The Rivoli

|

This article first appeared in |

|

Written by: John Belton, New York, USA |

Issue 59 - December 1999 |

|

|

Further in 70mm reading: |

The First Todd-AO Cinema |

|

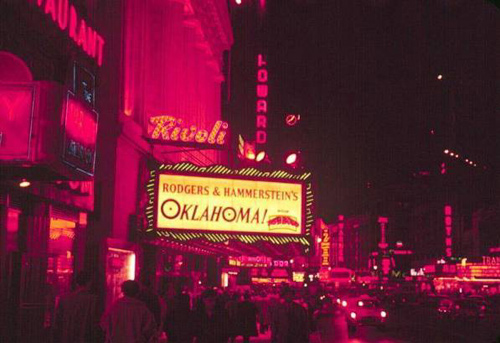

For one generation of moviegoers, the phenomenon of Todd-AO remains inextricably bound up with the Rivoli theater in New York City. The first Todd-AO feature,

“Oklahoma!”, premiered at the Rivoli on October 13, 1955 (press previews were held at the theater on October 10). Coming in the wake of

Cinerama, CinemaScope, and VistaVision,

Todd-AO emerged as the

Show of Shows. Indeed, it remained the premiere large screen format for almost a decade and helped to establish 70mm as the Rolls Royce of exhibition formats. Todd-AO's large 70mm image and wide angle lenses duplicated some of Cinerama's three-dimensional effect and sense of participation without Cinerama's famous flaws (lateral distortion, visible seams separating the three image panels, etc.). Like Cinerama, it relied on a deeply-curved screen to engulf the audience in an illusion of depth. With its six-track stereo sound, it rivalled the seven tracks of Cinerama and outclassed the more-limited range (four tracks) of CinemaScope. For one generation of moviegoers, the phenomenon of Todd-AO remains inextricably bound up with the Rivoli theater in New York City. The first Todd-AO feature,

“Oklahoma!”, premiered at the Rivoli on October 13, 1955 (press previews were held at the theater on October 10). Coming in the wake of

Cinerama, CinemaScope, and VistaVision,

Todd-AO emerged as the

Show of Shows. Indeed, it remained the premiere large screen format for almost a decade and helped to establish 70mm as the Rolls Royce of exhibition formats. Todd-AO's large 70mm image and wide angle lenses duplicated some of Cinerama's three-dimensional effect and sense of participation without Cinerama's famous flaws (lateral distortion, visible seams separating the three image panels, etc.). Like Cinerama, it relied on a deeply-curved screen to engulf the audience in an illusion of depth. With its six-track stereo sound, it rivalled the seven tracks of Cinerama and outclassed the more-limited range (four tracks) of CinemaScope.The Rivoli theatre, a Broadway movie palace which was originally built in 1917, was the perfect venue for Todd-AO, largely because of its historic concern for and association with quality in motion picture sound and image reproduction. In this respect, it is important to point out that the Rivoli was named after the rue de Rivoli in Paris. This street connected "the Louvre, France's home of pictorial art, with the Opera, her home of music" (Theatre Magazine, December 1917). In other words, the Rivoli was a site for the presentation of the "best" in motion picture sound and image. In the mid-1950s, this "best" was epitomized by the Todd-AO process. |

20.08.2008 Mr. Belton: I am a third generation NYC theater brat. Your essay has brought back a flood of wonderful memories, some forgotten, until now. I loved your piece about the RIVOLI Theater. I worked at the RIVOLI Theater, on Broadway, for four and a half years (1960 - '64.) "Alamo" West Side Story" and "Cleopatra" all were reserved seat road shows. I was the treasurer for the Beatles 1964 US tour. A year later I worked for Billy Rose at the Zeigfield Theater. '65 found me at the Shubert Theater. Eventually the Metropolitan Opera asked me to join their company in 1966 the Opening Season. I worked there, to retirement, in 1997. My Great Uncle, my Dad's Uncle, Rivington Bisland, was Box Office Treasurer for Mike Todd and Todd's film, "Around The World in 80 Days" which was premiered at the RIVOLI. |

"Roxy" Rothapfel |

|

|

The Rivoli auditorium was legendary for its acoustics. As

Joseph Kelly, former head of projection for United

Artists Theaters, pointed out, the auditorium had "excellent dialogue intelligibility." The Rivoli was originally designed to showcase Dr. Hugo Riesenfeld's fifty-piece orchestra (and, once a week, the combined orchestras of the Rialto and Rivoli, which was called the Rothapfel Symphony Orchestra, after theater impresario S. L. Rothapfel). The Rivoli was the brainchild of "Roxy" Rothapfel, who managed both it and the Rialto. It was conceived as a sister theater for the Rialto and a place where, as at the Rialto and other Roxy theaters, music would be featured. After opening the Rialto in 1916, Roxy had quickly noted the importance of music in his programming, especially the popularity of soloists, the organ, and the orchestra. Though other movie palaces of the 1910s and 1920s had stages to present stage shows and elaborate dramatic acts, the Rivoli originally had no stage. It had three

proscenia - a center one for a screen and side ones for soloists and an orchestra. A full stage was not built until 1926, when it was used to accommodate the sorts of stage show presentations that had become popular in the 1920s. Roxy moved his offices from the Rialto to the Rivoli, which was located in the heart of the theater district at 49th and Broadway and where, according to Ben Hall, he established "a pattern of personal grandeur [including a Japanese man-servant] that was to grow and grow" (The Best Remaining Seats). His lavishness apparently included expensive, personal, long distance phone calls to French race tracks to which his financial backers objected. Roxy resigned from the Rivoli in 1918, ceding his role as manager to Riesenfeld. |

|

Showcase for sound |

|

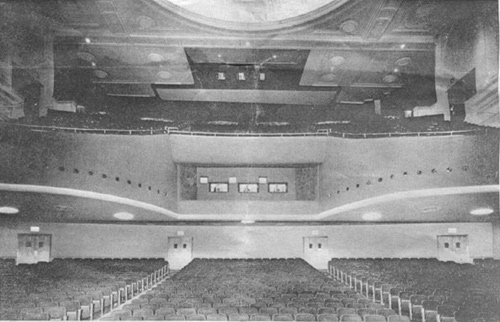

The Rivoli. Picture

from trade magazine. The Rivoli. Picture

from trade magazine.Originally, orchestral music functioned as a major attraction. The theater publicized its grand pipe organ, built by the Austin Organ Co. of Hartford, CT, as the biggest organ ever to be installed in a motion picture theater. As Motion Pictures (July 1918) noted, "'Color Symphonies' are literally played by a system of meshed and multi-hued lights whose effects blend chromatically with the symphony orchestra of sixty [sic] pieces. A novel feature of the Rivoli is 'olfactory music,' or a system of atomizers which spray perfume--oriental, clover, new- mown hay - and in accord with the orchestra, the screen and the stage settings literally imbue one's senses with the atmosphere of the play." Though not every movie palace had a compressor plant and a system of atomizers for the distribution of scents, this sort of sensory attraction was not uncommon for the period (see Townsend and Hennessey, "Some Novel Projected Motion Picture Presentations, Transactions of SMPE 12, No. 34, April 1928). As a matter of fact, the Rivoli has an extensive sound history. It was the site for Lee De Forest's demonstration of his Phonofilm process on April 15, 1923; this program featured a series of short films of vaudeville performers. In August 1924, De Forest recorded Riesenfeld's score for “The Covered Wagon” using his Phonofilm process; the score was successfully played back during "lunch" and "supper" showings of the picture (for which screenings, there had previously been only limited musical accompaniment on an organ). On February 11, 1927, the RCA Photophone system (a.k.a. the Kinegraphophone) was unveiled at the Rivoli; the demo included two reels of M-G-M's “Flesh and the Devil”, synchronized to an orchestral score, a clip of the Van Curier Hotel Orchestra of Schenectady, and a medley sung by General Electric employees. Identified with sound-on-film systems such as the Phonofilm and the Photophone, the Rivoli did not install the sound-on-disc Vitaphone system until May 25, 1929. Years later, for “The Portrait of Jenny” (March 1949), additional speakers were installed in the theater to play back music and sound effects during the final storm sequence. Twentyfive years later (1974), the Rivoli became a showcase for Sensurround. Though “Earthquake” and Sensurround remain indelibly associated with the Chinese Theater in Los Angeles where they premiered, the Rivoli was one among several New York theaters that thrilled audiences with Sensurround effects. These relied on the use of audible and subaudible frequencies that, when played back through large horns, produced vibrating columns of air, identical to the wave form of a real earthquake, which, in turn, actually vibrated the spectator's torso and diaphragm. If the Rivoli was a showcase for sound, it was also, from its origins, identified with visual spectacle. The Rivoli's primary manifestation of spectacle exists on the level of theater architecture. Designed by Thomas Lamb (who also designed the Regent, the Strand, the Rialto and the Capitol), the Rivoli had a facade that resembled the ancient Greek Parthenon; its exterior was "classical": there was a row of fluted Doric columns that supported a terra cotta pediment on which there were more than twenty sculptured figures (including winged horses and centaurs). Reviewers referred to its "snow white Grecian facade and classic columns." The interior decoration was in the style of the Italian Renaissance, with "colors of dull gold, ivory and black, with carpet of gray and seats upholstered in tapestry" (Dramatic Mirror, December 29, 1917). Ben Hall described Lamb's design as "his by-now familiar Adam style, with the arched organ grilles, the dome and the bas-relief sounding board over the orchestra. |

My Dad, Vincent Green, was the Box Office Treasurer for the WARNER Theater

on Broadway beginning with the premier of "Cinerama" (Your article wrongly

identifies the theater as the Broadway Theater) Dad worked the Warner for 17

years. Later he worked with Mike Todd and Dick Pope at the Jones Beach

Marine Theater in Jones Beach, NY The show was "A Night In Venice" The half

time was a presentation of Dick Pope's Aquacade which included water skiing,

diving and a fireworks spectacular. I guess you could say I was a "lucky" kid growing up. I got to meet and know all these famous folks and had the privilege of working in some of the worlds most beautiful theaters. As an aside, Mike Todd, Jr was a dear friend of mine whilst young. He was the inventor/creator of "Scent a Vision" which happened also to be shown at the Warner Theater. Interesting concept but very costly. Thanks for your piece. Alfred H. (Al) Green personally |

Opening |

|

|

|

|

Screen and Sound |

|

The Rivoli. Picture

from trade magazine. The Rivoli. Picture

from trade magazine.Because of the Rivoli's screen size and sound system, it was subsequently used for the presentation of David O. Selznick's “The Portrait of Jennie” (1949). During a climactic storm sequence, a wide angle lens (resembling the Magnascope lens) was used to enlarge the image to 40 by 30-feet and surround sound magnified the sound effects accompanying the storm. As described by New York Times critic Bosley Crowther, in the finale "a green flash of lightening electrifies the screen, which expands to larger proportions and sound vents around the theater roar with the ultimate and savage fury of a green-tinted hurricane." This effort in the direction of stereo sound found dramatic fulfillment in the sound system installed for Todd-AO in the 1950s. As in Cinerama, Todd-AO featured five speakers behind the screen to convey a more convincing illusion of sonic participation than the three behind-the-screen tracks of CinemaScope. In the Rivoli, five Altec "Voice of the Theatre" systems ware situated behind the screen. A sixth surround track was played back on nineteen Altec speakers located throughout the auditorium (fifteen on its side walls and four in the balcony). Each track had its own, 120-watt Ampex amplifier. For “Oklahoma!”, sound was "double system," i.e., the magnetic tracks were on a separate strip of film from the image. This original amplifier was replaced by an Ampex system, consisting of 43 amplifiers, prior to the premiere of "Cleopatra" in 1963. This was done because the original system had a muting circuit (in order to eliminate noise on changeovers). Since “Cleopatra” had musical overlaps during each changeover, these cues were lost on the old system but could be played back properly on the new system. In 1966, William Offenhauser, Jr. described the Rivoli sound system as follows: "There are five Altec horn systems, each containing four low frequency speakers in a double horn module plus four high frequency drivers connected to a 3 X 5 multi-cellular horn. The surround speakers include Altec A-7 horn systems in the balcony and 12-inch extended range reproducers in the ceiling under the balcony" (International Projectionist, November 1966). These vacuum tube amplifiers were finally replaced by a solid state Altec amplifier prior to the premiere of "The Last Valley" in 1971. |

|

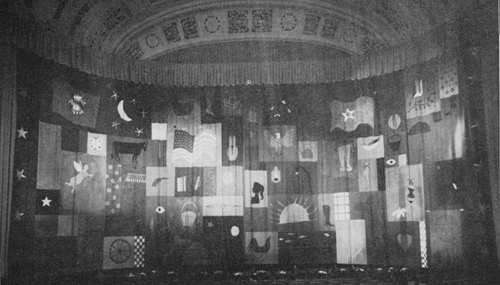

The new curtain for the Rivoli, made by Novelty Scenic Studios, Inc. Original design by Doris Lee. The new curtain for the Rivoli, made by Novelty Scenic Studios, Inc. Original design by Doris Lee.The curved screen was made of a "plastic-coated fabric with an aluminum surface embossed in a formation of lenticules, or tiny lenses, of depth, shape and disposition to prevent the surface from reflecting light back on itself at the extremities and also to adjust light angles for optimum reflection into the audience area" (Motion Picture Daily, October 7, 1955). There were over 600 lenticules or reflectors per square inch of screen surface. The Rivoli's large proscenium became the supportive foundation for an enormous, 52 by 26 foot curved screen. The depth of the screen's curve was 13 feet; the 52-foot width was measured at the cord. The projection aspect ratio was 2.21:1. |

|

Projection |

|

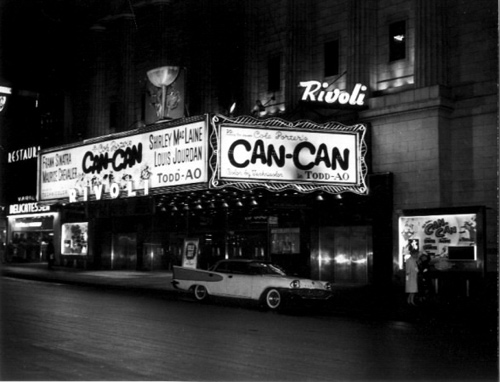

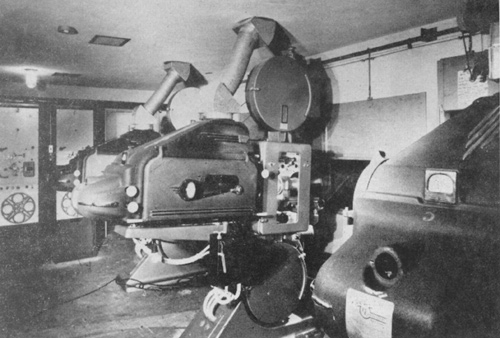

The Rivoli

mezzanine booth with 3 DP70s. Picture from trade magazine. The Rivoli

mezzanine booth with 3 DP70s. Picture from trade magazine.A new projection booth that provided a more direct (i.e., horizontal or head-on) projection angle replaced the original booth, which was located in the "crow's nest" balcony of the theater. The new booth, "built where the first three rows of loges used to be," also had a shorter throw; the distance from the new booth to the screen was only 71 feet. The old booth, which was also outfitted with Todd-AO projectors and was subsequently used to test "corrected" Todd-AO prints, had an extreme projection angle of 22 degrees, which would have introduced "keystone" distortion into the projected image. (In September, just before the opening of "Oklahoma!", "corrected" prints of the film were produced and screened from the Rivoli's old booth. In May 1956, the old booth was used in a comparison test for an audience of SMPTE engineers; first, an uncorrected, then a corrected print was projected; the corrected print successfully eliminated the distortions seen in the uncorrected version. Corrected prints were designed to compensate for extreme projection angles, thus making the format more attractive to older theaters with traditional, balcony booths.) |

|

The Rivoli showing

"Oklahoma!". Picture by Don Whitney The Rivoli showing

"Oklahoma!". Picture by Don Whitney

The new booth was equipped with three Norelco Phillips 70/35mm Universal Projectors. For “Oklahoma!”, the light source consisted of Gretener arc lamps. (According to Bob Throop, Peerless Hycandescent lamphouses were used for “Oklahoma!”; the Greteners were installed for “Around the World in 80 Days”.) Given the larger, 70mm aperture plates, the brighter arc lamsp, the new screen, and the shorter throw, screen illumination was, at 16 foot lamberts, rather brilliant. To secure this additional illumination without buckling, scorching, or burning the film or cracking the projection lens, the projector's picture head was air-cooled, using a system of vents that blew "air cooled to 30 degrees below zero on both sides of the film." After “Oklahoma!”, the Gretener arcs were replaced with Ashcraft carbon arcs. The booth was staffed with two projectionists at all times; the regular Rivoli crew consisted of eight full-time projectionists. When the theater was twinned in 1984, the arc lamps were replaced with xenon and the booth was automated, enabling one projectionist to run both theaters. |

|

"Oklahoma!" |

|

Dr.

Brian O'Brien, H. S. Woodbridge and Brian. O'Brien, Jr. studying the

reviews of ”Oklahoma!”.

(Gentleman far left is unidentified.) Picture from AO News, October 20,

1955. Dr.

Brian O'Brien, H. S. Woodbridge and Brian. O'Brien, Jr. studying the

reviews of ”Oklahoma!”.

(Gentleman far left is unidentified.) Picture from AO News, October 20,

1955.In preparation for the premiere of “Oklahoma!”, the Rivoli underwent an extensive, $350,000 renovation, including the installation of a new booth. The 2000 seats that the theater had at this time were torn out and replaced with over 1600 seats (pre-Oklahoma! seats were 18 inches wide; the new seats were 22 inches wide). Part of the renovation included a new theater curtain which was created especially for the opening of “Oklahoma!”. Measuring 90 X 40 feet, the $12,000 curtain was decorated with "motifs" depicting images associated with the state of Oklahoma. In his review of “Oklahoma!”, critic Bosley Crowther complained about the Todd-AO process. The problems he observed did not apparently arise from projection techniques at the Rivoli (i.e., corrected or uncorrected prints) but from distortions in the optics of certain camera or "taking" lenses. He wrote that "the distortions of the images are striking when the picture is viewed from the seats on the sides of the Rivoli's orchestra or the sides and rear of its balcony. Even from central locations, the concave shape of the screen causes it to appear to be arched upwards or downwards, according to whether one views it from the orchestra or balcony." In his biography of his father, Mike Todd, Jr. reiterated these observations, noting that distortions were introduced by the optics of certain lenses and that American Optical was unable to build an optical printer that could correct those distortions. |

|

The Rivoli

curved Todd-AO screen. Picture from trade magazine. The Rivoli

curved Todd-AO screen. Picture from trade magazine.“Oklahoma!”, which played the Rivoli for 51 weeks, introduced the modern version of "roadshow distribution." This form of distribution featured limited, theatrical-style exhibition, involving advance-sale, reserved seat ticketing and two shows a day (one afternoon and one evening performance; on Saturdays and Sundays there were three shows a day; some newspaper ads indicate that “Oklahoma!” ran at the Rivoli four times a day). Reserved- seat tickets ranged from $1.50 (the balcony) to $3.50 (the orchestra and loge). In a gesture that conveyed the exclusive "theatrical" nature of this roadshow presentation, the sale of popcorn was banned in the theater. This ban was soon adopted by the Roxy, and other, showcase movie palaces. After roughly one year of distribution in this way, a roadshow film would be leased to other theaters "on a restricted showing basis." Thus, at the Rivoli, “Oklahoma!” was followed after a year by Mike Todd's "Around the World in 80 Days" which opened on October 17, 1956 and ran for more than a year. For the premiere and subsequent run of “Around the World in 80 Days”, Mike Todd, Jr. took over as general manager of the Rivoli in an effort to ensure high-quality presentation in the theater. Mike Todd himself "produced" the premiere. Indeed, Rivoli projectionist Jack Rollman was fond of telling the story of Todd senior visiting him in the booth prior to the premiere. After asking some questions, Todd leaned over and put a bill in Rollman's shirt pocket, telling him to "buy yourself some cigarettes." It was a $1000 bill. |

|

Dimension 150 |

|

The Rivoli

with two projection rooms. Upstairs and mezzanine level. Picture from

trade magazine. The Rivoli

with two projection rooms. Upstairs and mezzanine level. Picture from

trade magazine.In 1963, Todd-AO purchased Dimension-150 from inventors Dr. Richard Vetter and Carl W. Williams. Dimension-150 was a 65/70mm wide screen process that, like Todd-AO, achieved a sense of participation by filming scenes with a variety of wide angle lenses ranging from 50 and 70 to 120 and 150 degree angles of view. Projection was on a deeply-curved screen (often as deep as 21 feet) that was approximately 74 by 29 feet (resulting in an aspect ratio of 2.71:1. A few years after this purchase, in 1966, a Dimension-150 screen was installed in the Rivoli prior to the opening of “The Sand Pebbles”, which was filmed in Panavision and was screened at the Rivoli in 70mm. This screen remained in place until the theater was twinned in 1984. (“The Bible” and “Patton”, the only D- 150 films, played elsewhere on Broadway so the Rivoli never ran a D-150 film. However, it projected “Hello, Dolly!”, “Star!”, and “The Last Valley” in D-150.) On October 31, 1984, after a $500,000 outlay for refurbishment, the Rivoli--now the UA Twin--hosted the premiere of Brian De Palma's “Body Double”. |

|

Economy |

|

Where

The Rivoli once was, seen in May 1997. Image by Thomas Hauerslev Where

The Rivoli once was, seen in May 1997. Image by Thomas HauerslevThe Rivoli was not always as successful as other movie palaces. Unlike other palaces, when it was built it was an "independent" and had no affiliation with any studio. As a result, it often had to compete for product. In the Spring of 1919, however, it became part of the Paramount chain. A relatively small movie palace, it originally had ca. 2200 seats. In the late-1920s, its average weekly receipts were ca. $20-25,000. Larger theaters, such as the Capitol (5300 seats), averaged $50,000 while the Roxy (6200 seats) averaged $100,000. During the 1930s and 1940s, it frequently went dark for a month in the Summer. After becoming a United Artists theater in the late 1930s, it occasionally shut down for lack of product. In 1941, it closed for the entire Summer (May through August). During the mid-1970s, the problem of product shortage forced temporary shutdowns of the Rivoli and other Broadway houses, including the Loews Cine, Loews Astor Plaza, Loews State II, the Ziegfeld, and the Criterion. This lack of product, coupled with the theater's large overhead, led to its decline. Part of the Rivoli's problem was that even its most successful films did not always return a profit. For example, “Cleopatra” played the Rivoli for 64 weeks. But in order to get the film, the Rivoli had to put up a cash advance of $1.25 million. During the run, the Rivoli actually filed a suit against the film's distributor, Twentieth Century-Fox because the film did not perform as well as Fox's advance publicity had promised. |

|

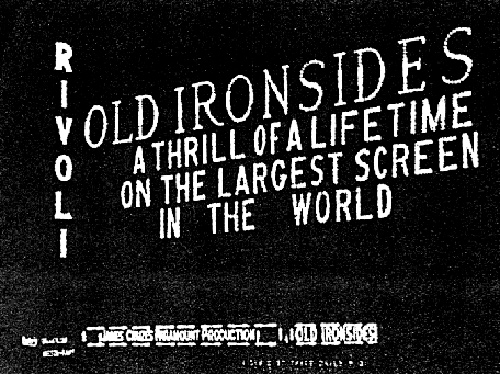

The Rivoli closed in 1986. By this time, the figures on its classical pediment had been removed and its doric columns had been cemented over. It was rumored that its owners, UA Communications, Inc., had altered its facade so that the city could not declare it a landmark (Variety, March 30, 1988). The building was razed in the Fall of 1987. The Rivoli closed in 1986. By this time, the figures on its classical pediment had been removed and its doric columns had been cemented over. It was rumored that its owners, UA Communications, Inc., had altered its facade so that the city could not declare it a landmark (Variety, March 30, 1988). The building was razed in the Fall of 1987.Films shown at the Rivoli include “A Modern Musketeer”, “Affairs of Anatol”, “Wolves of the Rail”, “Deception”, “Chang”, “The Covered Wagon”, “Old Ironsides”, “Zaza”, “Blonde Venus”, “Love Me Tonight”, “Bitter Sweet”, “The House of Rothschild”, “The Wedding Night”, “The Hit Parade”, “Slave Ship”, “You Can't Have Everything”, “Dead End”, “The Grapes of Wrath”, “Wuthering Heights”, “Jamaica Inn”, “London After Dark”, “Flame of New Orleans”, “To Be or Not to Be”, “Cluny Brown”, “Moon and Sixpence”, “Captain from Castile”, “Portrait of Jenny”, “Rear Window”, “Bad Day at Black Rock”, “Oklahoma!”, “Around the World in 80 Days”, “South Pacific”, “Can-Can”, “Cleopatra”, “West Side Story”, “The Sound of Music”, “Deep Throat”, “The Sting” and “Body Double”. I want to thank the following for their help in supplying information for this article: Bob Endres, Joseph Kelly, Richard Koszarski, William Paul, Paul Rayton, Bob Throop, and Dr. Richard Vetter. |

|

|

Go: back

- top - back issues Updated 22-01-25 |

Revolutionary changes in motion picture technology achieve their greatest impact as revolutionary changes in exhibition technology. New formats transform what is seen and heard but do so for

someone - for audiences - in some place - in theaters. In other words, they register their effect on audiences as exhibition formats. In that sense, our experience of the movies remains grounded in our experiences of specific theaters. Our most vivid memories of technologically important moments in film history are tied to the theaters in which those moments first occurred (or first occurred for us). For many, the experience of Cinerama, for example, was inextricably linked to the theater in which they first saw

it - the Broadway Theatre in New York, the Music Hall in Detroit, the Palace in Chicago, the

Revolutionary changes in motion picture technology achieve their greatest impact as revolutionary changes in exhibition technology. New formats transform what is seen and heard but do so for

someone - for audiences - in some place - in theaters. In other words, they register their effect on audiences as exhibition formats. In that sense, our experience of the movies remains grounded in our experiences of specific theaters. Our most vivid memories of technologically important moments in film history are tied to the theaters in which those moments first occurred (or first occurred for us). For many, the experience of Cinerama, for example, was inextricably linked to the theater in which they first saw

it - the Broadway Theatre in New York, the Music Hall in Detroit, the Palace in Chicago, the

For the opening of the theater, its screen was set in a "Conservatory of Jewels," or a "dome within a dome, each studded with crystal gems." This "Conservatory of Jewels" was modeled on the Tower of Jewels at the Panama Pacific Exposition of 1915-16. The crystal setting was built to "flash with kaleidoscopic effect when the light plays on them from the front and will glow softly in their several colors when another set of lights is brought into play behind them." This light show was all the more spectacular in that, apparently, there was no sense of where the source of the light originated. The "brightest of jewels" was said to be "the Screen."

For the opening of the theater, its screen was set in a "Conservatory of Jewels," or a "dome within a dome, each studded with crystal gems." This "Conservatory of Jewels" was modeled on the Tower of Jewels at the Panama Pacific Exposition of 1915-16. The crystal setting was built to "flash with kaleidoscopic effect when the light plays on them from the front and will glow softly in their several colors when another set of lights is brought into play behind them." This light show was all the more spectacular in that, apparently, there was no sense of where the source of the light originated. The "brightest of jewels" was said to be "the Screen."