Journey To The Stars | Read more at in70mm.com The 70mm Newsletter |

| Written by: DARRIN SCOT, American Cinematographer. June, 1963 | Date: 26.10.2010 |

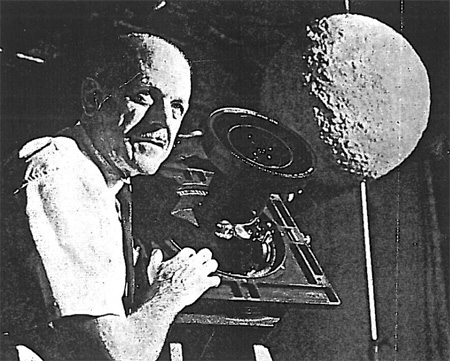

SPECIAL CINERAMA CAMERA, shown

above, equipped with 0.9-inch, f/2.2 inverted telephoto lens and using

70mm film was employed in photographing "Journey To The Stars," much of

it in single-frame exposures. SPECIAL CINERAMA CAMERA, shown

above, equipped with 0.9-inch, f/2.2 inverted telephoto lens and using

70mm film was employed in photographing "Journey To The Stars," much of

it in single-frame exposures.Space-age movie in hemispherical format required novel wide-angle photography and vertical projection on dome-shaped screen. When THE SEATTLE WORLD FAIR opened last summer the "hit of the show" was the Spacearium featuring a new space motion picture system created and constructed by Cinerama for the Boeing Co. and the United States Science Exhibit. Inside the U.S. Pavilion a 15-minute color film, "Journey to the Stars", was projected on a hemispherical 360-degree, 75-foot screen, filling the 6,000 square foot surface with all the excitement of an actual trip to the outer galaxies. During the run of the Fair, standing audiences of 1,000 at a time viewed the spectacle. It played more than 6,000 performances before an audience totalling 4½ million people and springboarded the formation of a vital new company serving the motion picture and missiles industries, the Cinerama Camera Corporation. The story behind the development of the Spacearium filming and projecting systems is one of remarkable technical achievement. The challenging assignment called for a totally new concept of motion picture presentation—including the design and construction of photographic equipment, optics, special processing, printing and film-handling equipment, projection, a giant dome-shaped screen, a film production involving intricate three-dimensional animation and a precisely engineered auditorium in which to screen it—all to be completed in less than fourteen months. | More in 70mm reading: World's Fair Cinerama facility in Seattle in70mm.com's Cinerama page Cinerama 360 |

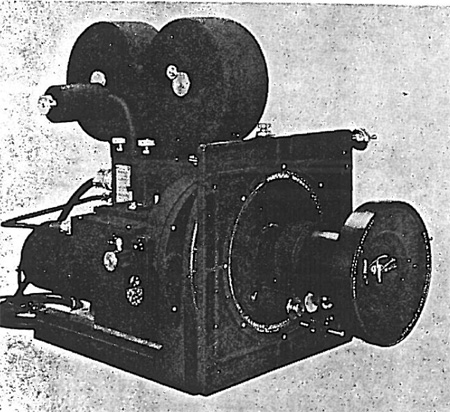

CINERAMA CAMERA CORPORATION'S

super-wide angle 70mm camera with "bug-eye" lens features frame counters,

forward and reverse operation, single frame photography, dissolving

mechanism and special shuttering affording long exposure times per

frame. CINERAMA CAMERA CORPORATION'S

super-wide angle 70mm camera with "bug-eye" lens features frame counters,

forward and reverse operation, single frame photography, dissolving

mechanism and special shuttering affording long exposure times per

frame.Cinerama, Inc., was designated prime contractor to work with a group of sub-contractors including Fine Arts Productions (film production), Fairchild-Curtis (optics), Benson-Lehner Corporation (photographic and projection equipment), Film Effects of Hollywood (printing equipment, optical effects and release printing), Technicolor, Inc. (processing) and many others. Program Manager and Coordinator of the project, William D. Lüttschwager, realized that the challenge was far different from that of normal motion picture production and that the first logical step was one of experimentation with standard and available equipment to prove the feasibility of the system. For this he borrowed from Naval Training Devices an inverted telephoto lens having a 142-degree field and originally designed for use in Naval Gunnery Training. With this lens, a Bell & Howell camera and a 35mm projector, Fine Arts Productions began shooting tests and experimenting with projection onto a 20-foot dome. Concurrently, Benson-Lehner began developing the 70mm production camera, adapting it from a 2¼" x 2¼" frame-size model originally designed for photoinstrumentation work. This camera had to be modified for animation photography and fitted with optics yet to be engineered. The camera utilized ASA Type 1 perforated film, having a .234 pitch. The mechanism was modified to permit stop-motion photography and included such refinements as frame counters, forward and reverse operation, thru-the-lens viewing, critical focus adjustment, a dissolving mechanism and special shuttering devices for exceptionally long exposures. A method was also devised to mount the camera on an animation crane so that it could be rotated in increments of 1/10 degree in any direction. Curtis Optical, assigned the task of designing the lenses, delivered the first one—a 0.9-inch focal length, f/2.2 inverted telephoto—which could be used for both photography and projection. Its resolving characteristics were of a very high order —500-600 lines per millimetre visually on axis and 70-80 on film, with virtually no vignetting at the edges. Its angular field of slightly more than 162 degrees assured sharp projection coverage of the vast hemispherical dome. |

|

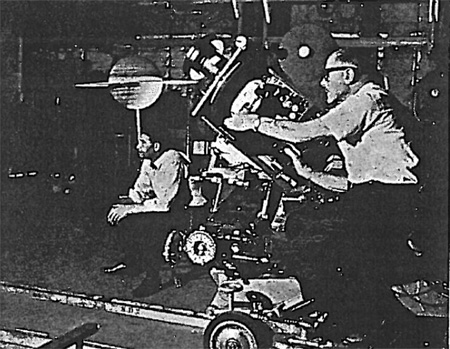

LINING

UP a dolly shot. Camera door is open, permitting adjustment of mechanism

and focusing. Saturn-type satellite model in background is one of

several miniatures constructed for the production and shot against black

backdrop. LINING

UP a dolly shot. Camera door is open, permitting adjustment of mechanism

and focusing. Saturn-type satellite model in background is one of

several miniatures constructed for the production and shot against black

backdrop.Because the ASA Type 1 film perforation is non-standard it was necessary to place special orders with Eastman Kodak Company for the 70mm film stocks required—making the first time that Eastman Color negative, internegative and print stocks were manufactured in this size and perforation. In addition, three different black-and-white negatives were supplied: Tri-X, Plus-X and Background X. Meanwhile, Fine Arts Productions, Inc., under the guidance of Producer-director John Wilson and Chief Cameraman Eugene Borghi, had begun filming the simulated voyage into 60 thousand billion miles of inter-galactic space. The production called for incredible precision and the exploration of new frontiers in three-dimension stop-motion photography and animation. The primary problem was the vast scope of the format itself: a film to completely encircle the audience— which would be projected on the world's largest motion picture screen, an 8,000 square foot aluminum dome weighing eight tons and dwarfing the 3,000 square foot screens used for the triple-projector showings of Cinerama. The film was to encompass a vertical angle of 160 degrees, only slightly less than that of the natural horizon. Previously the widest vertical angle covered by a projected motion picture had been 140 degrees, achieved by a device used to train flyers during World War II. To simulate the black sky ablaze with stars that was to serve as the background for the entire film, a special 10-foot dome was constructed of fiberglass painted black on the inside and drilled with more than 1,000 individual holes accurately plotted to duplicate constellations covering 210 degrees of the Northern hemisphere. The holes, representing five magnitudes of star brightness, ranged in size from 1/8 to 1/64 inch in diameter. Outside and above the dome forty 10KW lamps produced an overall even light that was given a measure of diffusion by a white silk parachute draped over the dome. The effect was to soften the light coming through the holes without eliminating the required star-like sparkle. The camera was placed inside the dome, shooting straight up at the man-made heavens. Because of the need to minimize grain and insure maximum sharpness of the star images, this background scene was photographed on black-and-white Plus X film and printed on Eastman high contrast stock. | |

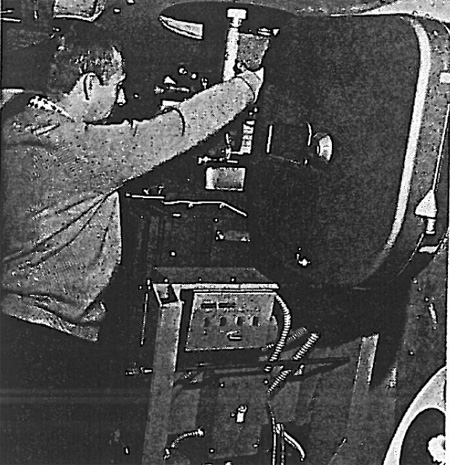

FILM IMAGE IS projected

vertically on overhead screen by this special Cinerama projector to

produce a full 360-degree hemispherical picture of star-studded heavens.

Here, operator makes focus adjustment before starting run of film. FILM IMAGE IS projected

vertically on overhead screen by this special Cinerama projector to

produce a full 360-degree hemispherical picture of star-studded heavens.

Here, operator makes focus adjustment before starting run of film.For part of the footage, large stars and galaxies such as the Milky Way were accurately reproduced in white paint on the inside surface of the dome. These paintings were illuminated by leak-light spilling through fiberglass shields arranged around the bottom of the dome. Thus, the small stars were exposed by light reflected from the painted inner surface. By experimenting, exposure was balanced to photograph both in proper tonal ratio without graying the background. Three-dimensional models of the planets, asteroids and the Moon were constructed in miniature and averaged three feet in diameter. Colors and topography were accurately reproduced according to latest scientific data. (It required two months of steady work to faithfully duplicate the crater-pocked surface of the moon). These models were lined up in proper relationship against a black-draped stage on a 100-foot path along which the stop-motion camera dollied in steps of 1/4-inch per frame. Crews rotated each model by means of intricate gear-mechanisms as the director called out numbered directions for each exposure. The huge inverted telephoto lens, with its 30 lbs of glass elements, violated many of the established principles of optics and, in effect, made its own rules. Firstly, spherical aberration caused a fall-off of sharpness at the edges when the image was in sharp focus at the center of the composition, and vice versa. Through trial-and-error experiments, a midpoint of focus was located which indicated that the desired overall sharpness could be achieved in the photography by stopping down the lens aperture to f/11. There was not enough light, however, to permit motion picture photography at this aperture at conventional camera speeds. The alternative was to shoot the sequence in stop-motion, a frame at a time, at exposures of ½ minute each—which is the procedure decided upon. Secondly, the extreme wide-angle characteristic of the lens diminished images to such an extent that it was often necessary to move the camera within 2 or 3 inches of a 3-foot planet model in order to fill the frame with the subject. To get a realistic illusion of soaring past the Moon, the camera was dollied, between stop-motion exposures, to within 1/4-inch of the surface of the model. In the case of Saturn, the scene began with a conventional long shot of the ringed planet —then the camera approached and tilted 90 degrees, skimming along within 1/8-inch of the slowly revolving rings. | |

SEATTLE WORLD FAIR visitors view "Journey To The Stars"

projected overhead on dome-shaped screen. The 15-minute color film was

screened for more than 6,000 performances during 1962, was seen by an

audience estimated at 4½ million. SEATTLE WORLD FAIR visitors view "Journey To The Stars"

projected overhead on dome-shaped screen. The 15-minute color film was

screened for more than 6,000 performances during 1962, was seen by an

audience estimated at 4½ million.The lift-off from Earth which opens the picture might have been filmed with greater ease had a 10-foot globe been used with the camera mounted on a Chapman boom. Since elements of such size were not practical, the camera started at a point 1/8 of an inch from the surface of a 4-foot Earth model, skimmed along in simulated orbit and then lifted free of the planet —the entire maneuver taking approximately 25 seconds on the screen. A special cradle was built for the camera which incorporated two gear-heads, mounted one above the other. This permitted full 360-degree horizontal and 160-degree vertical rotation of the camera to simulate the view from the lookout port of a spaceship. Each gear-head was precisely calibrated to insure the smoothest possible stop-motion photography. As the camera approached within 18 inches of an object, focus became highly critical and had to be corrected every five or six frames. Precise control was made possible by a Vernier gauge having micrometer calibrations down to 1/1000th of an inch. Checking focus through the lens was a complicated operation, there being no lateral rackover mechanism on the camera. In order to make a quick check of the framing only, the camera was racked back from the lens and a prism-type viewer inserted sideways at the film plane to show an inverted image of the scene. To check for critical focus, however, it was necessary to clear the film, disengage it from the movement, remove the movement from the camera and insert a special scope inside the camera body for critical viewing through the lens. Phenomena such as the Beta Lyra star, with its spiral-shaped luminous trail, the Super Nova (an exploding star) and the Andromeda galaxy were created by means of multi-plane animation techniques using glass "eels" up to five feet square. The coloring for these heavenly objects was derived from authentic color photographs taken at Mt. Wilson Observatory. A dense celestial cloud of wispy gas—called Lagoon Nebula — was simulated by constructing a large wire tunnel, which was sprayed first with artificial cobwebs and then with prismatic colors of blue and red. It was built in breakaway sections so that the camera could move through it. | |

|

With filming now underway, facilities had to be adapted for processing

and printing. Because of the non-standard characteristics of the raw

stock it was necessary for Technicolor to modify its 70mm friction drive

positive machine to negative processing. Lin Dunn, Don Weed and William

Lüttschwager combined efforts to convert a Model J Bell & Howell

continuous printer to 70mm for the printing of dailies and release

prints. Special film-handling equipment, such as gang synchronizers, splicers, etc., was built by Benson-Lehner. It developed that optical printing would be necessary to superimpose the main images of the planets over the star backgrounds and to create other special effects. For this Film Effects of Hollywood designed and built a special optical printer. This incorporated a second Benson-Lehner camera set-up for bi-packing and a newly-built projection head. So that experimentation in the projection phase might continue during production, the complete dome and projection system were set up on Stage 10 of Hal Roach Studios, in Culver City, Calif., this being the only available building in Los Angeles having sufficient ceiling clearance to accommodate the installation. Two months before opening of the Fair the dome and equipment were dismantled and shipped to Seattle for installation. A sound system was incorporated, consisting of a four-track Ampex 35mm tape transport synchronized to the two projectors with a switching circuit to tie in to the particular projector in operation. The dome was suspended from the ceiling within the square building so that the axis had a 10-degree incline normal to the 10-degree slope of the tiered audience area within the auditorium. It was intended that the audience should stand during the showing, for which hand-rails were provided. The projection booth was elliptical in shape and centered to the dome. The projection lens extended from the booth at a height to provide a clear throw to the screen. Cinerama operated the exhibit during the entire run of the Fair using a crew of six projectionists in three shifts, and giving 33 continuous performances a day for 184 days without any down-time due to equipment malfunctions. Twenty release prints were used in over 6,000 performances for an average of 264 performances per print. Meanwhile, "Journey to the Stars" continues to thrill visitors to Seattle's Spacearium, which is now part of a permanent science exhibit established after the closure of the 1962 Fair. Reduced to 35mm format and projected on a 30-foot dome, the film recently played to more than 40,000 people at a space show presented by the Lytton Center of Visual Arts in Hollywood. It will also be a special attraction at the forthcoming Los Angeles Home Show. |

|

| Go: back - top - back issues - news index Updated 21-01-24 |