The Bat Whispers | Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Milestone Film, New York | Date: 19.02.2011 |

Milestone Film & Video presents

Roland West’s Milestone Film & Video presents

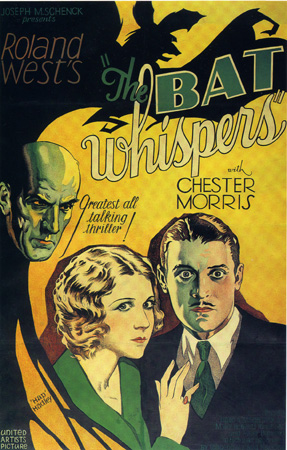

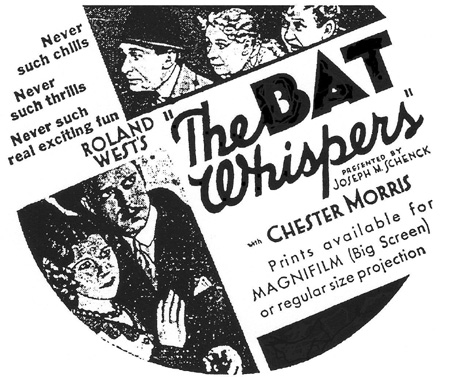

Roland West’s"The Bat Whispers" A Comedy – Mystery – Drama The raided bank! The haunted halls! The hidden chamber! The flitting Omen of Ill! The ghostly shades! The disguised strangers! The hysterical maid! And the stirring tempo Of a thousand terrors, Gasps and LAUGHS! — from the 1930 ad campaign “Now you think you’ve got me, eh? There never was a jail built strong enough to hold The Bat. And after I’ve paid my respects to your cheap lock-up, I shall return, at night. The Bat always flies at night — and always in a straight line.” — The Bat | More in 70mm reading: The Bat Whispers in 65mm Magnified Grandeur The Rivoli Theatre Magnifilm Kevin Brownlow Interview - Part 1 7. Todd-AO 70mm-Festival 2010 The Bat Whispers press notes PDF Internet link: A Milestone Film Release P.O. Box 128 Harrington Park New Jersey 07640-0128 USA Phone +1 (201) 767-3117 Fax +1 (201) 767-3035 • Email: milefilms@aol.com www.milestonefilms.com |

Credits & Cast | |

|

The Bat Whispers.

USA. 1930. Black & White. 85 minutes.

Directed by Roland West.

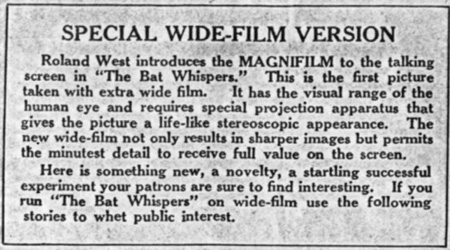

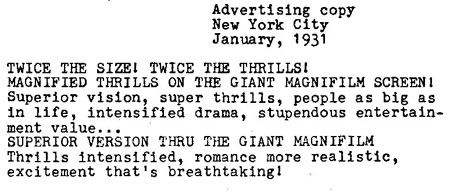

Shot in the 65mm Magnifilm process.

Aspect ratio: 2.13:1.

Restored in 35mm widescreen by the UCLA Film Archive with the assistance of the Mary Pickford

Foundation.

Special thanks to Matty Kemp, Linwood Dunn, Scott MacQueen, Ralph Sargent and YCM

Laboratories.

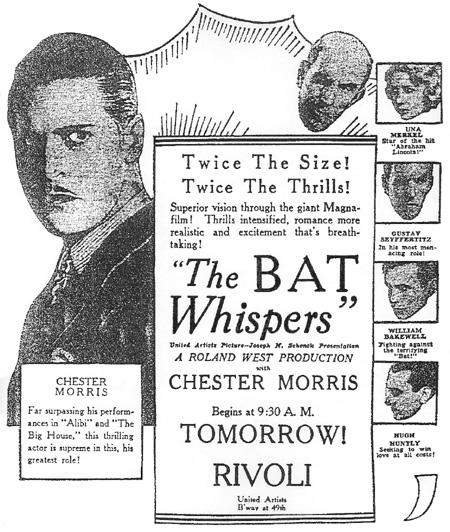

Funding by AFI/NEA Written, Produced and Directed by: Roland West. Based on: “The Bat: A Play of Mystery in Three Acts” by: Mary Roberts Rinehart and Avery Hopwood. Also based on the novel: "The Circular Staircase" by: Mary Roberts Rinehart. Cinematography by: Robert Planck. Cinematography supervised by: Ray June. Assistant cameraman: Stanley Cortez. Special photography by: Edward Colman and Harry Zech. Special technicians: Charles Cline, William McClellan, Harvey Meyers. and Thomas Lawless. Film editors: James Smith and Hal C. Kern. Set Design: Paul Roe Crawley. Miniatures & special effects: Ned Herbert Mann. Sound technician: O. E. Lagerstrom. Assistant director: Roger H. Heman. Dialogue director: Charles H. Smith. In Charge of sound: J. T. Reed. Musical Director: Hugo Riesenfeld. Production associate: Helen Hallett. Make-up: S. E. Jennings. Presented by: Joseph M. Schenck. Distributed by: United Artists. Produced by: Feature Productions-Art Cinema Associates. Released November 13, 1930. Chester Morris (Detective Anderson), Una Merkel (Dale Van Gorder), William Bakewell (Brook Bailey), Grayce Hampton (Cornelia van Gorder), Maude Eburne (Lizzie Allen), Gustav von Seyffertitz (Dr. Venrees), Spencer Charters (The Caretaker), Charles Dow Clark (Detective Jones), Ben Bard (The Unknown), Hugh Huntley (Richard Fleming), S.E. Jennings (Man in black mask), Sidney D’Albrook (Police sergeant), De Witt Jennings (Police captain), Richard Tucker (Mr. Bell), Wilson Benge (The Butler), Chance Ward (Police Lieutenant). | |

The Restoration

| |

For many years, the only known material for The Bat Whispers were 16mm prints owned by

collectors. Fourteen minutes short and lacking the widescreen effect, it barely represented Roland

West’s grand achievement. When Robert Gitt of the UCLA Film Archives decided to restore The

Bat Whispers he located the existing elements at The Mary Pickford Company in Los Angeles.

Pickford had purchased the property in the late 1930s with the intention of remaking it with Lillian

Gish and Humphrey Bogart. Examining the holdings, Gitt was faced with an overwhelming number

of elements. For many years, the only known material for The Bat Whispers were 16mm prints owned by

collectors. Fourteen minutes short and lacking the widescreen effect, it barely represented Roland

West’s grand achievement. When Robert Gitt of the UCLA Film Archives decided to restore The

Bat Whispers he located the existing elements at The Mary Pickford Company in Los Angeles.

Pickford had purchased the property in the late 1930s with the intention of remaking it with Lillian

Gish and Humphrey Bogart. Examining the holdings, Gitt was faced with an overwhelming number

of elements.The 35mm fine grain lavender of the 1:1.33 version was in bad shape, but the camera negative for overseas use was almost identical and Gitt preserved this version. Most remarkably, the 65mm Magnifilm master positive lavender, internegative, and optical sound negative still existed as well! But first the soundtrack had to be fixed. Shrunken and curling, the nitrate track (recorded at 112 1/2 feet per second) had to be transferred to 35mm magnetic stock by Ralph Sargent at Film Technology Company. There, the clicks and pops were removed carefully and Dolby was used in the silent moments for optimum sound. When Don Hagans of YCM first inspected the camera negative, it happily turned out to correspond to modern 65mm stock. The famed cinematographer, Linwood Dunn donated to the project a 65mm Bell & Howell printer, allowing Richard Dayton and Pete Comandini to make a direct B&W 65mm fine grain master. It was then discovered that the 65mm camera negative was slightly different from the fine grain lavender in the way the film ended. It was then preserved in both fashions and now the film corresponded to West’s final intentions as seen in the theaters in 1930. Unfortunately, back in 1930, there were less than 20 theaters around the country who could play widescreen films and most of the others were extremely reluctant to spend more money on new technology. On December 16, 1930, the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America forbade the industry “by word or gesture” to cause “the public’s curiosity to be aroused about any new invention for at least two years.” It was another sixty years before the bat whispered once more. | |

Synopsis | |

An arch criminal, the Bat, has been terrifying the district, eluding the police. A bank is robbed, and

the home of the president (which was subleased by his nephew, who believed the former to be in

Europe, to a woman,) is the center of mysterious happenings, apparently to frighten away the tenant.

The bank cashier, fiancé of the heroine, niece of the female tenant, is accused of the robbery when

he disappears. He disguises himself as a gardener to gain access to the house, because it was

believed that the money was hidden in a secret room there. The chief of detectives enters, the

nephew is killed, and the heroine is accused of the crime. A neighboring doctor emerges on the

scene and adds to the mystery through his suspicious moves. He knocks the chief of detectives

unconscious and steals the blueprints of the house, revealing the location of the secret room (for

which the nephew was murdered). A mysterious stranger appears, and then disappears. So does the

Bat. Amidst thrills, chills, and laughs, the money is found as is the identity of the Bat... An arch criminal, the Bat, has been terrifying the district, eluding the police. A bank is robbed, and

the home of the president (which was subleased by his nephew, who believed the former to be in

Europe, to a woman,) is the center of mysterious happenings, apparently to frighten away the tenant.

The bank cashier, fiancé of the heroine, niece of the female tenant, is accused of the robbery when

he disappears. He disguises himself as a gardener to gain access to the house, because it was

believed that the money was hidden in a secret room there. The chief of detectives enters, the

nephew is killed, and the heroine is accused of the crime. A neighboring doctor emerges on the

scene and adds to the mystery through his suspicious moves. He knocks the chief of detectives

unconscious and steals the blueprints of the house, revealing the location of the secret room (for

which the nephew was murdered). A mysterious stranger appears, and then disappears. So does the

Bat. Amidst thrills, chills, and laughs, the money is found as is the identity of the Bat...But don’t tell your friends! Otherwise, “he’ll be heartbroken … he goes around for days killing people without the slightest enjoyment for his work.” | |

On The Bat Whispers, by William K. Everson | |

A master thief who dresses as a monstrous bat, he haunts the corners of a rambling mansion whose

inhabitants set about uncovering his identity. The Bat Whispers had been done before as a silent

film, also by Roland West, and again since, as a lesser-known Vincent Price vehicle. This first talkie

version, despite being designed to take advantage of the temporary boom in 70mm-wide screens,

was somewhat of a flop commercially. The Bat Whispers remained resolutely a movie, being far

more concerned with pictorial inventiveness and lighting than with being a talkie—this at a time

when stage adaptations were all the rage. A great many motifs in the film directly derive from Fritz

Lang, the German Expressionist writer. The remarkably impressionistic bank robbery scene is pure

Lang, as is the black-gloved hand snuffing out the candle, a happy borrowing from Metropolis. A master thief who dresses as a monstrous bat, he haunts the corners of a rambling mansion whose

inhabitants set about uncovering his identity. The Bat Whispers had been done before as a silent

film, also by Roland West, and again since, as a lesser-known Vincent Price vehicle. This first talkie

version, despite being designed to take advantage of the temporary boom in 70mm-wide screens,

was somewhat of a flop commercially. The Bat Whispers remained resolutely a movie, being far

more concerned with pictorial inventiveness and lighting than with being a talkie—this at a time

when stage adaptations were all the rage. A great many motifs in the film directly derive from Fritz

Lang, the German Expressionist writer. The remarkably impressionistic bank robbery scene is pure

Lang, as is the black-gloved hand snuffing out the candle, a happy borrowing from Metropolis.During the late-silent/early-sound period, Roland West was a well-known director of stylish and innovative films. Casting the visual flourishes of German Expressionism across macabre story lines, he made comedic thrillers that stressed craft over craftiness. West’s penchant for technological innovation was surely sated by the production of The Bat Whispers. Having completed a silent version in 1926, he set about a sound remake, starring Chester Morris and Una Merkel. But this time it was shot in Magnifilm, a short-lived 65mm system, giving West a wide swathe of screen 22 years before CinemaScope. The Bat Whispers is set in an “old dark house” where danger lurks and the shadows are painted on the sets, à la Caligari. The story tells of a mysterious master criminal known as “The Bat” who follows a rival thief to an estate rented by a rich old woman (Grayce Hampton). A closet full of crusty characters converge on this manse only to discover that they have The Bat in the belfry. Fourteen minutes of restored footage were added to this print. There’s still plenty of screen for the screams. —William K. Everson | |

Background | |

|

The Bat Whispers was apparently the first movie to use the device of appealing to the audience at

the end of a film to keep mum about the ending. To reveal a plot such as this would be to a

disservice to a potential viewer so merely be aware that nothing is what it seems.

In 1939 Bob Kane created one of the 20th century’s great superheroes, Batman. The character Bruce Wayne was created in Kane’s own image but he turned to the classic film The Bat Whispers for inspiration for Wayne’s caped doppelganger. The shadowy bat symbol laden with mystery and the duel identity begot Kane’s Batman. Chester Morris’ jutting jaw and hooked nose set the standard for “the Dark Knight.” | |

Roland West | |

Born Roland Van Ziemer (1887 — March 31, 1951).

The American director, scenarist, and producer, was born in Cleveland, Ohio. His mother, Margaret

Van Tassel, was an actress and his aunt, Cora Van Tassel, a theatrical producer who gave West his

first role at the age of twelve in her 1899 Cleveland production The Volunteers. At seventeen he

landed his first leading part in a road company of Jockey Jones. In 1906 he collaborated with W. H.

Clifford on a twenty-five-minute vaudeville sketch, The Criminal (also known as The Under

World), a quick-change piece in which the nineteen year old West portrayed five different

characters. The sketch toured for five years before West relinquished his acting career to write and

produce vaudeville sketches – all of them apparently light stories of crime and detection. Born Roland Van Ziemer (1887 — March 31, 1951).

The American director, scenarist, and producer, was born in Cleveland, Ohio. His mother, Margaret

Van Tassel, was an actress and his aunt, Cora Van Tassel, a theatrical producer who gave West his

first role at the age of twelve in her 1899 Cleveland production The Volunteers. At seventeen he

landed his first leading part in a road company of Jockey Jones. In 1906 he collaborated with W. H.

Clifford on a twenty-five-minute vaudeville sketch, The Criminal (also known as The Under

World), a quick-change piece in which the nineteen year old West portrayed five different

characters. The sketch toured for five years before West relinquished his acting career to write and

produce vaudeville sketches – all of them apparently light stories of crime and detection.In 1915 West formed a partnership with Joseph Schenck, former general manager of bookings for Loew’s Theatres and the man who would remain West’s mentor and closest friend. With $26,000 they established the Roland West Film Corporation. Later the same year West directed Lost Souls, a five-reel melodrama starring Josie Collins as a Italian immigrant pressed into white slavery. It was sold to William Fox – the only distributor, it has been suggested, prepared to market such a film; it was released in 1916 as A Woman’s Honor. Schenck set up a production company in 1917 to make films starring his wife, Norma Talmadge. West was appointed general manager. He directed the company’s third picture, De Luxe Annie (1918), with Talmadge in a Jekyll-and-Hyde role. The same year West collaborated with Carlyle Moore on a stage play, The Unknown Purple, adapted from one of his old, unsold movie scenarios, The Vanishing Man (involving a “purple ray of invisibility” invented and used by the protagonist). Unable to secure backing, West opened the play out of town and then mounted a Broadway production with $50,000 of his own money. The Unknown Purple was a hit, and a shrewd investment of the proceeds assured West’s financial security. Thereafter he made films only if and when he wanted to, producing, writing, and directing one carefully prepared feature every year or two. Although they incorporated various genre elements – horror, science fiction, society drama, or romance – all of his films were fundamentally stories of crime or detection, characterized by justice frequently being administered in vengeful, vicious, or illegal ways. West’s 1921 release The Silver Lining, a vehicle for his wife Jewel Carmen, developed the dual identity theme of De Luxe Annie in a story about two orphaned girls. The movie told its story in flashback, and so did Nobody, another 1921 released starring Jewel Carmen as well. The Unknown Purple, West’s 1918 Broadway success, was filmed in 1923. In the movie, he perfected the “purple ray” and visibility effects that had been so costly and difficult to achieve on stage, antedating James Whale’s The Invisible Man by a decade. Truart Corporation, releasing The Unknown Purple, announced that West had signed a six-year contract with them as writer-director. In fact, the only other project he complete for them was a scenario based on a Redbook story, Driftwood, filmed by Rowland G. Edwards in 1924 as Daring Love. The following year West directed The Monster for MGM release. An adaptation of Crane Wilbur’s stage play, starring Lon Chaney. This is the earliest of West’s films that survives and, if it is typical of his silent output, shows that he was at the phase of his career no more than a careful technician who transferred plays to film in a proscenium style, stressing mood and production values rather then opening up the stage with film craft. Most of the “old house” stage thrillers and their movie adaptation were composed of varying proportions of macabre skullduggery and comic relief; The Monster is mostly comedy. There are echoes of Caligari in Wilbur’s story but not in West’s storytelling. The fondness he demonstrates here for nocturnal atmosphere, action played in long shot, and stage lighting devices like spotlights and dimmers is natural in someone so thoroughly grounded in theatre – just as the sensationalism of West’s subjects can be traced to his training in the world of vaudeville road shows. It was his screen version of Mary Roberts Rinehart’s play The Bat, made in 1926 for Joe Schneck’s United Artists Corporation, that firmly established his reputation as a master of crime and suspense melodramas. The sensation created by the play and by West’s silent film is hard to explain today, particularly since the movie has not survived, and frequent remakes of The Cat and the Canary have usurped its reputation as the fountainhead of a genre. The rapid growth of West’s film sense must be attributed to his admiration for German expressionism. Films like Variety, Faust, and Metropolis greatly influenced American filmmakers in the mid-1920s, and few analyzed their effects more carefully than West. He was so taken with German technique that he at one time planned to direct a Norma Talmadge picture at UFA’s Berlin studio, in order to study their methods first hand. The Dove (1928), from a play by Willard Mack, was an old fashioned melodrama pitting a ruthless Mexican brigand against a dance-hall girl and her lover, but West’s fist sound film, Alibi (1929), returned the director to his special milieu, the crime drama. In a retrospective review of Alibi in the (British) Monthly Film Bulletin (July 1979), Tom Milne wrote, “what matters is the vitality of West’s direction, which revels in elliptical action, exhilarating febrile camera movements, and highly stylized lighting effects.” Much of the film, Milne wrote, is told in “intricate, fluidly dovetailing sequences” and most of the dialogue scenes are superbly handled. Alibi was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture and made a star of Chester Morris, whom West kept under personal contract. West cast him next as the eponymous master criminal in The Bat Whispers (1930), an elaborate sound remake of The Bat. West paid out of his own pocket for a 65mm camera and produced the film in both standard and wide-screen versions. His camera movements have a fluidity remarkable in a sound film of that era, achieved partly through the use of a gigantic scaffold 300 feet long and 30 feet high from which the suspended camera could zoom vertiginously through space. The Bat Whispers remains a frightening film and a technical tour de force. West used miniatures, a specially designed camera dolly, painted shadows, and pinpoint editing to masterful effect. West’s plans for Morris had included remakes of the sultry Valentino vehicles The Sheik and Son of the Sheik. However, though he was only forty-three, West was tiring of production and claimed that it was only his sense of responsibility for Morris’ career that kept him in the business. Properties he held, such as Death Takes a Holiday, were sold. Other originals in development, like a modern-dress version of The Purple Mask in which the despotic villain would machine-gun the peasants, were abandoned. West, an avid yachtsman, spoke of retiring and sailing around the world. He produced an directed one final film with Morris, Corsair (1931), a bizarre amalgam of bootlegging, illicit empire building, and sadistic vengeance loosely based on a novel by Walton Green. The book was a routine thriller, but the movie, according to William K. Everson, “like most of West’s films...the plot development is far from straightforward, and the motivations often extremely involved.” Having wrapped up Corsair, West set out on his world cruise. His marriage broke up in the course of it. Louella Parsons hinted at the nervous strain the journey had placed on Jewel Carmen, reporting that two and a half years away from civilization “almost proved fatal” to her. When he returned to California, West’s attentions were absorbed by Thelma Todd, the “Ice Cream Blonde” who had provided the romantic interest in Corsair. They opened an expensive roadhouse – Thelma Todd’s Roadside Rest – on the Pacific Coast Highway and moved into a suite of rooms over the nightclub. Jewel Carmen had vacated West’s mansion on the hill overlooking the club, and West and Todd continued to keep their cars in its large garage. It was there, on a windy morning in December 1935, after a midnight shouting match, that Thelma Todd’s bruised body was discovered behind the wheel of her roadster. West narrowly escaped a murder charge, but there were also suggestions that Todd’s life has been threatened by racketeers because she had refused to let them take over the upper floor of the roadhouse as a gambling casino. In the end, the coroner’s verdict was accidental death by carbon monoxide poisoning. West retired into obscurity. In 1940 he married the actress Lola Lane. He did a little writing in the years that followed, but when he died of heart disease in 1951, he was remembered only as an oldtime filmmaker and a figure in the Todd case. West’s reputation has grown in recent years. A writer in the Monthly Film Bulletin (July 1979) said that he has the rare gift “of being funny and frightening at the same time. Standing back, tongue and cheek, to observe his own pyrotechnic display of chiaroscuro terrors, he added an extra frisson through the keen intelligence and cynical detachment which may ultimately have been his own undoing in that they put him well ahead of his time.” For Elliott Stein, he was “one of America’s supremely original visual stylists.” | |

Chester Morris | |

|

Date of birth: February 16, 1901, New York, New York, USA.

Date of death: September 11, 1970, New Hope, Pennsylvania. Real name: John Chester Brooks Morris. As the son of a well-known Broadway actor and actress, he appeared in silent films as a child, then went on the stage in his teens and was a seasoned player by the time he made his adult film debut in Alibi (1929), a performance that earned him an Academy Award nomination. Somewhat resembling the Dick Tracy cartoon character, he typically played a determined, two-fisted hero. He portrayed Boston Blackie in 13 of the series’ action films. He died of an overdose of barbiturates shortly after completing a comeback appearance in The Great White Hope (1970). | |

Gustav von Seyffertitz | |

|

Gustav von Seyffertitz ((1863, Vienna, Austria — 1943)) was a character actor of numerous Hollywood silent and sound films. After

long stage experience in Germany he came to America. During World War One he used the screen

name G. Butler Clonblough to disguise his Teutonic background and he used that pseudonym as

late as 1919, as the director of The Secret Garden for Famous Players/Paramount. He also used the

credit G. V. Seyffertitz as the director of three films for Vitagraph, all starring Alice Calhoun and all

released in 1921: Princess Jones, Closed Doors, and Peggy Puts It Over. But he was most famous as the arch-villain of many a movie, memorably as Moriarty opposite John Barrymore in Sherlock Holmes (1922) and the evil child slave owner in Mary Pickford’s Sparrows. Seyffertitz also appeared in such classics as The Whispering Chorus (1918), Barbed Wire (1927), The Docks of New York (1928), Queen Christina (1933), Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936) and Son of Frankenstein (1939). | |

Una Merkel | |

|

(December 10, 1903, Covington, Kentucky — January 2, 1986).

Una Merkel began her movie career as stand-in for Lillian Gish in the movie The Wind. After that

experience, she became a Broadway actress for a few years before returning to the movies in D.W.

Griffith’s film Abraham Lincoln. In her early years, before she gained a few pounds, she looked

like and was treated as a Lillian Gish look-a-like, but after Abraham Lincoln her comic potential

was discovered. She mostly played supporting roles, as the heroine’s no-nonsense friend, but with

her broad southern accent and her peroxide blond hair, she gave one of the best performances of a

wisecracking chorus girl in 42nd Street. But perhaps she is best remembered for her hair-pulling

fight in Destry Rides Again with Marlene Dietrich over Mischa Auer’s trousers. In 1962 she was

nominated for the Academic Award as best supporting actress in Summer and Smoke. | |

Avery Hopwood | |

|

Avery Hopwood was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1884 and graduated from the University of

Michigan as a Phi Beta Kappa, in 1905. He went to New York to seek his fame and fortune.

Although known as the ‘‘playboy playwright’’ and accused of mere frivolity, Hopwood had a

productive career as the author or co-author of 33 plays. In her memoir, ‘‘What Is Remembered,’’

Alice B. Toklas describes Hopwood and the photographer/novelist Carl Van Vechten as having

jointly ‘‘created modern New York.’’ Hopwood recalled his own original impetus, and why he wrote his first play, Clothes: ‘‘An intense admiration for the theater, a fondness for writing, and the ambition to make money, contrived to pave the way for my career as a dramatist; but the influence that focused my efforts was an article written by Louis V. De Foe that appeared in the Michigan Alumnus, when I was a student at the University of Michigan. ‘The Call of the Playwright’ was its title, and in it Mr. De Foe told of the fabulous sums that dramatists had made; the more I thought about it, the more determined I became to try my luck in this field.’’ He did, and his gamble paid off. The Great White Way was a street of many theaters then and a place to strike it rich. Commissioned in 1919 by the impresario David Belasco to make a star of ‘‘Miss Ina Claire,’’ Hopwood wrote a comedy called The Gold Diggers -- an expression he had heard in a bar and which he made a household phrase. Next, together with the novelist Mary Roberts Rinehart, Hopwood composed his most lucrative play. The Bat, a whodunit that had six touring companies within a year and broke box-office records in every region of the country. Finally, working out of what Alexander Woollcott called the ‘‘Avery Hopwood Playmaking Factory,’’ he wrote Spanish Love for Broadway that season and, together with Charlton Andrews, Ladies’ Night (in a Turkish Bath). Such titles suggest Hopwood’s style; he wrote bedroom farces with sexual innuendo just out of range of the censor and guaranteed to please. His success was of a transient kind: entertainment based on titillation, well built if lightweight vehicles designed to float a star. In 1920 Avery Hopwood was America’s most successful playwright, achieving the distinction of having four concurrent hits on the Broadway stage. By 1922, The New York Times described him as ‘‘almost unquestionably the richest of all playwrights.’’ But he never quite relinquished the dream of artistic achievement, and he could be engagingly snappish when accused of selling out: ‘‘I do not write more serious plays, for one thing, because it is too easy. I mean, it's too easy to write the sort of serious plays with which our stage, lately, has been inundated. They are written, mostly, by men who think that they think, and who pretend to solve, in the course of a couple of hours, one or more of the great problems which confront humanity. I could not do that sort of thing and retain my intellectual honesty.’’ In his last years, he spent little time in America; both artistic and personal freedom seemed constrained to him at home. Hopwood died in 1928 while swimming at Juan-les-Pins on the French Riviera. There were suspicions: he had been drunk, he had been battered by a vengeful lover, he went swimming too soon after lunch. The coroner’s verdict, however, was coronary occlusion. Under the terms of his will, and after the death of his mother, one-fifth of Hopwood’s estate was left to the University of Michigan. The will stipulated that prizes be awarded to students ‘‘who perform the best creative work in he fields of dramatic writing, fiction, poetry and the essay.’’ | |

Mary Roberts Rinehart | |

|

The career of Mary Roberts Rinehart can be broken up into a series of phases. The first was her

pulp period (1904-1908), where she wrote her first three mystery novels and a mountain of very

short stories. The first two novels are classics and are probably her best works in the novel form.

The Man in Lower Ten (1906) and The Circular Staircase (1907) are the earliest works by any

American author to be still in print as works of entertainment, not as “classics” or “literature”.

Rinehart also wrote a third, less successful novel during this period, The Window At The White Cat

(1908). Rinehart also wrote some Broadway comedies. Seven Days (1909), written with Avery Hopwood, became a runaway hit. She achieved success on Broadway and as a novelist almost simultaneously. And for the next 45 years she would remain one of America’s most popular authors. The immediate effect was a swerve into comic fiction for the next five years. She stopped appearing in the low paying pulps, and started to write for the commercially premier magazines. Much of her fiction during this period was in the form of long short stories. Her first sale to the Saturday Evening Post was The Borrowed House (1909), a long comic story about the wild adventures of some British suffragettes. The next year she created Tish, a middle-aged spinster who would be the center of a series of comic long short stories for the next 30 years. Tish and her friends Aggie and Lizzie do all the things largely forbidden to the women of their time, such as hunting for sharks and grizzly bears. Underneath the comic surface of these tales is a brilliant feminist vision. Rinehart wrote mysteries and hospital fiction as well in this period. She would next combine her hospital and mystery fiction, in two long short stories. The Buckled Bag (1914) and Locked Doors (1914) introducing Hilda Adams, a nurse who does undercover work for the police and who is popularly known as Miss Pinkerton. At this point (1914), Rinehart’s writing and career drastically changed. Rinehart largely gave up mystery and humorous fiction, and turned to straight novels instead, for most of the next 15 years. Her novels were commercially hugely successful, but critically slammed. While inoffensive morally, critics felt they represented lowbrow popular fiction. During these years, she suffered severe depression. The crime story The Confession (1917) is a grim but powerful portrait of a woman’s guilt, depression and mental breakdown. Rinehart also did write some mystery and humorous fiction during this period. The Bat (1917-1920) is a stage adaptation of Rinehart’s The Circular Staircase, written again in collaboration with Avery Hopwood. The Bat introduced some new plot complexities into the original novel, especially a master criminal known as The Bat. The founding of her sons’ publishing house, Farrar and Rinehart in 1929, and her need to provide commercial books for them to publish came with the advent of the Depression in that same year. All this, along with the death of her husband in 1932, conspired to influence Rinehart in writing much more mystery fiction during the last 25 years of her career. Her return to the mystery field, The Door (1930), is one of her poorest works. This long and interminable work, like such successors as The Wall (1938) and The Yellow Room (1945), probably damaged Rinehart’s reputation as a mystery writer. By the early 1940’s critics like Howard Haycraft were treating Rinehart’s books as old-fashioned camp. The best of Rinehart’s non-series mystery novels is The Great Mistake (1940). Here, Rinehart’s later technique is found at its finest. Rinehart’s final novel, The Swimming Pool (1952), also has its strengths and weaknesses. It is another great Brontosaurus of a novel, and many parts never jell. Yet it has a tragic grandeur of conception, especially in its finale. She lived in New York City, in an 18-room apartment until she died on September 22, 1957. She continued writing until her death, averaging about 4,000 words on a “good day.” | |

Milestone Film & Video | |

|

Milestone was started in 1990 by Amy Heller and Dennis Doros to bring out the best films of

yesterday and today. The company’s new releases have included Takeshi Kitano’s Fireworks, Bae

Yong-kyun’s Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?, Luc Besson’s Atlantis, the

documentaries of Philip Haas, and Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Maborosi. In 1999, Milestone will be

releasing the new Italian film by the director Edoardo Winspeare, Pizzicata. Milestone’s re-releases have included restored versions of Luchino Visconti’s Rocco and his Brothers, F. W. Murnau’s Tabu and The Last Laugh, Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack’s Grass and Chang, Michelangelo Antonioni’s Red Desert, Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Antonio Gaudi and Woman in the Dunes, and Kenji Mizoguchi’s Life of Oharu. Milestone will also be releasing the films of silent screen legend Mary Pickford, Curtis Harrington’s Night Tide. Milestone is also known for rediscovering, acquiring, restoring and distributing unknown “classics” that have never been available in the US. These include Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Mamma Roma, Alfred Hitchcock’s “lost” propaganda films, Bon Voyage and Aventure Malgache, Early Russian Cinema (a series of twenty-eight films from Czarist Russia), Mikhail Kalatozov’s astonishing I am Cuba and Jane Campion’s Two Friends. In 1998, Milestone will also release the “lost” films of Kevin Brownlow — It Happened Here and Winstanley. Milestone received a Special Archival Award from the National Society of Film Critics in 1996 for its restoration and release of I am Cuba. Video Magazine gave a ViVA Gold award for the company’s video release of the “Age of Exploration” series, naming it one of the top-ten releases of 1992. Five of Milestone’s restored titles (Grass, Tabu, Mary Pickford’s Poor Little Rich Girl, Clarence Brown and Maurice Tourneur’s The Last of the Mohicans and Winsor McCay’s Gertie the Dinosaur) are listed on the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry. Vice President Fumiko Takagi started with the company in 1995 and is the Director of Acquisitions and Foreign Sales. The Director of Nontheatical Sales, Megan Powers, came to Milestone in 1997. Amanda Powers, Design Intern, joined the same year. Press kit written by Amanda Bowers. Milestone would like to thank Keith Lawrence, Elaina Archer, John Flynn and Hugh Munro Neely of Timeline Films Tom Anderson and the Mary Pickford Foundation Scott MacQueen, Disney Pictures Cary Roan and The Roan Group Robert Gitt and the UCLA Film Archives Richard Dayton, YCM Labs Scott Eyman and Lynn Kalber, Palm Beach Post David and Shari Pierce | |

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 22-01-25 |