |

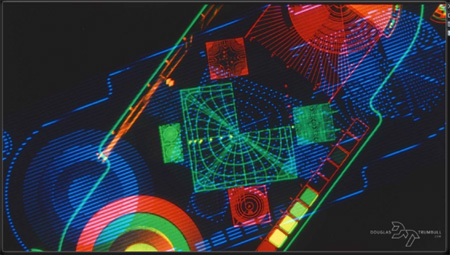

Artwork

from "Brainstorm" main titles. From Douglas Trumbull's page Artwork

from "Brainstorm" main titles. From Douglas Trumbull's pageWH: Was it just that one film you worked on together? DT: Yes, because I haven’t made any films since "Brainstorm" – the whole tragedy of Natalie Wood dying during "Brainstorm" just completely discouraged me. I was already discouraged that I couldn’t get Showscan happening, and then to have my actress die under very, suspicious circumstances, let’s say, and I had an extremely challenging time to get the movie finished. The Studio didn’t want to finish the movie, they wanted the insurance money, and I was not welcome at the Studio anymore, I was not welcome by Management at the Studio anymore. And I’d already had so many experiences with Studios prior to that, you know with my development and so forth, I just decided I had enough of that, I can’t take this; this is too unpleasant, too disturbing, and I decided, well I’ll just have to stop directing. I had to do something; literally, I just had to move out of LA and start over again. So I moved to Massachusetts and set up a little studio there, and it didn’t take long before "Back to the Future". And I thought, ah, this is good, because I invented the simulator ride, at Future General years before, and it had developed into this new business, and so they were going to do this big ride, and Steven Spielberg was involved with Universal with this ride. Friends of mine had been working on it, and they couldn’t make it work – so I got a call from a friend who said, “They’re looking for a Director for the "Back to the Future" ride, to fix it”, and I said, “I’m here; I’d love to do that”. | |

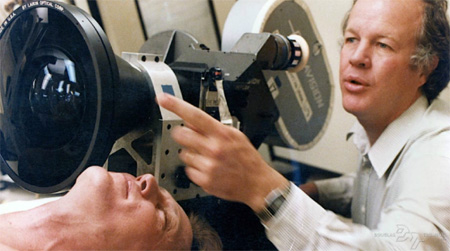

Filming

of "Brainstorm". From Douglas Trumbull's page Filming

of "Brainstorm". From Douglas Trumbull's pageSo I talked to Steven, and I kind of know how Steven directs; I know how Steven thinks. And I pitched an idea for the ride, that I thought it would be in keeping with the trilogy of films that he had produced with Bob Zemeckis, and I thought would be a really terrific ride. But I also had the technical understanding of the whole simulation – the relationship of motion to a movie. And of the fact it was going to be IMAX projection, a flight simulator-type ride. And I thought it was a really interesting moment, to explore this same concept, the whole idea of putting the audience inside the movie – was what that ride was all about. You’re in the movie – you’re not looking at a movie, you’re inside the movie, you’re feeling the movie, you’re tasting the movie, it’s all around you. And that was just a wonderful, spectacular project. It was hugely successful – probably made $1 billion for Universal – played for almost 20 years, in all three of their parks – and a lot of people felt it was the best theme park attraction ever made. Did you ever see it? WH: No – DT: Well, you have to go there! There are only three places to see it, so – WH: I’ve never been to the USA...I hate long flights! | |

Filming

of "Brainstorm". From Douglas Trumbull's page Filming

of "Brainstorm". From Douglas Trumbull's pageDT: Really? OK, anyway it was a wonderful experience, but it was also disappointing that the cinema industry, that I feel that I’m part of, did not recognise that the "Back to the Future" ride was a cinematic experiment. It was like when the Lumière Brothers had the train coming into the station scene, which is in "Hugo" – that was such a big moment in Cinema that everybody freaked out. So I think the "Back to the Future" ride for me is a big moment in Cinema, because it actually allows the audience to participate in the movie. Even though it’s only four minutes long, it’s an incredibly kinetic, powerful experience. But it was limited by 24 frames, and blurring, and strobing, and a very dim image, and other, technical challenges at the time. But now we can do it. WH: There’s a chance for upgrading it! DT: Absolutely...they’ve turned it into something else now – into a Simpson’s ride...kind of silly – it’s OK, doesn’t really matter much. To me, there’s a continuity to the theme of my work, which is to try to see if we can’t get closer and closer to using the cinema to create its own immersive, powerful personal experience for the audience. Through direct experience rather than through empathy for characters. I think that’s an interesting challenge; that’s what I’m all about...I’m still trying to get there. | |

WH: The whole cinema industry is going digital now, but if I’m not mistaken,

you did some 65mm on "The Tree of Life"? DT: No, what we did on "Tree of Life" – I don’t hire out as a special effects

guy, but Terry Malick is an old personal friend of mine – we were

contemporaries, the same age, we grew up as Directors together – and we were

talking two years ago about this passion for this "Tree of Life" project. And

his disappointment with computer graphics to create anything really

beautiful, organically cosmic, like we did in "2001" or even "Close Encounters"

– which were all water tank tricks with paint and high-speed cameras – and I

said, “Well we’ve got high-speed cameras that’ll go 1000 frames per second

now; effortlessly; just like that. And what if we did effects for "Tree of

Life" using high-speed cameras and water tanks and turbulence and liquids and

flows – try to create these what I call ‘organic effects’, that would be

unpredictable”. And he loved that idea, because Terry is all about what he

calls “the dowse” – trying to create a circumstance where something

unexpected will happen, during the photography. I mean if you read about

Terry’s movies, you’ll see that’s the whole theme that’s going on. So he’s

constantly, even in live action shooting, he will get his actors all

prepped, and everybody knows the scene, they’ll know the story – but he’ll

suddenly inject some unexpected other character, or situation, or a

disturbance in the scene, to get the actors to become spontaneous – to get

to another level. DT: No, what we did on "Tree of Life" – I don’t hire out as a special effects

guy, but Terry Malick is an old personal friend of mine – we were

contemporaries, the same age, we grew up as Directors together – and we were

talking two years ago about this passion for this "Tree of Life" project. And

his disappointment with computer graphics to create anything really

beautiful, organically cosmic, like we did in "2001" or even "Close Encounters"

– which were all water tank tricks with paint and high-speed cameras – and I

said, “Well we’ve got high-speed cameras that’ll go 1000 frames per second

now; effortlessly; just like that. And what if we did effects for "Tree of

Life" using high-speed cameras and water tanks and turbulence and liquids and

flows – try to create these what I call ‘organic effects’, that would be

unpredictable”. And he loved that idea, because Terry is all about what he

calls “the dowse” – trying to create a circumstance where something

unexpected will happen, during the photography. I mean if you read about

Terry’s movies, you’ll see that’s the whole theme that’s going on. So he’s

constantly, even in live action shooting, he will get his actors all

prepped, and everybody knows the scene, they’ll know the story – but he’ll

suddenly inject some unexpected other character, or situation, or a

disturbance in the scene, to get the actors to become spontaneous – to get

to another level.So we were trying to that with the effects – optically something would happen in front of the camera that none of us could even plan, and that was just a lot of fun. It’s an art movie, so to speak – it’s certainly not a mainstream, action-adventure like Transformers or anything – it’s the anti-Transformers. So I was delighted that it was so well received; it made me comfortable that there’s – I think there is still a big audience for intelligent movies – thoughtful, intelligent movies. These superhero movies are OK – I have no problem with them – but I think there’s an audience who like a little bit more gratification, a little depth, a little more important ideas and thoughts. WH: The science-fiction project you’re developing currently, is it more like that then? DT: It is – I have my own limited intelligence, but I’m trying to tell a story that I think is as possible and as intelligent as "2001"...based on scientific reality, astronomical reality, space and time reality...it’s not a monster movie, there’s no aliens attacking – but it will touch on alien contact, and issues that are all starting to come up now. I mean it’s so fascinating that we have things like the Kepler spacecraft after finding that there are probably 100 billion habitable planets – I mean that’s mind-boggling! So that’s scientific evidence that you can see on any bookstand – you can buy Telescope magazine, or Scientific American, or anything; you can read online that the propensity for life in the Universe is enormously big – and there’s some reason why we don’t know that. I think that’s really interesting, and if you poll people in the world, most people will say that they believe there’s life in the Universe. But there is a big stigma attached to UFOs and aliens; in the sense that it’s been so demonised in movies, and so trivialised, in science-fiction movies, that nobody who has an academic credential will touch the subject – it’s an interesting thing. So astronomers, physicists, astro-physicists, people in the space program, people in NASA – they all believe in life in the Universe but nobody wants to talk about UFOs – because they’ll lose their job. They’ll lose tenure, they’ll be ridiculed, they’ll be locked up, become a laughing stock – so no-one wants to talk about it. I think it’s a really huge and interesting story – and I’m not afraid of it, because I don’t have tenure and I’m not a scientist – I don’t have anything to lose! So I think it’s really fun territory this, very fertile ground. You can see hundreds of thousands of early great science fiction stories that deal with contact with other planets, the future, time travel, space-time continuum issues, quantum physics – I think it’s fascinating; I think the audience is really very smart. We have the most technologically-astute audience that has ever lived on this planet – and Hollywood treats them like they’re stupid. So, there’s plenty of room to do something different. WH: It sounds very promising – you have the screenplay ready. Now you are going to do a test sequence of Showscan Digital, and then you will be looking for finance? DT: I don’t really call it “Showscan Digital” – it’s not technically the name of this thing. I have an arrangement with Showscan, because they actually paid for some of these early tests – this whole idea of embedding high frame rates and low frame rates is the Showscan Digital concept, but the 3D application of it into the higher frame rates is not Showscan Digital. I haven’t even named it yet – it’s a whole different thing – I have two separate patents applied for, just to have some business control over it. I’ve been out of the movie business for thirty years. I’m not on anybody’s A-List as a Director, or Writer, or Producer or anything. But I am trying to re-appear on the scene because I really have a passion to do something important. And because of this disconnect between the Studios and the Exhibitors, there’s really no technological undercurrent that pins the movie business together; there’s just suppliers of cameras, there are suppliers of projectors, and there are people that use them; Studios that want to sell a lot of tickets on a long weekend – and so I don’t expect the Movie Studio to call me up wanting me to direct a movie, because I’ll probably say no anyway. And so I’m crazy enough to believe that we can actually somehow jumpstart a new industry...that I tentatively call this idea of a HyperCinema: where you would go to a place that’s not even a movie theatre. I don’t call it a movie theatre: it’s like going to the Holodeck; it’s like going to see Cirque du Soleil; it’s like going to the theatre to see a Broadway show. You know it’s going to be a live event, or a circus, or something that’s going to happen that’s extraordinary. And so I think we need to bring some Showmanship back in, it has to be special reserve seat tickets, it has to be a spectacle, of epic proportions; so different from anything you would expect to see in the movie theatre. So it will be higher priced, worth it, and totally different. And I don’t know where the funding ticket is going to come from; Silicon Valley, or some Billionaire who’s interested in the future of space travel; I don’t know...it’ll come from somewhere else. WH: I hope you’ll succeed with it – DT: I’m trying – WH: – because I’m excited to see it! DT: I’m so excited right now, it’s so much fun. And it’s a really great time. | |

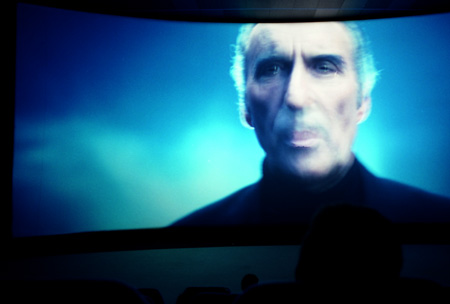

WH: There have been some short films produced in Showscan; what has happened

to the negatives, the sound masters? Filming

of "New Magic". From Douglas Trumbull's page Filming

of "New Magic". From Douglas Trumbull's pageDT: They’re all there – Showscan has an Archive of all those negatives. One of the interesting things that’s happening right now is that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences wants to archive at least two of them, Showscan original negatives, because there was a very important film I made called "New Magic", which was my first real Showscan experimental film, and it’s admired by a lot of people who remember seeing it, because it showed for the first time you could put something on the screen that would be indistinguishable from reality. That had never been done before. I was experimenting with a lot of things – this was many years ago – but I hired Nicolette Sheridan, you know, who’s been a big star on "Desperate Housewives" – she was very young, very beautiful, an untrained supermodel – and we hired her to look into the camera, about a foot away, like this close [Gestures]...and try to seduce the audience. And it was freaky, actually. And then I hired a hypnotist, to do a hypnotic routine; try to hypnotise the audience – and we could hypnotise the audience. And we hired Ricky Jay, who was one of the greatest card trick manipulators, to do card tricks in front of the audience – wow. So we were going into this new kind of “direct contact” kind of filmmaking experiment; that’s what "New Magic" was all about. | |

From

the filming of the first Showscan demonstration film: "New Magic". Image from the Showscan brochure. From

the filming of the first Showscan demonstration film: "New Magic". Image from the Showscan brochure.And I did this funny scene, in "New Magic", which has become kind of a historical moment in movies, where I knew that people coming to see this demonstration film were coming to Doug’s office to see Doug’s film, Doug’s screening room, Doug’s demonstration of Showscan – that was what I knew they knew. So I purposely made a really bad movie. And so we shot this horrible little 35mm documentary film, of a kind of a fireworks show being set up: terribly directed, terribly shot, terribly edited; we scratched the print, we spliced it out-of-frame, we ripped the perforations off one side, and then projected it crooked and out-of-focus. So it was a movie of a movie – I had a big screen, but there was just a small movie in the middle of the screen, and it was bad. And then it burned – and then you hear this clank in the back and you see the shutter douse on the projector. And then the house lights came up...but they’re not real house lights – they’re a movie of houselights. And then you hear the Projectionist screaming, in the projection booth – he’s freaking out that he broke the film – and you hear him run around the theatre on the surround sound, and then he opens the door behind the screen, and comes up to the screen from behind, with a flashlight, and starts talking to the audience, explaining that he’s sorry, he made a mistake, he’s got another print back there somewhere and he’s gone rummaging around – and so people like, seasoned movie professionals – like Steven Spielberg, he’s a really good example – he’s a friend of mine – came to see my demo film. And so when that happened, he got up out of his seat, shook my hand and said, “Doug, you know, call me when you get it fixed”. And then he just started walking across, and I was just waiting: “He’s going to understand this in a minute” – and he got to the door and looked sideways to the screen and realised it was just a two-dimensional movie of this Projectionist. | |

Sir

Christopher Lee explaining the Showscan concept to the audience in "New

Magic" on the curved screen at "Les Pavillons de la Communication et de

la Créativité" in Poitiers in France, 1992. Image by Thomas Hauerslev Sir

Christopher Lee explaining the Showscan concept to the audience in "New

Magic" on the curved screen at "Les Pavillons de la Communication et de

la Créativité" in Poitiers in France, 1992. Image by Thomas HauerslevAnd so it was that moment, that to me was a moment in movie history as well. That we would create this illusion of something really happening, live, in the theatre at that moment. That’s where I’ve been trying to go ever since – it’s been a huge setback to not be able to do Showscan, a huge setback not to be able to do "Brainstorm" the way I wanted, a huge setback for Natalie Wood to die – I just had to retrench, and rethink. So I’ve decided that now we have digital projectors, I realised about three years ago that these projectors were running at 144 frames per second – I’m trying to think, “Well why’s that?” – because they’re triple flashing the left and right eye for 3D movies. I thought, “Well, that’s way better than Showscan – it’s already there”. So I started talking to the projector manufacturers, and I started talking to camera manufacturers, and I asked, “Can we go 120 frames?” – “Oh yeah, that’s easy” – “Can we shoot at 120 frames?” – “Yeah, that’s easy too”. So I started this experiment, but it calls into question the whole cinematic language. Not that it’s going to make it obsolete – it’s just different; that’s all it is: different. WH: So with a film becoming that real – have you ever been approached by the military, similar to what happens in "Brainstorm"? DT: Actually I haven’t been approached...well I have...I will say I have. There are other initiatives going on – there’s an interesting crossover, because I work with Christie Digital’s projectors, and I deal with a different division of Christie because it’s the simulation division that makes special projectors for flight simulators; training simulators and things like that. So there’s a whole different culture of that world, and there has been a huge amount of recent interest in what I’ve been doing in training. And I’m just a little bit cautious about training people to kill more effectively...it just disturbs me. I’m sure it’s going to happen; I can’t make it not happen: if it’s a profitable way to go, it will. If it can train people to save lives, or live longer, or save the planet from destruction, then I’m all for that. But I just feel like I need to explore what we can do with this medium. I’m a member of a new group called the Overview Institute – there’s a thing called the Overview Effect, it’s a book written by a man named Frank White, who was interviewing astronauts coming back to Earth, who all were completely – their minds were expanded by looking at the Earth from Space. And they said, “Woah, we’re on this planet that’s in the middle of nowhere, and it’s very precious, and it’s very beautiful – so why are we having all these wars; why do we have borders; why do we fight over everything? They just came back with this changed view of Mankind, of Earth as an issue. And Edgar Mitchell, who was one of the Apollo astronauts, formed this thing called the Noetics Institute, and he’s on the Board of the Overview Institute. Our objective is to see if we can give people that kind of experience – a profound experience of our planet as a precious jewel, in the void – and see if that will help change people’s political views, or environmental views, or help solve global warming, or all the other things that we’re doing to basically use up this planet. You read just this last month about this new company called Space Resources, which is planning to mine the asteroids – have you read about that? I mean, it’s for real! These people – multi-millionaires, including Jim Cameron and some of these people involved in the new space movement, are planning to mine asteroids, to try to get more raw materials, to keep Earth going. It’s happening! WH: It sounds like a science fiction movie! DT: Exactly! But see, that’s the whole thing; that it’s not science fiction, it’s science fact. So I think if you can make that leap of faith, and say, “Let’s not make a movie about some experience...let’s have the experience – directly. That’s where I’m trying to go. And believe me, there is not any other Producer or Director or Writer I could talk to, about that – WH: You’re a pioneer – DT: – I’m a pioneer; OK, that’s my life, I’ll just keep doing it until I do it. So I’ve built my own studio, I have my own screen, I have my own stage, I have my own projectors, I have everything, just about ready to go. I’m looking for informed, innovative funding, from some wealthy individual or company who sees the vision of all this, and sees not only the value of it, but the profitability of it – I think it’d make a huge amount of money; I think it’s a no-brainer about making money. But it’s completely outside the mould of what Producers, Directors and Exhibitors think is a movie. It’s another conundrum. So that’s why I go around trying to tell everybody what I’m trying to do; so the story gets out, and people talk about it. WH: Well I wish you every success with it! DT: I appreciate it, being on camera [Gestures to camera]. | |

WH: I wanted to ask you something else, because it’s something since the

arrival of digital projection in the cinemas – everybody is saying, “Digital

can never look as good as film” – WH: I wanted to ask you something else, because it’s something since the

arrival of digital projection in the cinemas – everybody is saying, “Digital

can never look as good as film” –DT: – That’s not true. WH: – and some say, “35mm cannot be beaten by digital”, or, “If it’s 4K it’s not enough; maybe if it’s 8K it reaches 70mm”. What is your opinion on that? DT: I concluded, having been totally familiar with 70mm, and IMAX, and every conceivable kind of screen, every medium, I’m absolutely confident that the digital image has caught up with film – is now going to far exceed it – in terms of frame rate, resolution, steadiness, brightness, colour saturation – you know laser projectors are moving too – everything is happening, which has tremendous upward mobility. The digital thing just gets better – it’s Moore’s Law: doubles in power every eighteen months. And so that’s not true. Film is also, as much as it’s been a beautiful artform all these years – I’ve nothing against film – it’s a very polluting thing, it’s petrochemical: there’s a lot of chemicals involved in the process of making the film that’s toxic...and digital’s not toxic. And it doesn’t take a lot of energy; it doesn’t take a lot of shipping. And there’s a lot of other things about it too. So I’ve gone totally digital; I’m not interested in film at all. WH: One of the issues is, will digital survive Mankind? DT: Probably – that’s another good science-fiction story! WH: Because as you know, data storage media are not there forever – you have to copy your files every five years or so. DT: There’s a lot of new – I saw at NAB, just last month, holographic storage – it’s a reality. It has at least 100 year archival perpetuity – as good as any photographic material that ever was. There are other technologies in the pipeline now that will be archival. So that gives me some comfort. But I thought you were talking about the fact that the – singularity is going to happen and we’re all going to be subsumed by digital intelligence, which I think is a more likely scenario... WH: Like "The Terminator" – DT: Yeah – it’s pretty weird. WH: People are always relying on digital technology: they think they have to push the button and everything works. But sometimes it’s very tricky – DT: Yes – well, there’s kind of dumbing down of humanity that’s happened as a result of that...because people are enabled by all these digital technologies, that make manual labour obsolete – it’s one of the big problems in society right now, there’s no jobs because nothing needs to be made – it’s all robotically-produced. So there’s huge impact on electronics and these technologies on keeping our world going. But it doesn’t really get to the point – it probably won’t. It’s very scary. And we’re over–populating this planet way beyond its capacity. There’s a lot of big social issues. | |

WH: So among all the films you’ve worked on, is there any particular film

you liked especially? WH: So among all the films you’ve worked on, is there any particular film

you liked especially?DT: I still like "2001"; as a young man – as a man now – I feel that was the most interesting movie, that touched on the deepest, most profound ideas. On missions, omnipotence, infinity...big issues. You don’t see that in a monster movie. And it’s really sad to me that I don’t see many like that. So that was a big moment for me, it was great to be involved with it, I’m very proud of it, and it’s been disappointing that things like that haven’t happened more often. And I’d like to help – I’m trying to do my part to help make that happen. I think that there’s a very intelligent audience that I’m talking about that’s very underserved and would love to see something more like you know, "Tree of Life", beyond. Terry is working on another film that I’m helping on too, called "The Voyage of Time", which will be more of that. My film is much – it’s different in the fact that there’s a real story, it’s scientifically-formed story. And there is drama and there’s plot, and there’s action and a whole lot of other stuff, and it’s a very big idea. WH: Do you have a title for it? DT: Yes, but I can’t tell you. WH: OK! DT: – The title gives too much away. WH: – I understand. | |

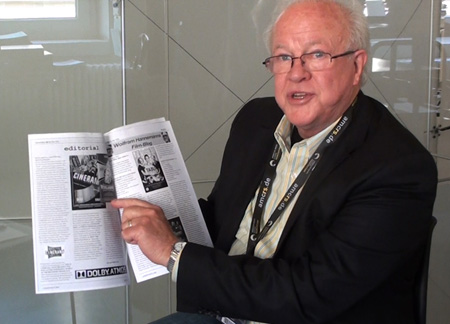

Douglas

Trumbull as he discovers mention of the Cinerama DVDs in Laser Hotline's

newsletter. Photo (c) Wolfram Hannemann. Douglas

Trumbull as he discovers mention of the Cinerama DVDs in Laser Hotline's

newsletter. Photo (c) Wolfram Hannemann.DT: I will probably talk about it some time in the next few months. Because there’s this other weird phenomenon these days – promoting a movie, or letting your audience know you’re working on something – and it really wants to be involved. It’s just a really good, social media kind of thing – Peter Jackson has a blog every month about the making of "The Hobbit" – so people feel like they’re behind the scenes, they’re part of the creative process, can see what’s going on. So there’s nothing lost, to "The Hobbit", by seeing behind the scenes, so I think that kind of social process is really good. And I’ll be doing that, sometime soon. Because I think that working with a major Studio and spending $40 million on prints and ads to get people’s attention – it’s not the way to get people’s attention. You get people’s attention by telling them a real story – not by paid advertising. And so it’s a completely different world that way. Digital media has fewer barriers between the Producer and the Audience. I really like that. WH: We’ll keep our eyes open for your website, and for your blog! Thank you! | |

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |

Wolfram Hannemann: So, good morning Mr. Trumbull,

thank you very much for taking your time to talk with me –

Wolfram Hannemann: So, good morning Mr. Trumbull,

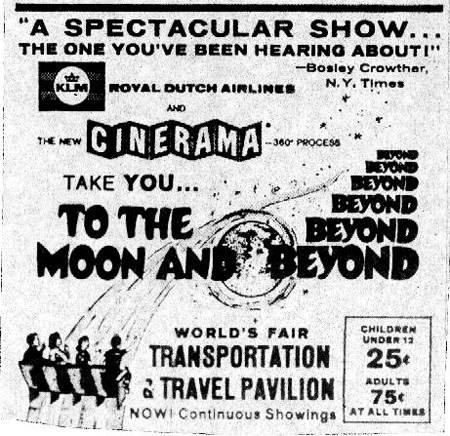

thank you very much for taking your time to talk with me – WH: I understand that "To the Moon and Beyond" was filmed in a process called

Cinerama 360 –

WH: I understand that "To the Moon and Beyond" was filmed in a process called

Cinerama 360 –  WH: It was supplied by Cinerama?

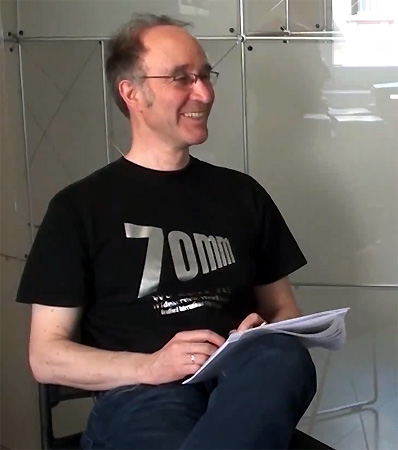

WH: It was supplied by Cinerama? Wolfram

Hannemann in May 2012 interviewing Douglas Trumbull

Wolfram

Hannemann in May 2012 interviewing Douglas Trumbull