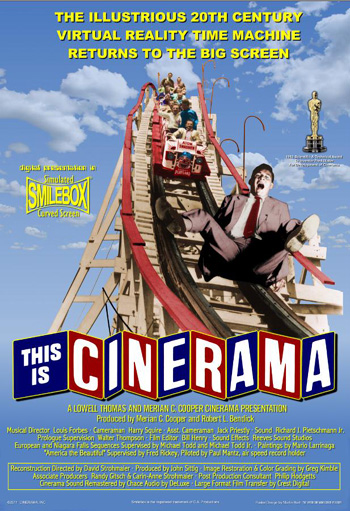

"THIS IS CINERAMA!"

|

Read more

at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: Greg Kimble. This article was written during the summer of 2002. The text was cut down and appeared in American Cinematographer, September 2002. Here it is again, in the full text version. | Date:

06.10.2002 Updated 29.12.2021 |

"THIS

IS CINERAMA!" - These three words changed movies forever, just as Al Jolsen's ad libbed,

"You ain't heard nothing yet" had done in

1927. "THIS

IS CINERAMA!" - These three words changed movies forever, just as Al Jolsen's ad libbed,

"You ain't heard nothing yet" had done in

1927.It was September 30, 1952 at the Broadway Theatre in Manhattan where a world-famous adventurer, a media pioneer, and a first-time producer sat nervously with a quietly confident inventor as the curtain rose on an entirely new medium that would revolutionize motion picture production and exhibition - just when the industry needed it most. As the astonished first night audience tore the theater apart with cheers, the inventor sat quietly, the slightest of smiles on his lips. "What are you, a man or a fish?" asked an aghast friend. "How can you just sit there?" "Oh," the inventor gently replied, "I knew 16 years ago it would be like this." |

Further

in 70mm reading: PDF: Cinema Technology Ladies and Gentlemen, This is Cinerama! in70mm.com's Cinerama page Remastering the CINERAMA Library Louis de Rochemont's "Windjammer" produced in Cinemiracle Cinerama Films How the West Was Won in Cinerama |

Actual

3-strip frame composite from "This is Cinerama". Actual

3-strip frame composite from "This is Cinerama".Fred Waller had indeed labored that long on his dream of a motion picture experience that would recreate the full range of human vision. It used three cameras and three projectors on a curved screen 146° deep. Making an anagram of the letters in "American," he called it "Cinerama". Even in an industry up to its Mitchell magazines in hyperbole, its impact was staggering. Running only 13 weeks in one theater in New York, "This Is Cinerama" was the highest grossing film of 1952. Several more travelogues would follow, climaxed by two dramatic films co-produced with MGM in 1962. Cinerama, which had been rejected by all the majors as too expensive - however impressive it was - now created a landrush. When they saw its drawing power, every studio scrambled to come up with a copycat process. The 1.33 aspect ratio was dead and the widescreen era was on. Cinerama's 3-panel glory days lasted only 11 years, but it has never been forgotten by anyone who saw it. Completely lost for 40 years, now on its 50th anniversary, Cinerama is making a comeback. But the roots of this astonishing system begin much earlier than Waller's experiments in the '30's… |

|

Backstory |

|

Projectionists

Duncan and Tony seen through the Cinerama screen louvres at the Pictureville

Cinerama Theatre. Picture: Thomas Hauerslev Projectionists

Duncan and Tony seen through the Cinerama screen louvres at the Pictureville

Cinerama Theatre. Picture: Thomas HauerslevIn 1787, English artist Robert Barker was awarded a patent for developing the perspective techniques to give a continuous painting the appearance of all-around vision. His creation was the Cyclorama, a 360° painting, first displayed in a purpose-built cylindrical building in London's Leicester Square in 1793. To view London From the Roof of the Albion Mills, you stood on a platform built to resemble a rooftop, with the painting all around you, just as if you were standing atop the actual mills, just blocks away. It was sensationally popular, and cycloramas became a major attraction in all the large cities. You may still view one today in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania at the battlefield museum there. It wasn't long before photographers were creating a truncated version of the cyclorama. Panoramic photography used three or more exposures to cover a viewing angle that a single lens could not encompass. Perfectly suited to landscape photography, the technique was often used to document Civil War battlefields at the end of fighting. While Disneyland's "Circle Vision" is the direct descendant of the cyclorama, it was not the first use of the motion picture camera in this way. Surprising, the 1900 Paris Exposition featured a 10-projector simulated balloon ride. Patrons stood on top of a projection room dressed like a giant balloon basket, under a huge prop balloon. The images were projected on a full 360° screen around them. Closed after only a few days as a fire hazard (the booth was unvented) the exhibit had a prescient name - Cineorama. |

|

70mm

frame from "Napoleon". 70mm

frame from "Napoleon".The first use of a 3-projector panorama in a motion picture was in 1927 (curiously, the same year the anamorphic lens was invented). French director Abel Gance felt that the climax to his 5-hour "Napoleon" needed a big finish, so he shot the final scenes with three cameras mounted over-and-under, and was pleased to see that his "Polyvision" really worked. No one would attempt it again for 25 years. Fred Waller was head of the effects, and later, short subjects departments at the Astoria, NY studios of Paramount Pictures during the 1920's & 30's. When he noticed that pictures photographed with very wide angle lenses had a slight impression of depth, he embarked upon a quest to reproduce, as nearly as possible, the full range of human vision. He succeeded - spectacularly. |

|

Fred Waller |

|

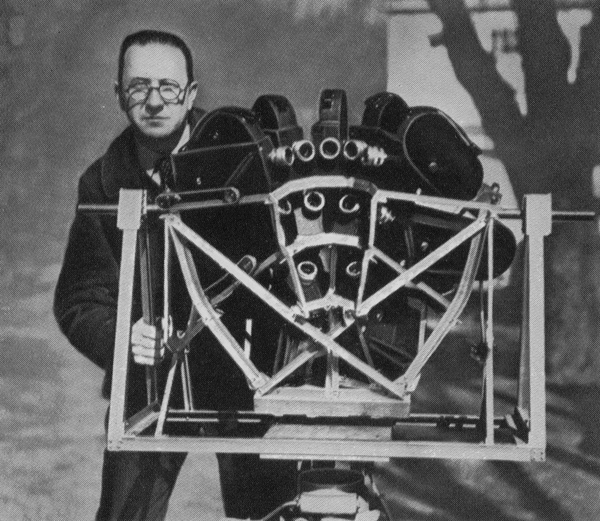

Fred

Waller with Vitarama camera rig. Fred

Waller with Vitarama camera rig.The man who accomplished this was always something of a prodigy. Born in 1896 in Brooklyn, he was repairing his own bicycle -and his friends' - at the age of 4. His father was the first commercial photographer in New York, and after a bout of teenage pneumonia, Waller left Brooklyn Polytechnic at 14 to join him, no doubt to the relief of his physics teachers who were forever losing arguments with him. While there, he invented many labor saving devices he kept secret, and patented the first automatic printer/timer for still photographs. When a shortage of photo supplies during WWI led to the closing of the business, he opened an art studio for the creation of silent film intertitles, working exclusively for Famous Players Lasky (later Paramount Pictures). In 1924 Fred joined Paramount directly as head of Special Effects at their east coast production facility in Astoria, Queens. While there, he produced a cyclone for D. W. Griffith, a shipwreck for Cecil B. DeMille, turned Cinderella's pumpkin into a coach and four and in 1925 built the studio's first optical printer. He was intrigued when he noticed that just as a telephoto lens will flatten an image onto a plane, a wide angle lens does the opposite - gives a sense of depth - without any cumbersome 3-D apparatus. Thus began an intense study of perception that would last over a decade. Paramount closed Astoria in 1927, but Waller didn't waste the hiatus - he went into the boat business and invented the water ski. Returning to Paramount in 1929 as head of short subject production, he became the favorite director of Duke Ellington, Bessie Smith and other major black talent of the day. His musical shorts were distinguished by their creative camerawork and high production value. |

|

Fred

Waller on water ski with a camera from Paramount Pictures. Fred

Waller on water ski with a camera from Paramount Pictures.All the while, Waller was continuing his study of perception. He recognized that each human eye sees two-thirds of the total viewing angle, but we see in 3-D only where the two eyes overlap - directly ahead. Everything further than a few dozen yards away is a flat plane. Often found walking around the house with toothpicks stuck in the brim of his hat, he conducted experiments that surprisingly revealed that it was peripheral vision - and not straight ahead vision that mattered most in spatial perception. Subjects with this center portion blocked navigated a room full of furniture without incident. Those with their peripheral vision obscured (like a horse wearing blinders) fell about. Only one facet eluded him - a panoramic depiction of reality would require an enormously flat screen, perhaps hundreds of feet wide. Ready at last to turn his studies into a practical motion picture system, he set up shop in the carriage house of boating pal David Rockefeller's Manhattan mansion. His first generation system worked - but was far from "practical". It used 11 (!) 16mm cameras to shoot a combined hemispherical image of 2 over 4 over 5 individual films. Connected by external drive belts which synchronized the cameras, the "11-eyed monster" was used for several test films which revealed that the angle of view was so large that the outside cameras were photographing each other. Waller called the contraption the VITARAMA. About this time, Waller was contacted by some exhibitors at the 1939 New York World's Fair. For Eastman Kodak he provided several multi-panel slide displays for their Hall of Color. But it was his first glimpse of the interior of the theme building that made it all come together. The Perisphere was curved. Imagine Waller clapping his hand to his forehead with the 1939 equivalent of "Duh!" flickering across his mind. Human vision is a curved - not a flat - field. |

|

Vitarama Goes To War

|

|

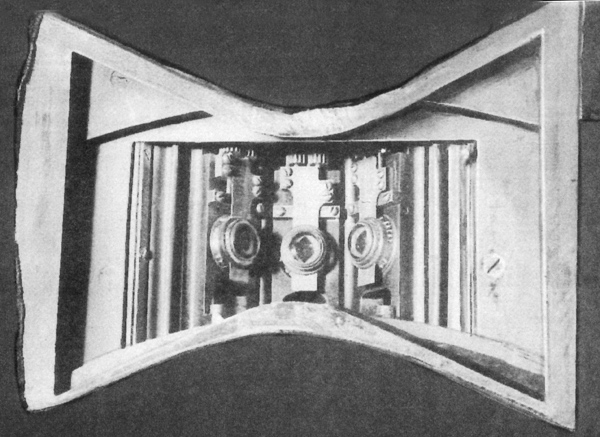

Front

view of The Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer. Front

view of The Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer.When the Vitarama was rejected by fair organizers as "too radical" Fred, disciplined inventor that he was, simply moved on to phase two - five 35mm cameras arranged 2 over 3. With war looming in Europe, Waller adapted his idea to an extremely practical use - an aerial gunnery trainer, which saved fuel, freed up pilots and aircraft for actual combat and eliminated the very real problem of unskilled gunners hitting the aircraft and not the tow target. Since shooting at a slowly towed target didn't begin to mimic actual battle conditions, most gunners never really learned their job until they were in actual combat - and casualties were high. The Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer was the first virtual reality experience - decades before the term was coined. Trainees wore headsets with actual battle and engine sounds, and a sophisticated photoelectric system scored their hits on the photographed planes diving in from out of frame. So realistic and effective was the trainer, that 1 hour was equivalent to 10 of real flying practice. The first group of graduates hit 80% of their combat targets and suffered no losses. At the end of the war, it was calculated that over 350,000 lives were saved by the trainer. Enthusiastic graduates wrote Waller, wanting to see this amazing technology used in a more commercial way. Waller, not surprisingly, was way ahead of them. |

|

The Secret of Oyster Bay |

|

Recording

7-track sound in Oyster Bay, with Cinerama symphony orchestra in front of

curved Cinerama screen. Recording

7-track sound in Oyster Bay, with Cinerama symphony orchestra in front of

curved Cinerama screen. While installing the 75 gunnery trainers contracted by the US Navy and British Admiralty, research and construction was still going on at new facilities in an indoor tennis court out in Oyster Bay, Long Island. Reflections within the sphere had been a real problem on the trainer, so Waller dropped the 2 upper cameras and projected the remaining 3 images - totalling 146° of horizontal angle - onto a curved screen. But the reflections remained, so the screen was rebuilt as 1100 1" vertical strips, all parallel to the viewer. This solved the problem, but made for a costly install. The cameras and projectors were also custom made, as the new system used frames 6 perforations high instead of the usual 4, and ran at 26 frames per second instead of 24. Total exposed negative area was 6 times that of a standard academy aperture. The camera, while not the monstrosity the 11-header had been, was still a behemoth. Unblimped, it weighed over 200 pounds and made an awful racket. With its lead-lined blimp, it tipped the scales at 800 lbs. The lenses, custom made by Kodak for Waller, were the size of a contact lens, with a focal length of 27mm - the same as the human eye. |

|

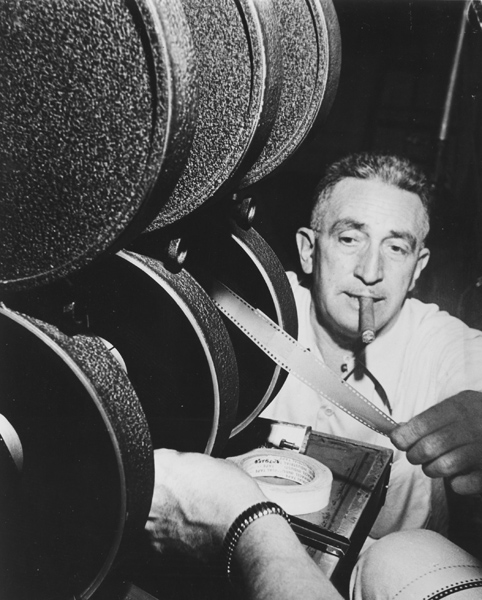

Director

of Photography Harry E. Squire threading the 3-strip Cinerama camera. Director

of Photography Harry E. Squire threading the 3-strip Cinerama camera.This huge expanse of screen real estate could hardly be complemented by a standard monophonic sound track, so Waller brought in sound engineer Hazard Reeves who developed a 7-channel discreet surround sound system. To accomplish this, Reeves invented fullcoat magnetic film - the first use of magnetic media in an optical sound industry. He proved invaluable in another way. When the Rockefellers and Time pulled their funding, Reeves kept the company afloat by buying the assets - for $1600. Reeves made one other important decision. He hired Mike Todd, a Broadway showman who had yet to produce a feature film, as his Cinerama producer, reasoning that his boundless enthusiasm and sales ability was a necessary asset to the new company. Todd also had a relationship with Rodgers and Hammerstein, and promised to bring their hit musical Oklahoma! to the new company to be filmed in Cinerama. One by one, heads of all the majors trouped out to Oyster Bay to see "Waller's Wonder." The 15 minute film included the roller coaster at Rockaway Playland and the Long Island Choral Society singing the Messiah, which had been recorded in the church, then photographed to playback on a set constructed at the tennis court. Both were in black and white. There were also traveling shots of fall foliage and scenes aboard the Rockefeller yacht, which marked the first use of the new Kodak monopack color negative film. Impressed as they were (instinctively turning around as the choir came in on the rear surrounds) they nonetheless knew that exhibitors would never endure the huge conversion costs, and correctly saw how impractical and expensive it would be for regular production. Compliments all around for Fred - and no callbacks. Waller realized that if Cinerama was to succeed, it would be without the help - and financing - of the established picture industry. Fortunately, Waller's Wonder had some very important friends. |

|

Cue Lowell Thomas |

|

Lowell

Thomas filming "This is Cinerama". Note the big Cinerama camera #1 in the

sound proofed box. Lowell

Thomas filming "This is Cinerama". Note the big Cinerama camera #1 in the

sound proofed box.It may be difficult to imagine now, with so many talking heads clamouring for our attention, but once the voice of Lowell Thomas was the single most famous in the world. He was the country's second news commentator. His radio and television career lasted 28 years including his long service as the voice of Fox Movietone Newsreels. A constant traveller with an insatiable curiosity to see new places and people, he was raised in the gold fields of Colorado where his father was a surgeon. The endless parade of prospectors, saloons and cathouses sowed the seeds of his love of the colorful. He would become famous for his egalitarian courtesy, and counted among his friends everyone from the Dalai Lama to the doorman of his Manhattan apartment building. One of his most important friendships was with T. E. Lawrence, the Englishman who fought so hard for Arab independence during WWI. Thomas discovered him by chance while on a trip to Egypt and recognized instantly a great story. He single-handedly built Lawrence into one of the 20th century's great icons with his book and lecture series. Without Lowell Thomas, Lawrence of Arabia would have been but a footnote in history. Lowell Thomas knew both Hazard Reeves and Fred Waller and had produced a Broadway show with Mike Todd. There are various versions of which got the other to join Cinerama. Upon seeing the Cinerama demo for the first time, Thomas knew that this could provide him a success even bigger than Lawrence had been. |

|

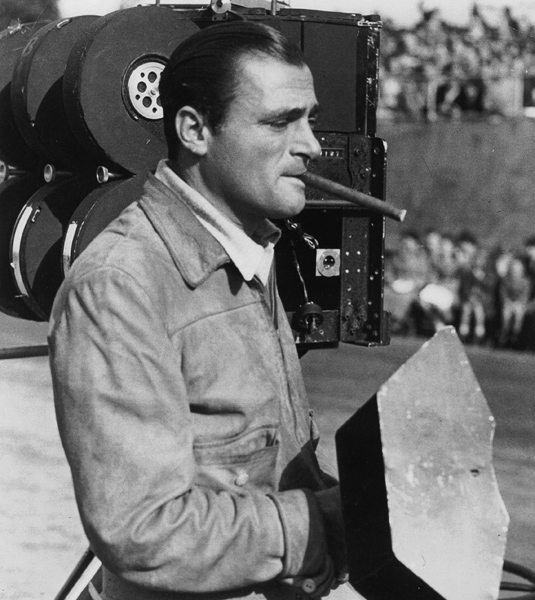

Michael

Todd in Scotland photographing a sequence with the Cinerama camera. Michael

Todd in Scotland photographing a sequence with the Cinerama camera.Todd, dissatisfied with the 16mm he'd used at a recent show at Madison Square Garden, called it "the greatest thing I've ever seen. We must get control of it," and came onboard as producer. When the Lowell Thomas prestige attracted new financing, Mike Todd had his son reshoot the roller coaster in color, then took off for Europe with a small crew. Todd had charmed the IA (the parent organization of movie craft unions) into granting "experimental" status to the project, freeing it from all union requirements. Possessed of what can most tactfully be called a bravura personality, Todd bullied and charmed his way across Europe. Ever the showman with an eye for the spectacular, he photographed the Edinburgh Military Tattoo, a Venice canal boat parade, a Spanish bullfight (but thankfully not the final coup de grâce) and the Act II finale of Aida at La Scala, the first time cameras had every been allowed inside the venerable opera house in Milan. A few phone calls in Vienna turned up enough of the famous Boy's Choir to sing The Blue Danube Waltz for the huge camera. The footage, sent to NY for processing and so unseen by the crew, created a sensation back at corporate headquarters. But the board of directors was not happy with Todd's assumption that he knew best in all matters and it was becoming hard to attract more financing because, as Lowell Thomas candidly writes, "Wall Street hated Mike Todd." So he was quietly bought out and left the company, happily taking his money and developing Todd-AO, the 30 fps 70mm system with the huge bug-eye lens, which was designed to be, as he had stipulated, "Cinerama out of one hole." His first production? "Oklahoma!". This left the board with just over an hour of great footage - but no movie. Cinerama needed another friend. Quickly. |

|

Enter The Veteran |

|

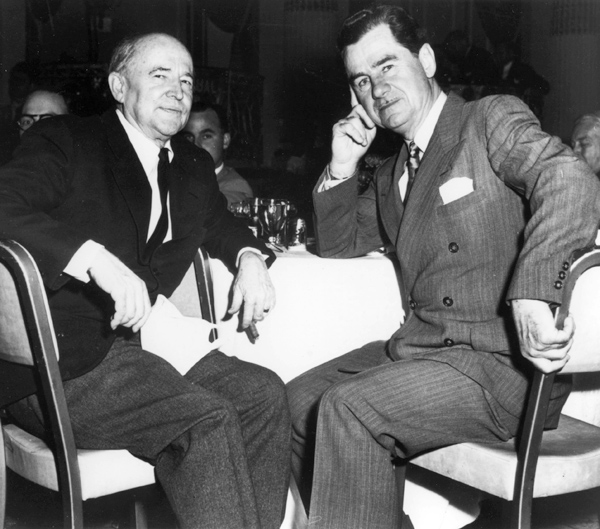

Merion

C. Cooper and Lowell Thomas Merion

C. Cooper and Lowell ThomasIn a business know for its larger-than-life personalities, few stand taller than Merion C. Cooper. A life-long adventurer in the 19th century fashion, he resigned from the Naval Academy in his senior year, and shipped out as an able seaman intending to get to Britain and join the Air Corps during WWI. Passport problems sent him back to the States where he joined the Georgia National Guard and chased Pancho Villa across Mexico. He finally got his chance to fly when the US entered the war, but in 1918 he was shot down behind enemy lines and spent the rest of the war in a prison camp, where his severe facial burns were excellently repaired by German plastic surgeons. The next year he joined the Polish Army to help them resist the Russian invasion, but was again shot down. He escaped his Soviet prison after 10 months, and 26 days later, with the aid of a professional smuggler, made it to the Latvian border. After a short stint as a reporter for the NY Times, he and cameraman buddy Ernest Schoedsack hit upon an idea to combine their two loves - flying and exploration. They headed for the Persian Gulf and spent the next several months with one of the wandering tribes there as they sought pasture during the terrible equatorial summers of the Middle East. The result was "Grass" (1925), a landmark in documentary film. Two years later, they released "Chang", shot in Siam, to even greater success. Brought to RKO by David O. Selznick to help with production, Cooper saw some dimensional animation tests by effects man Willis O'Brien for the studio's unmade "Creation". Cooper had no interest in the project, but was very interested in O'Brien, who's magic with animated model animals he saw as the answer to a major production problem on a giant ape picture he wanted to make. Selznick left for MGM in 1933, and Cooper was appointed Head Of Production at RKO. His jungle adventure picture had taken a year to complete and cost an astronomical $650,000. But when released, "King Kong" was just as astronomical a success. It played continuously at New York's Radio City Music Hall and the Roxy for over a year. Eventually, Kong would take its place as one of the greatest fantasy adventure films ever made - perhaps the greatest. Cooper was instrumental in the early success of 3-strip Technicolor, and in 1941 re-enlisted in the Air Force where he was Chief of Staff for the famous "Flying Tigers" which flew against the Japanese - over the Himalayas. After the war, he returned to producing, and with his partner John Ford, made several pictures, including "She Wore A Yellow Ribbon" and "The Quiet Man". |

|

Front

view of the Cinerama camera. Note three contact-lens sized lenses. Front

view of the Cinerama camera. Note three contact-lens sized lenses.Without Mike Todd, Lowell Thomas knew Cinerama needed a new producer, and he called Cooper, who agreed to take over production, direct new material and personally edit it all into a releasable film. The board liked the idea of shooting in Cypress Gardens (where the Waller-invented water ski would be featured) but hated his plan for a 26-minute flight across the country. And, oh yes, would he please put the roller coaster at the end of the film? But the board was no match for the man who had faced enemy fire, imprisonment and charging elephants. Cooper got his way, and the picture was finished - barely in time.

The lights dimmed on the invitation-only black tie audience, and on the

screen, the familiar face of Lowell Thomas droned on for 15 minutes about

the history of photography - from a regular 1.33 frame, and in black in

white. Patrons began to wonder if they'd been had. "Cinerama, so

what's the big deal?" Suddenly, the curtains parted - it seemed they

would never stop - until a deeply curved screen nearly 40' high and over

90' wide was filled with the Rockaway roller coaster, introduced by

Thomas' simple, triumphant, "Ladies and gentlemen, THIS IS

CINERAMA!" |

|

The Big(ger) Picture |

|

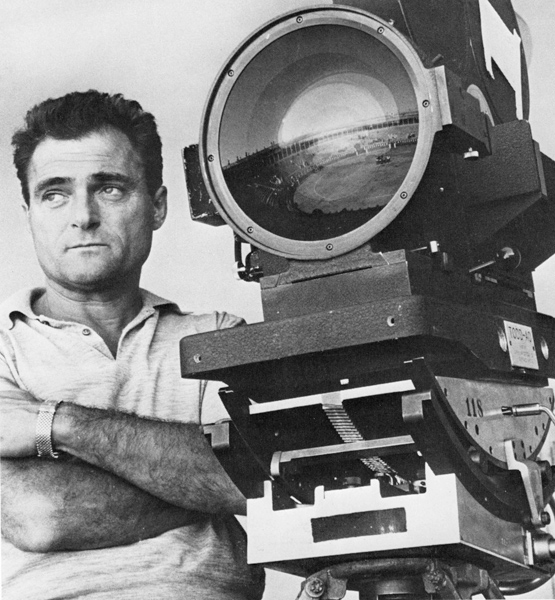

Michael

Todd and the big 128 degree Todd-AO lens. Spanish bull ring is reflected

in lens. Michael

Todd and the big 128 degree Todd-AO lens. Spanish bull ring is reflected

in lens.Spyros Skouras, head of Fox, dispatched a team to France to track down Prof. Crétien, who's 1927 anamorphic lens was well known around town. Cooper had considered using it on "Chang", and Selznick flirted with the idea for "Gone With The Wind" but decided to go with Technicolor instead. Warners sent out a search party as well - and found the good professor the day after Fox had signed him to an exclusive contract. Although his patents had recently expired, putting his invention in the public domain, the contract secured his expertise for Fox. A year after "TIC", "The Robe" would be the first film in CinemaScope - advertised as "The Modern Miracle You See Without Glasses" to distance it from the 3-D craze. Advertising artwork for the new process was strikingly similar to that for Cinerama. Across town at Paramount, the camera department went into overdrive to come up with a viable widescreen system and created VistaVision, which used 35mm film run sideways, each frame being twice as big as normal (8 perfs). Release prints in any aspect ratio could be made from the 1.5 aspect ratio negative. The larger negative area was especially important in the early days of monopack color film which was very slow and grainy. Technicolor, seeing the end of 3-strip photography coming, retooled their cameras for 8-perf shooting, added a 1.5 squeeze anamorphic lens and called it Technirama. And of course there was Mike Todd, who's 70mm Todd-AO was the closest copy of Cinerama. All this was for the best. In the five years since the end of WWII, the picture business had seen a loss of 50% of its revenues, due to the combined effects of the Paramount Consent Decree, which had stripped them of their theaters, increased options for leasure time use, and the big meanie - television. Widescreen got people back into theaters - for a while. This, in fact, is Cinerama's greatest legacy. Since it premiered in 1952, widescreen cinema and stereophonic sound have not disappeared from movie screens for a single day. Of course, all of these copycat systems used only one projector, and none were designed to fill your peripheral vision to give you a sense of being in the scene. They were merely wide, and successful as they eventually were, the effect of Cinerama was (and is) completely unique. Because it fills your peripheral vision, your brain interprets what it is seeing as a real experience. Which explains those woozy patrons running out at intermission for Dramamine… |

|

Success - Now What? |

|

"This Is

Cinerama" (referred to as "TIC" by fans) had

cost $512,000 to make - and made over $4 million in its first year. This

success caught everyone off guard. The film had been made just to

demonstrate the process. No real thought had been given to what would come

next. And then there were the corporate politics. "This Is

Cinerama" (referred to as "TIC" by fans) had

cost $512,000 to make - and made over $4 million in its first year. This

success caught everyone off guard. The film had been made just to

demonstrate the process. No real thought had been given to what would come

next. And then there were the corporate politics.The company was split into two separate units - Cinerama Inc. which made the cameras, sound equipment and projectors, and Cinerama Productions which made the films. Cooper was given a 5-year contract as general manager in charge of production. Knowing a good thing when he saw it, Cooper tried to get control of the company but lost out to Stanley Warner Theaters who bought it in a paper transaction to allow Mike Todd to sell his shares, which he hadn't told the IRS he owned. Not being a production entity, Stanley Warner had less than no idea what to do with their new acquisition. Audiences, returning to "TIC" in lieu of any other product, filled out suggestion cards as to what the next Cinerama film should be. It took 3 years, but finally "Cinerama Holiday" hit the screen in 1955. The idea was simple enough - two couples, one American and one Swiss, would swap continents, each followed by a Cinerama camera crew. It is now a priceless time capsule of mid-1950's life. Recovering from their lost momentum, Cinerama Productions began to release a new film each year. 1956 gave us "Seven Wonders of the World", a Lowell Thomas concept which begins at the pyramids - the only surviving wonder of the original seven - and continues around the world to Victoria Falls, St. Peters in Rome, the Suez Canal (where the camera plane was fired upon) and the Taj Mahal. |

|

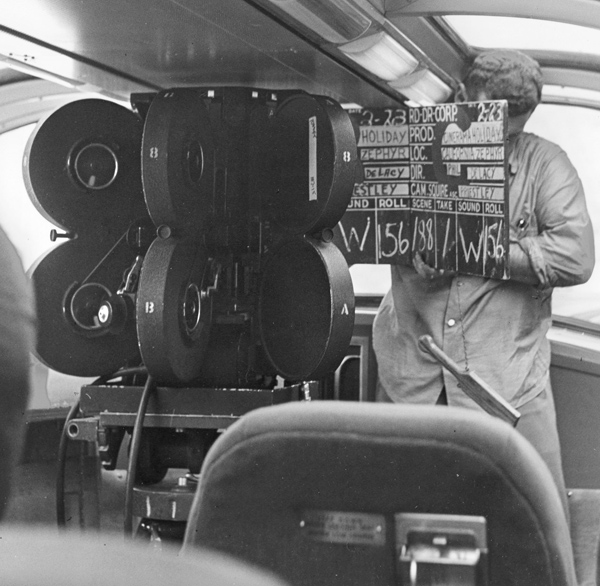

Rear

view of the Cinerama camera photographing "Cinerama Holiday" on

board a Vista Dome train car. Rear

view of the Cinerama camera photographing "Cinerama Holiday" on

board a Vista Dome train car.The idea of exploration infuses the next release, "Search For Paradise" (1957) shot entirely in the rugged mountain ranges of Katmandu, where the crew was the first to run the rapids of the treacherous Indus River, with 5 times the flow of the Colorado at its flood. On the last run, cast member Jim Parker rode along but didn't bother with a life jacket. The raft flipped, and both Jim and the camera were lost. Just days before, he had been heard to remark, "I wish I could spend the rest of my life here." In 1958, what would be the last Cinerama travelogue was released. "South Seas Adventure" took a camera crew throughout the South Pacific on a sailing ship, recording colorful Polynesian life. On Pentecost Island, the production found a tribe who once a year had a day-long ceremony where the men would leap off a one hundred foot tower with vines tied around their legs as a test of manhood. This Cinerama sequence was the first recorded incidence of bungee jumping. Pentecost had been occupied by the Japanese during the war. They never found the tribe, but Cinerama did. 1958 also saw the release of a complementary format film, "Windjammer", which followed the Norwegian tall ship Christian Radich around the world. It was filmed in CineMiracle, which used three Mitchell cameras converted to 6-perf pulldown, and photographed the side panels by reflecting them in mirrors. This handily evaded the Cinerama patents. When "TIC" became the surprise hit of the 1954 Exposition in Damascus, completely eclipsing the Soviet exhibits, the Russians built their own 3-panel system, claiming the US had stolen it from them (of course). KinoPanorama was a huge hit both in the Soviet Union, where 15 films were made, and took prizes at later world fairs. In 1966, a compilation of scenes from these films was released in America as "Cinerama's Russian Adventure". It only played for a short time in Chicago and was unseen elsewhere in the States. |

|

Twilight |

|

Front

view of the Cinerama camera photographing "Cinerama Holiday" on

board a Vista Dome train car.

Director of Photography Harry E.

Squire is seen to the right. Front

view of the Cinerama camera photographing "Cinerama Holiday" on

board a Vista Dome train car.

Director of Photography Harry E.

Squire is seen to the right.The five-year contract with Stanley Warner had expired and Lowell Thomas hoped for a change in management - for the better. For a time, it seemed as though it might happen. The company was acquired by Nicolas Reisini, an import/export tycoon who had been entranced with "Napoleon" and had a real vision for the company. His first idea was a good one - Itinerama. He put Cinerama on trucks, and took it all over Europe to the countryside where there was no theater nearby. A tent was put up, and 3,000 people could view a Cinerama film. And so it was that one memorable night in France, Abel Gance, who had the idea nearly 40 years before, was the guest of honor at a Cinerama screening. Reisini also began an aggressive global building campaign. Over 200 purpose-built theaters were planned, to bring Cinerama to the world. When the Tokyo theater opened, it was such an event that even the Emperor came. Reisini's second idea wasn't bad, either. He made a co-pro deal with MGM for a string of traditional dramatic films. George Pal brought his special touch to "The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm", a bio-pic interspersed with dramatizations of their fairy tales. It featured several visual effects and was moderately successful. But it was the classic "How The West Was Won" which would become the crown jewel of Cinerama, the last 3-panel film, and the highest grossing film of 1962, just as "TIC" had been 10 years before. |

|

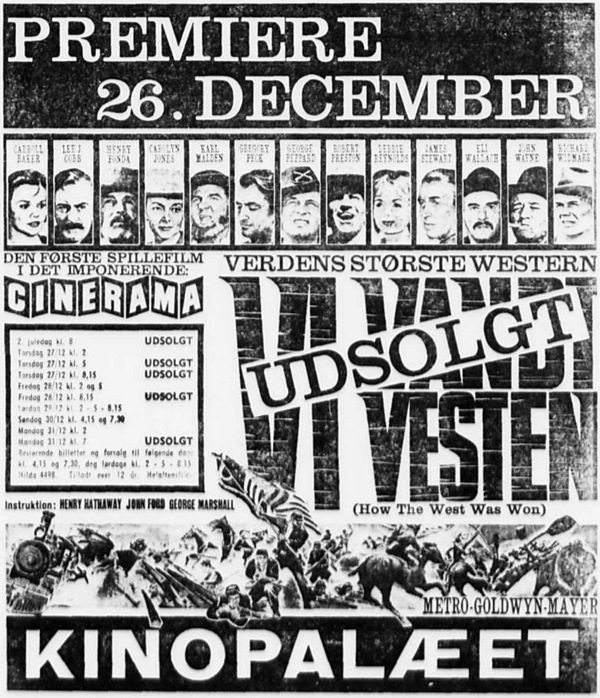

"How

The West Was Won" in Cinerama at the Kinopalæet in Copenhagen,

Denmark. Premiered 26. December 1962 and ran until 3. June 1963. "How

The West Was Won" in Cinerama at the Kinopalæet in Copenhagen,

Denmark. Premiered 26. December 1962 and ran until 3. June 1963."HTWWW" was a multi-generational story which followed the Prescott family as they headed West. Shot entirely on wilderness locations with several units, an all-star cast, and three directors over a two year period, it was a major achievement for director general Henry Hathaway, who studied the Cinerama process in depth and learned how to work around its limitations. Hathaway proved that the process, thought difficult and expensive, could be effective with the right property. It is a taste of what might have followed. If only… Unfortunately, Reisini's vision had expanded faster than his revenues. His 360° consumer camera wasn't selling, nor his home video tape recorder. The company, unfamiliar with studio accounting practices, had taken a bath in "overhead" charges on "HTWWW". When the 70mm comedy "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World" proved a success, he decided the 3-panel process was just too expensive and made all future films in either Technirama or Super Panavision 70, hoping to trade on the established marquee value of the Cinerama name. Of course, audiences weren't fooled by this bastardization of the process - it was impossible not to notice that there was only one projector. Several subsequent films were advertised as being "in Cinerama" among them "Khartoum", "Grand Prix", and "Ice Station Zebra". Originally contracted for 3-panel, "2OO1" was shot in 70mm when effects supervisor Douglas Trumbull saw the long, slender design for the Discovery spacecraft and knew it would kink badly at the blend lines. "The Greatest Story Ever Told" actually began production in 3-panel, but after a few days director George Stevens was talked into using Ultra-Panavision by ill-informed advisors. Now it happens that the original specs for Ultra-Panavision (70mm with a 1.25 squeeze) yield the same aspect ratio as Cinerama (2.76), and 3-panel prints could be made from the negative, although this has never been done. (Imagine the chariot race from "Ben-Hur" projected this way!) |

|

"It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World"

(Produced in Ultra Panavision 70) "in Cinerama" at the Kinopalæet in

Copenhagen, Denmark. Premiered 21. December 1963 and ran until 9. April

1964. "It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World"

(Produced in Ultra Panavision 70) "in Cinerama" at the Kinopalæet in

Copenhagen, Denmark. Premiered 21. December 1963 and ran until 9. April

1964.Worse, Reisini also called a halt to all R&D, which stopped production of Waller's design of a 35mm 16-perf pull-across camera with a curved gate, and curved real element lens. Three-panel prints would be made from the single negative, forever solving the image kinking problem where the panels (each with its own vanishing point) met. Waller had never stopped trying to improve the process, and had always seen 3-panel as first generation technology. He would know none of the fate of his brainchild, however. He passed away in 1954, just days after receiving an Academy award for Cinerama. The Cinerama name rapidly lost its caché and market share. Theaters were un-converted to conventional projection. Of the several purpose-built "Super Cinerama" theaters, only a few remain, and only two, the Seattle Cinerama and the Cinerama Dome in Hollywood, are equipped to show 3-panel films. (The Cooper in Denver, Colorado was recently demolished for a parking lot despite its listing on the National Register of Historic Places.) The company assets and distribution arm were purchased by Pacific Theaters, which mothballed the equipment and sold the remaining prints as sound spacer. The last presentation of 3-panel projection was at a festival in Paris in 1972. As late as 1976, Lowell Thomas was still trying to revive interest in the process for the nation's bicentennial. He firmly believed that someday, someone would help Cinerama achieve its potential. And so it languished, presumed dead, for nearly 20 years. |

|

The Cavalry Arrives |

|

Pictureville

Cinerama in Bradford, England, 1996. Picture: Thomas Hauerslev Pictureville

Cinerama in Bradford, England, 1996. Picture: Thomas HauerslevIn 1983, American Cinematographer Magazine commissioned a 20th anniversary retrospective article on "How The West Was Won". Appearing in the October issue, it celebrated Cinerama and mourned its passing. This caught the eye of retired projectionist John Harvey, who decided he would bring back Cinerama "if I have to do it by myself." He ferreted out three projectors and a sound head and installed a full working Cinerama theater - in his home. At first he only had 4 minutes of footage. Gradually, he cobbled together a print of "TIC" and one of "HTWWW", the latter in IB Technicolor. Eventually he acquired a pristine, but faded Eastman print of "Cinerama Holiday". These he happily shared with the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television in Bradford, England beginning in 1993. For years this was the only place on the planet where Cinerama could still be seen. In 1996, Larry Smith, manager of the small art house cinema, The New Neon in Dayton, Ohio, convinced Harvey to move his equipment there. And so began the renaissance of 'ole 3-eyes. Press attention brought people from all over the world to see the process they thought was lost forever. Not long after, Paul Allen saved the Seattle Cinerama Theater from the wrecking ball, and restored it to its full 3-panel glory, ordering new prints of "TIC" and "HTWWW". Much of the continuing interest in saving Cinerama can be traced to the efforts of Dave Strohmaier, who has spent 5 years researching the process, and collecting memorabilia and interviews with surviving cast and crew for his documentary, "The Cinerama Adventure". A labor-of-love project, it is now being completed with the help of the American Society of Cinematographers and Laser Pacific. |

|

Director

of Cinerama remasters Dave Strohmaier and producer of the Cinerama remasters

Randy Gitsch posing in Nyhavn, Copenhagen in 2015. Picture: Thomas Hauerslev Director

of Cinerama remasters Dave Strohmaier and producer of the Cinerama remasters

Randy Gitsch posing in Nyhavn, Copenhagen in 2015. Picture: Thomas HauerslevThe original film materials for all the travelogues have been vaulted for decades. Fading as we speak, they are awaiting restoration - if only someone will put up the money. And what of the Cinerama Dome in Hollywood? Nearly lost in a planned conversion to flat-screen and buried inside a parking structure, the Dome was saved largely through the efforts of the Los Angeles Conservancy under the direction of Doug Haines' Friends of Cinerama. This is quiet vindication for John Sittig, long time Pacific Theaters manager, who has been quietly lobbying behind the scenes for years to install Cinerama in the Dome. This fall, it will happen at last. Made at the order of Michael Forman, head of Pacific Theaters, a new print of "This Is Cinerama", struck from the original negative by Crest Lab, will be shown on September 30th, the 50th anniversary of the original premier in New York. This will mark the first time 3-panel has ever been shown in the Dome. In October, a 40th anniversary re-premier of "How The West Was Won" is planned. This will be welcome news for millions of baby boomers for whom Cinerama is a cherished childhood memory of an utterly unique experience they've been denied for over 40 years. Come September, they'll all feel a bit like Lillith Prescott toward the end of "HTWWW", when she is joyfully re-united with her family after decades of separation.

|

National

Museum of Photography, Film and Television Dayton article #1 and #2

|

Three strip CINERAMA film samples |

|

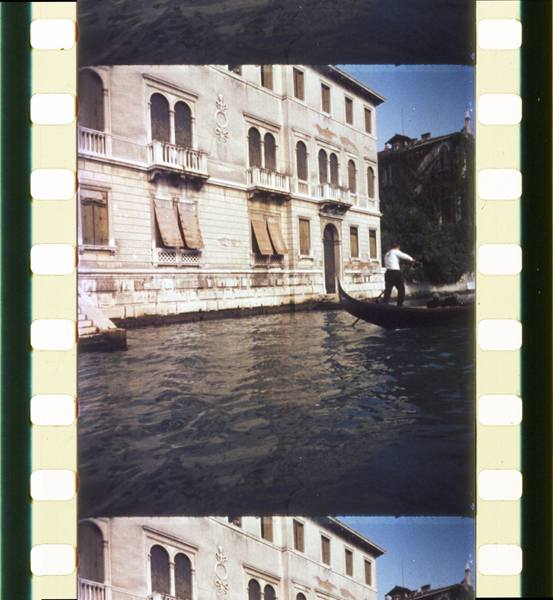

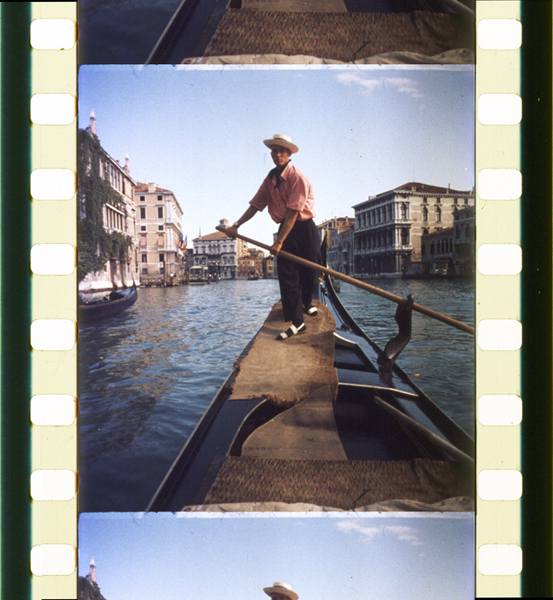

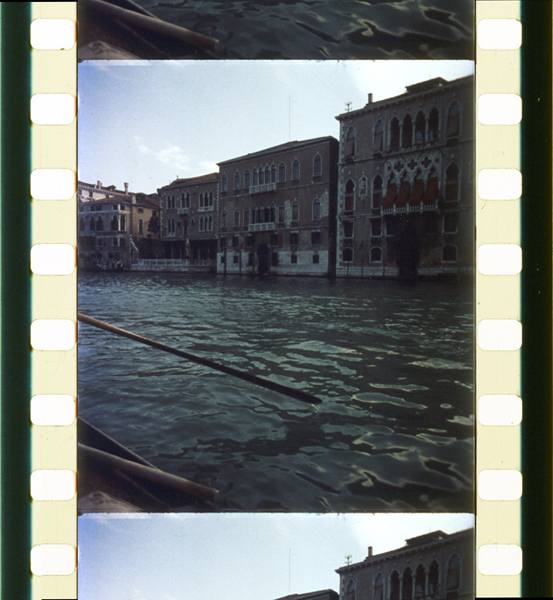

Actual

3-strip frame from "This is Cinerama". Actual

3-strip frame from "This is Cinerama". |

|

Actual

3-strip frame from "This is Cinerama". Actual

3-strip frame from "This is Cinerama". |

|

Actual

3-strip frame from "This is Cinerama". Actual

3-strip frame from "This is Cinerama". |

|

Actual

3-strip frame composite from "This is Cinerama". Actual

3-strip frame composite from "This is Cinerama". |

|

Actual

3-strip frame composite from "This is Cinerama". Actual

3-strip frame composite from "This is Cinerama". |

|

Actual

3-strip frame composite from "This is Cinerama". Actual

3-strip frame composite from "This is Cinerama". |

|

Actual

3-strip frame composite from "Cinerama Holiday". Actual

3-strip frame composite from "Cinerama Holiday". |

|

Actual

3-strip frame composite from "Cinerama Holiday". Actual

3-strip frame composite from "Cinerama Holiday". |

|

Actual

3-strip frame composite from "Seven Wonders of the World". Actual

3-strip frame composite from "Seven Wonders of the World". |

|

Actual

3-strip frame composite from "Search for Paradise". Actual

3-strip frame composite from "Search for Paradise". |

|

Actual

3-strip frame composite from "Search for Paradise". Actual

3-strip frame composite from "Search for Paradise". |

|

| Go: back

- top - back

issues Updated 22-01-25 |

|